This year’s annual conference of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Amerikastudien (German Association for American Studies), which takes place June 12-15, 2014 in Würzburg, is devoted to the topic of “America after Nature” — a topic that in many ways (unfortunately) couldn’t be timelier. In this context, Ulfried Reichardt and Regina Schober (both of Universität Mannheim) have organized a workshop on “Nature, Technology, and the Body: Posthumanist Interfaces of the Networked Self,” in which I will be participating. Besides the topic, the form of the workshop is itself quite exciting, as it will consist not of paper presentations (“talks” in the conventional sense) but three roundtable discussions, prefaced only by brief presentations of several core thesis statements prepared by the participants. Here’s how the organizers explain their rationale:

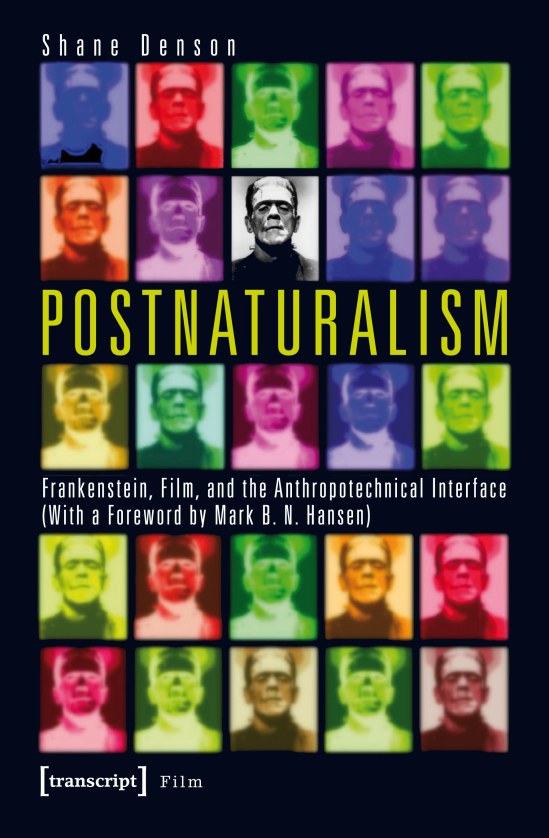

I will be participating in the first thematic cluster, “theoretical perspectives,” which I’ll be discussing with Hanjo Berressem (Cologne), Laura Bieger (Freiburg), Stefan Danter (Mannheim), and Wojciech Malecki (Wrocław). My own contribution, outlined in the three theses below, essentially tries to bring together the perspectives of my two forthcoming books: Postnaturalism (see the publisher’s preview here) and Post-Cinema (a collection that I am co-editing with Julia Leyda). These connections have been implicit in my work for quite a while, but this is the first time I’ve explicitly tried to articulate them as a central theoretical focus. Here is my thesis paper:

Post-Cinematic Interfaces with a Postnatural World – 3 Theses

Shane Denson

∀

1. Postnaturalism is the thesis that “we have never been natural” (and neither has nature, for that matter).

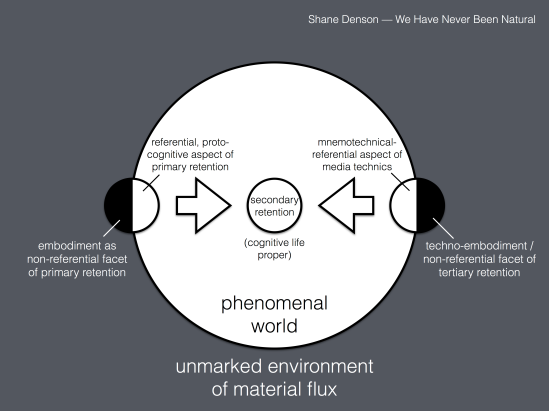

In response to debates over the alleged postmodernity of (Western) societies at the end of the twentieth century, Bruno Latour famously claimed that “we have never been modern.” Building upon Latour’s slogan and upping the ante, Donna Haraway has argued more radically that “we have never been human.” In other words, it’s not just in the age of prosthetics, implants, biotech, and “smart” computational devices that the integrity of the human breaks down, but already at the proverbial dawn of humankind – for the human has co-evolved with other organisms (like the dog, who domesticated the human just as much as the other way around). From an ecological as much as an ideological perspective, the human fails to describe anything like a stable, well-defined, or self-sufficient category. The postnatural thesis that “we have never been natural” doesn’t so much try to outdo Latour and Haraway as to refocus some of the themes that are inherent in these discussions and to deflect some of the attention away from the human (which the idea of posthumanism still paradoxically places in a central position). Human and nonhuman, natural and unnatural agencies are products of mediations and symbioses from the very start, I contend. In order to argue for these claims I take a broadly ecological view and focus not on discrete individuals but on what I call the “anthropotechnical interface” – the phenomenal and sub-phenomenal realm of mediation between human and technical agencies, where each impinges upon and defines the other in a broad space or ecology of material interaction. On this view, the notion of interfacing describes not just the narrow space of interaction between fully formed subjects and objects (e.g. a computer user, the mouse, the screen, etc.) but situates these transactions in a broader space of co-constitution. The anthropotechnical interface, accordingly, is a realm of diffuse materiality where centered or situated embodiment and phenomenality brush up against the unmarked environment, where technical mediation can be seen as a metabolic agency that works to reorganize the world (or nature) materially.

∃

2. Post-cinema is the notion that contemporary media are no longer accountable for in terms of perceptual interfaces alone.

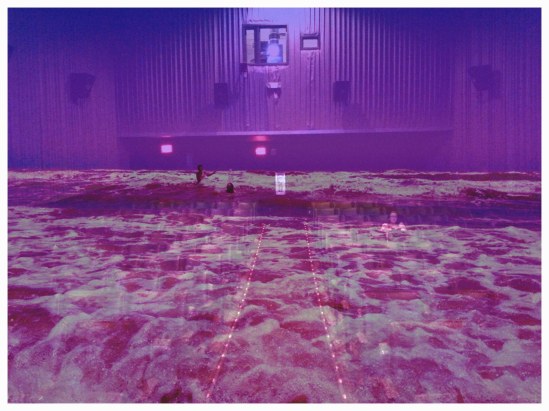

It is, of course, a simplification to suggest that the operation of media was ever confined to the perceptual register, i.e. the phenomenological level of interaction between subjects and objects; the point of postnaturalism, in this regard, is precisely to reveal a broader, sub-phenomenological register that has been implicated in media and mediation from the start, and to situate this register as the very substrate out of which subjects and objects are formed and transformed. It is nevertheless true that cinema, as the paradigmatic technical medium of the 20th century, served to concentrate an unprecedented amount of energy and focus on the mediation of specifically perceptual experience – to channel human vision (and hearing), to bundle psychic interest, and broadly to direct the focus of subjective intentionality. (In this sense, even psychoanalytic film theory, which emphasized unconscious mechanisms at work, still followed cinema’s perceptual-phenomenological bias when it theorized “suture” and similar positionings of the subject.) With the advent of computational media, however, the perceptual register loses its primacy of place, as the operation of media opens onto a broader space of non-phenomenological activity, of microtemporal and algorithmic functioning that is categorically beyond the purview of perception or subjective experience. With the shift from photochemical to digital processes, even moving-image media become less about the channeling of perspective than about the modulation of affect, as Steven Shaviro has argued in his work on “post-cinematic affect.” Accordingly, at the heart of the shift from a cinematic to a post-cinematic media regime is nothing less than a transformation of the anthropotechnical interface itself, as media’s access to the sub-phenomenological realm is expanded and operationalized as never before.

∞

3. Together, post-cinema and postnaturalism mutually inform one another and illuminate the (medial) parameters of interfacing in the contemporary world.

In accordance with the notion of the anthropotechnical interface, as it is articulated in a postnatural framework, media should be seen not only as empirical objects and systems, but as infra-empirical constraints and enablers of agency such that media may be described, following Mark B. N. Hansen, as the “environment for life” itself. Accordingly, media-technical innovation and change translates into ecological change, transforming the parameters of life in a way that outstrips our ability to think about or capture such change cognitively – for at stake in such change is the very infrastructural basis of cognition and subjective being. So postnaturalism, as a philosophy of media and mediation, tries to think about the conditions of anthropotechnical evolution, conceived as the process that links transformations in the realm of concrete, apparatic media (such as film and TV) with more global transformations at a quasi-transcendental level. Operating on both empirical and infra-empirical levels, media might be seen, on this view, as something like articulators of the phenomenal-noumenal interface itself. Importantly, though, this quasi-transcendental function of media is materially and ecologically immanent, very much a part of this world; both embedded within and structuring the environmental flows between formed and unformed materials, this ecological operation of media can be compared to that of metabolism. Post-cinema, marking a change in the medial infrastructure of life, can (and should) be viewed through the lens of postnaturalism as an environmental transformation that operates on the totality of metabolic exchange. At the same time, post-cinematic mediation, through its expanded access to and operationalization of the sub-phenomenological realm, grants us unprecedented (non-representational) access to this metabolic level. Postnaturalism therefore describes the general framework within which the specific transformations of post-cinema take place, while post-cinema offers a very special case for thinking about the sub-phenomenological materiality that has defined the interface of life from the start. Not only have we never been natural, but in an important sense, “we have never been cinematic” either.

Bibliography:

Denson, Shane. Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface. With a foreword by Mark B. N. Hansen. Bielefeld: Transcript, forthcoming 2014.

Denson, Shane and Julia Leyda, eds. Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film. Sussex: REFRAME Books, forthcoming 2014.

Hansen, Mark B. N. Embodying Technesis: Technology Beyond Writing. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2000.

___. Feed-Forward: On the Future of Twenty-First-Century Media. Chicago: U of Chicago P, forthcoming 2014.

___. “Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 23.2-3 (2006): 297-306.

___. New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

___. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993.

Shaviro, Steven. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zero Books, 2010.