What’s there to be afraid of anyway? The video above, which I repost here for Halloween, offers one sort of approach to this question by recontextualizing cinematic horror against a more diffuse sort of horror that emanates from a changing media environment.

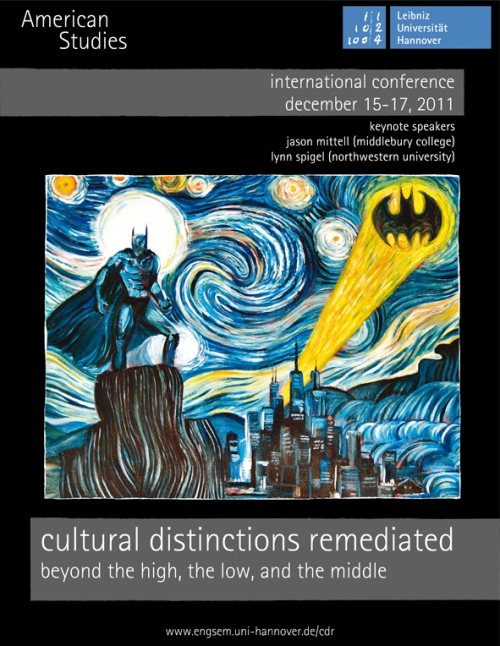

The video is a screencast of a talk I gave at the 2010 annual meeting of the American Studies Association: “Media Crisis, Serial Chains, and the Mediation of Change: Frankenstein on Film.” Thematizing transitional phenomena of media change and transformation, the paper itself occupies a transitional place between my dissertation, Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, and my current postdoctoral research on “Serial Figures and Media Change” (with Ruth Mayer, part of the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality–Aesthetics and Practice”).

The talk attempts to excavate a forgotten experiential dimension–an experience of crisis related to changes in the media landscape–that uncannily informs the iconic image of Frankenstein’s monster. The notion that media changes precipitate phenomenological crises, as I put forward here, is informed by Mark Hansen’s view that media define “the environment for life” (or, more generally, the environment for agency, as I propose in Postnaturalism). While media are embodied in discrete apparatic technologies, they are inseparable from the total milieu of agential capacities; media changes thus have both a local and a global dimension, and it is this global aspect (and the networked distribution of human and technical agencies that it signifies) that explains why media changes might occasion affective states of crisis, anxiety, the uncanny, or present themselves as just plain scary.

My talk is also informed by a variety of concerns that I share with people like Jussi Parikka, who along with Garnet Hertz has argued for a conception of “zombie media,” according to which media never simply die but continue to exert a haunting influence that can be appropriated for media-theoretical and artistic purposes. Their essay “Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method,” which Hertz and Parikka presented at the transmediale 2011 in Berlin, is introduced thus:

There is always a better camera, laptop, mobile phone on the horizon: new media always becomes old. We approach this phenomenon under the umbrella term of media archaeology and aim to extend the media archaeological interest of knowledge into an art methodology. Hence, media archaeology becomes not only a method for excavation of the repressed, the forgotten, the past, but extends itself into an artistic method close to Do-It-Yourself (DIY) culture, circuit bending, hardware hacking, and other exercises that are closely related to the political economy of information technology, as well as the environment. Media embodies memory, but not only human memory; memory of things, of objects, of chemicals, and circuits that are returned to nature, so to speak, after their cycle. But these can be resurrected. This embodiment of memory in things is what relates media archaeology to an ecosophic enterprise as well.

(Quoted from here at the transmediale website.) And here is a video of the complete talk:

In his “manifesto for digital spectrology,” Parikka expands on the ghostly side of all this, bringing the notion of hauntology into close connection with the materiality of media-technologies and the ecology of media evolution:

Digital Spectrology is that dirty work of a cultural theorist who wants to understand how power works in the age of circuitry. Power circulates not only in human spaces of cities, organic bodies or just plain things and objects. Increasingly, our archaeologies of the contemporary need to turn inside the machine, in order to illuminate what is the condition of existence of how we think, see, hear, remember and hallucinate in the age of software. This includes things discarded, abandoned, obsolete as much as the obscure object of desire still worthy of daylight. As such, digital archaeology deals with spectres too; but these ghosts are not only hallucinations of afterlife reached through the media of mediums, or telegraphics, signals from Mars, the screen as a window to the otherwordly; but in the electromagnetic sphere, dynamics of software, ubiquitous computing, clouds so transparent we are mistaken to think of them as soft. Media Archaeology shares a temporality of the dead and zombies with Hauntology. Dead media is never actually dead. So what is the method of a media archaeologist of technological ghosts? She opens up the hood, looks inside, figures out what are the processual technics of our politics and aesthetics: The Aesthetico-Technical.

– inspired by the work of MicroResearchlab – Berlin/London, the short text was written for Julian Konczak/Telenesia.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that the media-ecological horror of media change is always embedded in (and itself provides a material and affective context for) a political landscape in which technologies are harnessed for oppression, for the maintenance of unequal power distributions, and, of course, for profit. Here, then, are some real-life zombies from #OccupyWallStreet: