See also here and here, or contact Shane Denson for more info.

See also here and here, or contact Shane Denson for more info.

On the occasion of our “Chaos Cinema” film series, where the topic yesterday was Michael Bay’s Transformers (2007), I gave a short talk on the notion of “discorrelated images” — an idea that percolates (though is not named as such) in my dissertation, emerging through conversation with a number of thinkers, ideas, and images: Deleuze (and Guattari) on “affection images” and “faciality,” Henri Bergson on living (and other) “images,” Brian Massumi on affect and “passion,” Mark Hansen on the “digital facial image” and “the medium as environment for life,” and others, including Boris Karloff and the iconic image of Frankenstein’s monster. All of which are left out of the picture in yesterday’s talk — which was designed to set the stage for further thinking, to be suggestive rather than definitive, and thus serves more to raise questions than to answer them. In any case, I reproduce the text (and slides) here, in case anyone is interested:

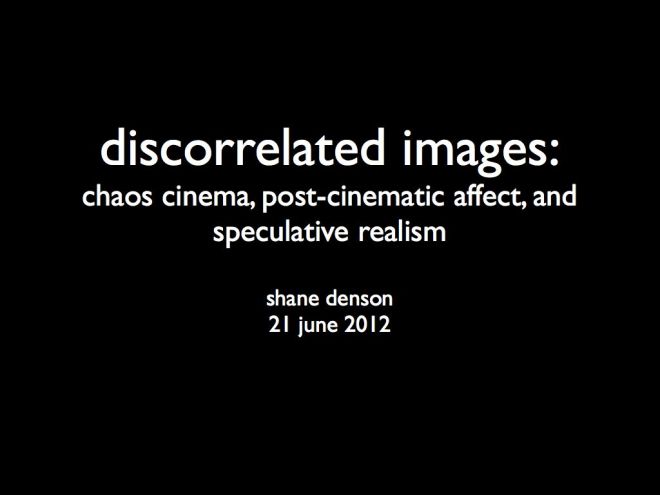

Michael Bay’s 2007 film Transformers can be seen as an interesting case of transmedial serialization in the context of what Henry Jenkins calls our “convergence culture” — interesting because, reversing the typical order of merchandising processes, Bay’s film and its sequels are part of a franchise that originates with (rather than giving rise to) a line of toys. Unlike Star Wars action figures, for example, which are extracted from narrative contexts and made available for supplementary play, Transformers are toys first, and only subsequently (though promptly) narrativized. These toys, first marketed in the US by Hasbro in 1984, but based on older Japanese toylines going by other names, spawned several comic-book series, Saturday-morning cartoons, an animated film, novelizations, video games implemented across a wide range of platforms, and the trilogy of films directed by Michael Bay with backing from Steven Spielberg.

Despite such rampant adaptation and narrativization, however, we shouldn’t lose sight of the toys, which continue to be marketed to kids today, nearly thirty years after they were first marketed to me and my elementary school friends: the toys themselves offer only the barest of narrative parameters (good guys vs. bad guys) for the generation of storified play scenarios. Transformers, in opposition to Star Wars figures, which always exist in some relation to preexistent stories, are not primarily interesting from a narrative point of view at all: Autobots and Decepticons are basically just two teams, and the play they generate need not be any more narratively complex than a soccer or football match (where tales are told, to be sure, but as a supplement to the ground rules and the moves made on their basis).

Instead, the basic attraction of Transformers is, as the name says, the operation of transformation. Transformers are therefore mechanisms first, and the attraction for children (mostly boys) growing up in the early 80s was to see how they worked. Transformers, in other words, are the perfect embodiments of an “operational aesthetic” in the original sense of the term, first introduced by Neil Harris to describe the attraction of P.T. Barnum’s showmanship against the background of nineteenth century freak shows, magic shows, World Expos, and popular exhibitions of the latest technologies. More recently, Jason Mittell has usefully employed the concept to explain the attraction of “narratively complex television,” but the operationality at issue here (i.e. in the case of the Transformers) is of a stubbornly non-narrative sort. Thus, consonant with a general trait of science-fiction film (with its narratively gratuitous displays of special effects, which often interrupt the story to show off the state of the art in visualization technologies), narrativizations of Transformers are inherently involved in competitions of interest: story vs. mechanism, diegesis vs. medium. The Transformers themselves, who are more interesting as mechanisms than as characters, are the crux of these alternations.

(On this basis we might say, riffing on Niklas Luhmann, that they embody an “operative difference between substrate and form” and thus themselves constitute the “media” of a flickering cross-medial serial proliferation. But that’s another story…)

Let me go back to the idea of convergence culture, which I’d like to connect with this operational mediality. It’s important to keep in mind that our convergence culture, in Jenkins’s terms, is enabled by a different type of convergence with which it remains in constant communication: viz. the specifically technological convergence of the digital. Is it stretching things to say that the original toys latched onto an early eight-bit era fascination with the way electronic machines could generate interactive play? In other words, they spoke to an interest in the way machines worked — as the basic object of interactive video games — and promoted fantasies of artificial intelligences and robotic agencies that would be a match for any human subject (or gamer).

In any case, Michael Bay’s Transformers, along with the film’s sequels, would not be possible without much more advanced digital technologies; the films know it, we know it, and the films know we know it, so the role of the digital is not hidden but foregrounded and positively flaunted in the films. Typically for a transitional era of media-technological change, which, it would seem, we are still going through with respect to the digitalization of cinema (and of life more broadly), there is a fascination with medial processes that the films hook into. The result is that attentions are split between diegesis and medium, story and spectacle. The Transformers serve as a convenient fulcrum point for such oscillations, thus capitalizing on the uncertain valencies of media change while connecting phenomenological dispersal with a story that in some ways speaks to a larger decentering of human perspectives and agencies in the face of convergence and computation processes — to a feeling of contingency about the human that is related in various ways to digital technologies.

For example, there’s a sense of powerlessness with respect to digitally automated finance, which employs robotically operating algorithms to expedite the process and efficiency of transactions, splitting major operations into distributed micro-scale packet transfers that occur faster than the blink of an eye, and at truly sublime scales — both infinitesimally smaller and faster than human sensory ratios and with the potential to produce cataclysmically large results. The entire realm of human action, which exists in between these scales, is marginal at best: the machines originally meant to serve the interests of (some) humans end up serving only the algorithms of a source code — with respect to which, we are perhaps only bugs in the system. It is easy to extrapolate sci-fi fantasies: for example, the emergence of Skynet — or is it Stuxnet?

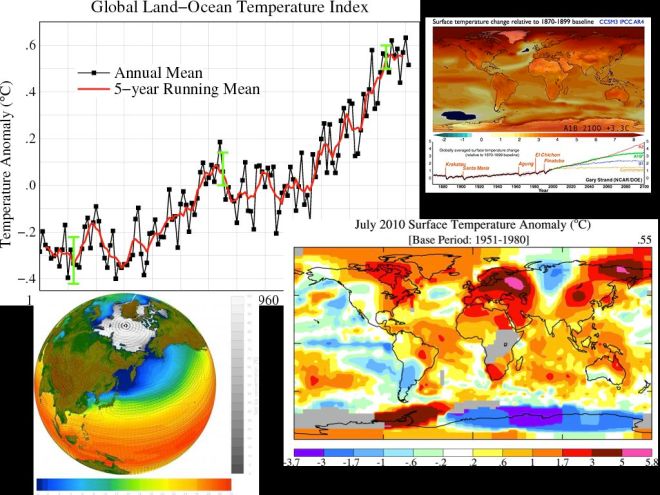

But the decentering of the human perspective through digital technology is taking place in much less fantastic manners, and in ways that do not support any kind of humans-first narratives of heroic reassertion: global warming, which is revealed to us through digital modeling simulations, points not towards our roles as victims of a pernicious technology of automation, but shows us to be the culprits in a crime the scale of which we cannot even begin to imagine. Categorically: we cannot imagine the scale, and this fact challenges us to rethink our notions of morality in ways that would at least attempt to account for all the agencies and ways of being that fall outside of narrowly human sense ratios, discourses, cultural constructions, senses of right and wrong, the true and the beautiful, the false and the ugly…. Through digital technologies, we have found ourselves in an impossible position: our technologies seem to want to live and act without us, and our world itself, ecologically speaking, would apparently be far better off without us. We are forced, in short, to try to think the world without us.

“Without us” can mean both “in our absence” or “beyond us” — outside our specific concerns, attachments, and modes of engagement with the world. The attempt to think, in this sense, “the world without us” characterizes the goal of “speculative realism,” a recent tendency in philosophy defined by its opposition to what Quentin Meillassoux calls “correlationism,” or the idea that reality is exhausted by our means of access to it. Against this notion, which correlates human thought and being on a metaphysical level, the speculative realists challenge us to think the world apart from our narrow view of it, to renounce an essentialism of the human perspective, and to escape to the “Great Outdoors.”

What does this have to do with Transformers and so-called “chaos cinema”? I’m trying to suggest something about the affective state, the structure of feeling, that produces and is (re)produced in and by our media culture today — a structure of feeling that Steven Shaviro calls “post-cinematic affect.” This broader context is largely ignored in Matthias Stork’s conception of “chaos cinema,” which is defined narrowly and technically, in terms of a break with classical continuity. These breaks do occur, and Stork has demonstrated their existence quite powerfully in his video essays, but they are only symptomatic of larger shifts. Shaviro has put forward a seemingly related notion of “post-continuity,” but he is careful to point out that continuity is not what’s centrally at stake. Post-cinematic affect is not served or expressed solely by breaking with principles of continuity editing; rather, continuity is in many instances simply beside the point in relation to a visceral awareness and communication of the affective quality of our historical moment of indeterminacy, contingency, and radical revision. The larger significance of a break with principles of classical continuity editing — rather than just sloppy filmmaking, as Stork sometimes seems to suggest, or quasi avant-garde radicalism — has instead to do with the correlation of continuity principles with the scales and ratios of human perception. Suture and engrossment in classical Hollywood works because those films structure themselves largely in accordance with the ways that a human being sees the world. (It goes without saying that this perceptual model is one that has as its touchstone a normative model of human embodiment, neurotypical cognitive functioning, and relatively unmarked racial, class, and gender types.) And while it has long been clear to feminist critics, among others, that the normative model of (unqualified, unmarked) humanity to which classical film speaks was in need of problematization, I would argue that the human itself has become a problem for us, and that “our” films have registered this in a variety of ways. The momentary breaks with continuity that Stork singles out as the defining features of chaos cinema are just one of the ways.

More generally, I suggest, we witness the rise of the discorrelated image: an image that problematizes, if not altogether escaping, the correlation of human thought and being. The teaser trailer for Transformers (also integrated into the film itself) uses nonhuman subjective shots — images seen through the eyes of a robot, the Mars rover Beagle 2 — to promote its story about an intelligent race of machines. In a somewhat different vein, The Hurt Locker opens with images mediated through the camera-eyes of a robot employed for defusing bombs from a distance. The Paranormal Activity series employs a variety of robotic or automated camera systems. Wall-E, Cars, and a host of other digital animation films are all about the perceptions, feelings, and affects of nonhuman machines. Of course, there’s nothing new about such representations, and they are highly anthropomorphic besides. But what if these are just primers, symptomatic indicators, or gentle nudges, perhaps, towards something else? (Significantly, both Jane Bennett, in the context of her notion of “vibrant matter,” and Ian Bogost, with regard to his project of “alien phenomenology,” have argued for the necessity of a “strategic anthropomorphism” in the service of a nonhuman turn.) In fact, what we find here is that the representational level in such films is coupled with, and points toward, an extra-diegetic fact about the films’ medial mode of existence: digital-era films, heavy with CGI and other computational artifacts, are themselves the products of radically nonhuman machines — machines that, unlike the movie camera, do not even share the common ground of optics with our eyes. Accordingly, the supposed “chaos” of “chaos cinema” is not about a break with continuity; rather, it’s about a break with human perception that materially conditions the cinema (and visual culture more broadly) of the early 21st century. Again, in Transformers, the process of transformation is the crux, the site where discorrelation is most prominently at stake as the object of an operational aesthetic. The spectacle of a Transformer transforming splits our attention between the story and its (digital) execution, between the diegesis and the medial conditions of its staging, which are in turn folded back into the diegesis so as to enhance and distribute a more general feeling of fascination or awe.

What do we see when a Transformer transforms? What we don’t see, necessarily, is a break with the principles of continuity editing. Instead, we witness a discorrelation of the image by other means: we register the way in which our desire to trace the operation of the machine is categorically outstripped by the technology of digital compositing, which animates the transformation by means of algorithmic processes operating on the scale of a micro-temporality that is infinitesimally smaller and faster than any human subject’s ability to process or even imagine it. These images, I contend, are the raison d’etre of the film itself. But they are not “for us,” except in the sense that they challenge us to think our contingency, to intuit or feel that contingency on the basis of our sensory inadequacy to the technical conditions of our environments. A hopeful story, complete with adolescent love interest and other minor concerns, counters this vision of our own obsolescence. But the discorrelated image of transformation is the aesthetic crux of the film, quite possibly the only thing worth watching it for, and perhaps even the bearer of a (probably unintentional) ethical injunction, beyond the rather flimsy human-centered narrative (and the clearly conservative politics, militarism, and apparent misogynism): the discorrelated image, in which the process of transformation can only be suggested to our lagging sensory apparatuses, challenges us performatively, by confronting us with an image of our own discorrelation; viscerally, it asks us to attune ourselves to an environment that is broader than our visual capture of it, faster than our ability to register it, and more or less indifferent to our concernful perception of it. Materially, medially, and ontologically true to the 1980s tagline, the discorrelated images of Michael Bay’s Transformers are indeed “More than meets the eye!”

On the occasion of his visit to the Leibniz University of Hannover, the American Studies department / English Seminar and the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research are proud to present a series of lectures and workshops with renowned media theorist Mark Hansen.

Professor of Literature at Duke University since 2008, Mark Hansen is the author of the monographs Bodies in Code: Interfaces with Digital Media (2006), New Philosophy for New Media (2004), and Embodying Technesis: Technology Beyond Writing (2000), as well as numerous other publications in the field of media theory. In addition to two guest lectures, a workshop will provide the opportunity to discuss Prof. Hansen’s research on the basis of selected texts.

Mon, 2 July 2012, 6:00 pm: Lecture: “Feed Forward, or the ‘Future’ of 21st Century Media”

Tue, 3 July 2012, 10:00 am: Guest lecture: “The End of Pharmacology?: Historicizing 21st Century Media.”

Fri, 6 July 2012, 2:00 – 5:00 pm: Workshop on selected media-theoretical texts by Mark Hansen (to participate in the workshop, please register via email)

(All events will take place in room 615 in the “Conti-Hochhaus”: building 1502 at Königsworther Platz 1.) For further information and to register for the workshop, please contact Shane Denson.

10,000: As of today, the number of page views on this blog since its inception in May 2011.

Today, sometime between 1:00 and 3:30 p.m., this blog had its 10,000th page view, when a visitor from either Spain, Canada, or Germany (in which case it was very possibly my wife) clicked on this site, either deliberately or (as I’m told happens occasionally on the interwebs) by chance.

Admittedly, 10,000 hits over the course of 11 months is not a whole lot in comparison with the kind of traffic that corporate sites, media outlets, universities, or even some of the more popular academic bloggers get, but it’s nevertheless not an altogether insignificant milestone for a fledgling media initiative at a German university posting largely on local events, niche-interest topics like seriality or posthumanism, or whatever happens to interest me at the time.

I thought I’d take the opportunity, therefore, to review and take stock of things. Luckily, WordPress provides a range of interesting statistics that are perfect for this kind of occasion.

To start with, 122 posts (this one included) have been made since I set up the blog on May 5, 2011. There were only 2 visitors to the blog that May (I didn’t go public with the blog until June, so who knows what led those two poor souls here then), roughly 200 hits in June, and since November 2011 the blog’s been averaging about 1500 monthly page views.

The five most popular pages have been: 1. the main landing page (4,668 hits), 2. Conference Program: “Cultural Distinctions Remediated” (detailing the conference we held here in December 2011; 366 hits), 3. the About page (235 hits), 4. Bollywood Nation (our film series in the winter semester 2011/2012; 188 hits), and 5. Bollywood Nation: Background / Context (likewise 188 hits).

Most people arrive here by way of a search engine (4,260 referrals total, including 3,329 from Google Image Search, 838 from “normal” Google searches, 28 from Bing, and a handful of others). There have also been 485 referrals from Facebook, 279 from Twitter, 259 from the English department at the Leibniz Universität Hannover, 93 from Jason Mittell’s blog Just TV, 93 from the homepage of the Popular Seriality research group, and lately an increasing number of referrals from Jussi Parikka’s Machinology blog, Steven Shaviro’s The Pinocchio Theory, Dylan Trigg’s Side Effects, and Bernard Dionysus Geogehan’s homepage.

Lately we’ve seen more and more people landing here deliberately (as evidenced by these referrals and the increasing number of people searching for terms like “medieninitiative hannover” or “denson postnaturalism”), but the list of top search terms evidences a mixed audience of intentional and accidental readers. The all-time top five search terms are: 1. television, 2. cheezburger

And finally, WordPress has recently started providing statistics on the countries where the blog’s visitors (or at least their IP addresses) are located. Statistics are only available since February 25, but since then the top five countries have been: 1. United States (454 hits), 2. Germany (437), 3. United Kingdom and Canada (tied at 177 each), 4. India (103), and 5. Australia (69).

So that’s where we’ve been, but where is the blog heading? What does the future hold? To be sure, only time will tell, but a number of things are in the works right now: the Media Initiative continues to develop, and a number of media-related events are being planned in Hannover (and elsewhere), so be on the lookout, and consider subscribing to the blog via e-mail (you can sign up on the right), an RSS reader of your choice, or your WordPress account, for example. Additionally, spread the word via your favorite social network, blog, or other modern mode of communicative being. And if that’s not enough, don’t forget: we’ve got plenty of cheezburgers, traffic, and metabolism for all your spambots!

(click on image for larger view)

“During the first decade of the 21st century, film style changed profoundly.”

This, at least, is the thesis put forward by Matthias Stork in a series of highly controversial video essays that have circulated recently on the Internet. According to Stork, “Contemporary blockbusters, particularly action movies, trade visual intelligibility for sensory overload, and the result is a film style marked by excess, exaggeration and overindulgence: chaos cinema.”

In a series of film screenings, we would like to engage critically with Stork’s notion of chaos cinema. We shall begin by viewing Stork’s video essays themselves, before moving on to some of the films he discusses and others that exemplify and/or challenge the paradigm of chaos cinema.

For those interested, here are some links to useful background and discussion:

First, Stork’s thesis must be seen against the background of David Bordwell’s notion of “intensified continuity,” which is seen to mark a change from the classical Hollywood style that dominated American cinema from around 1920 until (at least) the 1960s. Chaos cinema, according to Stork, goes further in effecting a radical break with continuity principles, whether classical or intensified.

Another important context is Steven Shaviro’s book Post-Cinematic Affect, which introduced the term “post-continuity.” (A Google Books preview can be found here, but note that approximately two-thirds of the book appeared in the open access journal Film-Philosophy under the title “Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales“.) More recently, Shaviro has returned to the topic and reflected explicitly on Stork’s notion of chaos cinema in a talk given at the 2012 annual conference of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, reprinted in full on his blog The Pinocchio Theory.

And here, finally, is the schedule of screenings (note that all screenings will be held in room 615 of the Conti-Hochhaus, at 6:00 pm):

April 26, 2012: “Chaos Cinema” (Matthias Stork, 2011)

May 24, 2012: Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000)

June 21, 2012: Transformers (Michael Bay, 2007)

July 5, 2012: Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (Edgar Wright, 2010)

July 19, 2012: WALL-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008)

Films will be shown in English original with subtitles where available. Screenings are open to all, so feel free to spread the word!

On Thursday, January 26, 2012, we will be screening the fifth and final film in our Bollywood Nation series: Chak De! India [Come on! India] (and not, as previously announced, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham…). As usual, the screening will begin at 6:00 PM (room 615 in the Conti-Hochhaus). More information about the film can be found on imdb.com.

On Thursday, January 5, 2012, we will be screening the fourth film in our Bollywood Nation series: Mr. and Mrs. Iyer. As usual, the screening will begin at 6:00 PM (room 615 in the Conti-Hochhaus). As indicated on our poster above, the 2002 film serves in several respects as a contrast to the other films in our series. More information about the film can be found on imdb.com.

The Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research and Jatin Wagle (in conjunction with his seminar “Long-Distance Hindu Nationalism and the Changing Figure of the Expatriate Indian in Contemporary Bollywood Cinema”) are proud to present a series of screenings this winter semester:

Bollywood Nation

From the first silent feature made in 1913, one of the many appeals of commercial Hindi cinema has been its persistent and multifarious staging of the Indian nationalism. It has been argued that the Bombay film constitutes a significant site for the popular negotiation of the Indian nation and that its history could even be told as an eccentric allegory of the checkered, postcolonial career of the Indian nation-state. In the 1960s and 1970s, for instance, when the “brain drain” paradigm ruled the official and dominant view of emigration in India, in the Hindi films the emigrant was portrayed as a sort of deficient Indian. His Indianness corrupted by Western decadence, he was someone who needed to be reformed, if not reviled. But, all this changed after the processes of economic liberalization were set in motion in 1991 and the Indian state started wooing the non-resident Indian (NRI). The new Bollywood NRI is not just an exemplary Indian, but even excessively so. In other words, he is more Indian than Indian, because he is both ultramodern and hypertraditional; he has a hugely successful career in the West, but his home is still an improbable oasis of Indian values and religiosity. Thus, the new Bollywood NRI embodies a deterritorialized cultural nationalism which utilizes the rhetoric of India’s alleged emergence as a global superpower. But, with the unprecedented global recognition and popularity of Bollywood, the rise of the new NRI has also been accompanied by an upsurge of Hindu nationalism within India and in the Indian diaspora. Does the changed socio-economic context and cinematic form account for Bollywood’s growing global appeal?

We plan to engage with these and other related issues in our series “Bollywood Nation” with five films to be screened between 27.10.2011 and 26.01.2012 at 18:00 in room no. 615.

27.10.2011 – Swades: We, the People [Homeland] (Dir. Ashutosh Gowariker, 2004, 187 mins.): A late renegotiation of the “brain drain” paradigm and could serve as a contrast to the new global NRI films. (more here)

24.11.2011 – Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge [The Big Hearted Will Take the Bride] (Dir. Aditya Chopra, 1995, 192 mins.): First successful new global NRI film, considered a classic of its kind. (more here)

08.12.2011 – Pardes [Foreign Land] (Dir. Subhash Ghai, 1997, 195 mins.): Another commercial success, both in India and abroad.

05.01.2012 – Mr. and Mrs. Iyer (Dir. Aparna Sen, 2002, 120 mins.): An English language, Indian film and not a Bollywood production; offers a contrasting aesthetic and another kind of negotiation with the composite idea of the Indian nation.

26.01.2012 – Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham… [Sometimes Happiness, Sometimes Sadness] (Dir. Karan Johar 2001, 210 mins.): One of the biggest commercial hits outside of India and the first Bollywood film to be released simultaneously in Germany, under the title In guten wie in schweren Tagen.

Es gibt viele Möglichkeiten, über die Initiative für interdisziplinäre Medienforschung informiert zu bleiben. Sie können unsere Google-Kalender (http://medieninitiative.wordpress.com/calendar/) abonnieren: XML, iCal,HTML, um auf dem Laufenden über medienrelevante Events und Aktivitäten der Initiative zu bleiben. Außerdem gibt es ein RSS feed für diesen Blog sowie die Möglichkeit, neue Posts per E-Mail zu abonnieren (“Email Subscription” rechts). Und nun können Sie uns auch auf Twitter folgen: http://twitter.com/#!/medieninitiativ!

Auf der rechten Seite gibt es eine automatisch aktualisierte Liste von “Upcoming Events,” die für die Medieninitiative oder für Medieninteressierten im Allgemeinen relevant sind. Gerne nehmen wir Events (Vorträge, Tagungen, CFPs, Ausstellungen, Vorführungen usw.) in unserem Kalender auf. Kontaktadresse finden Sie auf unsere “About”-Seite (oben).