As I recently announced, I was invited to give the keynote address at the 17th annual Texas State University Philosophy Symposium. Here, now, is the full text of my talk:

Philosophy of Science De-Naturalized: Notes towards a Postnatural Philosophy of Media

Shane Denson

The title of my talk contains several oddities (and perhaps not a few extravagances), so I’ll start by looking at these one by one. First (or last) of all, “philosophy of media” is likely to sound unusual in an American context, but it denotes an emerging field of inquiry in Europe, where a small handful of people have started referring to themselves as philosophers of media, and where there is even a limited amount of institutional recognition of such appellations. In Germany, for example, Lorenz Engell has held the chair of media philosophy at the Bauhaus University in Weimar since 2001. He lists as one of his research interests “film and television as philosophical apparatuses and agencies” – which, whatever that might mean, clearly signals something very different from anything that might conventionally be treated under the heading of “media studies” in the US. On this European model, media philosophy is related to the more familiar “philosophy of film,” but it typically broadens the scope of what might be thought of as media (following provocations from thinkers like Niklas Luhmann, who treated everything from film and television to money, acoustics, meaning, art, time, and space as media). More to the point, media philosophy aims to think more generally about media as a philosophical topic, and not as mere carriers for philosophical themes and representations – which means going beyond empirical determinations of media and beyond concentrations on media “contents” in order to think about ontological and epistemological issues raised by media themselves. Often, these discussions channel the philosophy of science and of technology, and this strategy will indeed build the bridge in my own talk between the predominantly European idea of “media philosophy” and the context of Anglo-American philosophy.

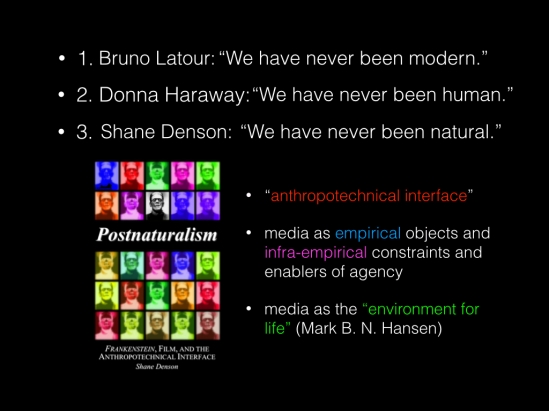

OK, but if the idea of a philosophy of media isn’t weird enough, I’ve added this weird epithet: “postnatural.” The meaning of this term is really the crux of my talk, but I’m only going to offer a few “notes towards” a postnatural theory, as it’s also the crux of a big, unwieldy book that I have coming out later this year, in which I devote some 400 pages to explaining and exploring the idea of postnaturalism. As a first approach, though, I can describe the general trajectory through a series of three heuristic (if oversimplifying) slogans.

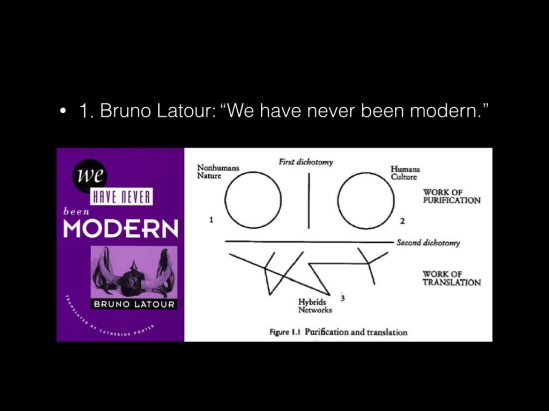

First, in response to debates over the alleged postmodernity of (Western) societies at the end of the twentieth century, French sociologist and science studies pioneer Bruno Latour, most famous for his association with so-called actor-network theory, claimed in his 1991 book of the same title that “We have never been modern.” What he meant, centrally, was that the division of nature and culture, nonhuman and human, that had structured the idea of modernity (and of scientific progress), could not only be seen crumbling in contemporary phenomena such as global warming and biotechnology – humanly created phenomena that become forces of nature in their own right – but that the division was in fact an illusion all along. We have never been modern, accordingly, because modern scientific instruments like the air pump, for example, were simultaneously natural, social, and discursive phenomena. The idea of modernity, according to Latour, depends upon acts of purification that reinforce the nature/culture divide, but an array of hybrids constantly mix these realms. In terms of a philosophy of media, one of the most important conceptual contributions made by Latour in this context is the distinction between “intermediaries” and “mediators.” The former are seen as neutral carriers of information and intentionalities: instruments that expand the cognitive and practical reach of humans in the natural world while leaving the essence of the human untouched. Mediators, on the other hand, are seen to decenter subjectivities and to unsettle the human/nonhuman divide itself as they participate in an uncertain negotiation of these boundaries.

The NRA, with their slogan “guns don’t kill people, people kill people,” would have us believe that handguns are mere intermediaries, neutral tools for good or evil; Latour, on the other hand, argues that the handgun, as a non-neutral mediator, transforms the very agency of the human who wields it. That person takes up a very different sort of comportment towards the world, and the transformation is at once social, discursive, phenomenological, and material in nature.

With Donna Haraway, we could say that the human + handgun configuration describes something on the order of a cyborg, neither purely human nor nonhuman. And Haraway, building on Latour’s “we have never been modern,” ups the ante and provides us with the second slogan: “We have never been human.” In other words, it’s not just in the age of prosthetics, implants, biotech, and “smart” computational devices that the integrity of the human breaks down, but already at the proverbial dawn of humankind – for the human has co-evolved with other organisms (like the dog, who domesticated the human just as much as the other way around). From an ecological as much as an ideological perspective, the human fails to describe anything like a stable, well-defined, or self-sufficient category.

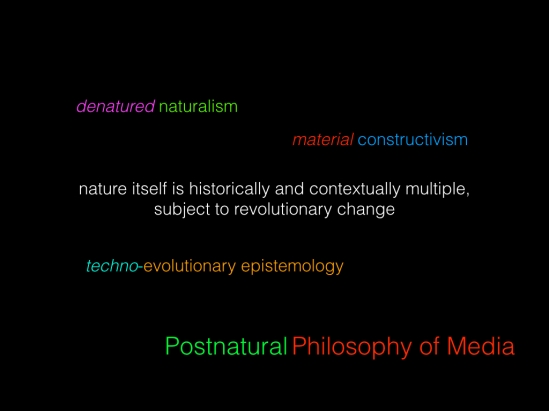

Now the third slogan, which is my own, doesn’t so much try to outdo Latour and Haraway as to refocus some of the themes that are inherent in these discussions. Postnaturalism, in a nutshell, is the idea not that we are now living beyond nature, whatever that might mean, but that “we have never been natural” (and neither has nature, for that matter). Human and nonhuman, natural and unnatural agencies are products of mediations and symbioses from the very start, I contend. In order to argue for these claims I take a broadly ecological view and focus not on discrete individuals but on what I call the anthropotechnical interface (the phenomenal and sub-phenomenal realm of mediation between human and technical agencies, where each impinges upon and defines the other in a broad space or ecology of material interaction). This view, which I develop at length in my book, allows us to see media not only as empirical objects, but as infra-empirical constraints and enablers of agency such that media may be described, following Mark Hansen, as the “environment for life” itself. Accordingly, media-technical innovation translates into ecological change, transforming the parameters of life in a way that outstrips our ability to think about or capture such change cognitively – for at stake in such change is the very infrastructural basis of cognition and subjective being. So postnaturalism, as a philosophy of media and mediation, tries to think about the conditions of anthropotechnical evolution, conceived as the process that links transformations in the realm of concrete, apparatic media (such as film and TV) with more global transformations at a quasi-transcendental level. Operating on both empirical and infra-empirical levels, media might be seen, on this view, as something like articulators of the phenomenal-noumenal interface itself.

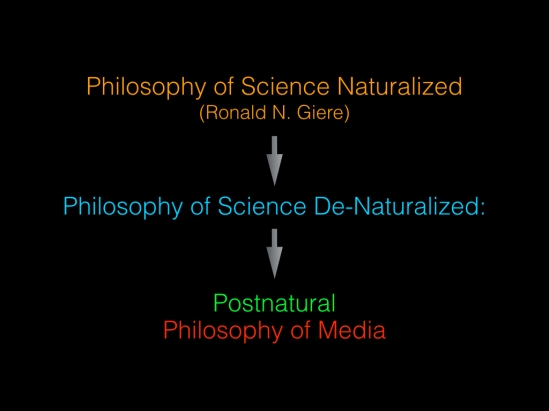

So the more I unpack this thing, the weirder it gets, right? Well, let me approach it from a different angle. Here’s where the first part of my title comes into play: “Philosophy of Science De-Naturalized.” Now, I mentioned before that postnaturalism does not postulate that we are living “after” nature; what I want to emphasize now is that it also remains largely continuous with naturalism, conceived broadly as the idea that the cosmos is governed by material principles which are the object, in turn, of natural science. And, more to the point, the first step in the derivation of a properly postnatural theory, which never breaks with the idea of a materially evolving nature, is to work through a naturalized epistemology, in the sense famously articulated by Willard V. O. Quine, but to locate within it the problematic role of technological mediation. By proceeding in this manner, I want to avoid the impression that a postnatural theory is based on a merely discursive “deconstruction” of nature as a concept. Against the general thrust of broadly postmodernist philosophies, which might show that our ideas of nature and its opposites are incoherent, mine is meant to be a thoroughly materialist account of mediation as a transformative force. So the “Philosophy of Science De-Naturalized,” as I put it here, marks a particular trajectory that takes off from what Ronald Giere has called “Philosophy of Science Naturalized” and works its way towards a properly postnatural philosophy of media.

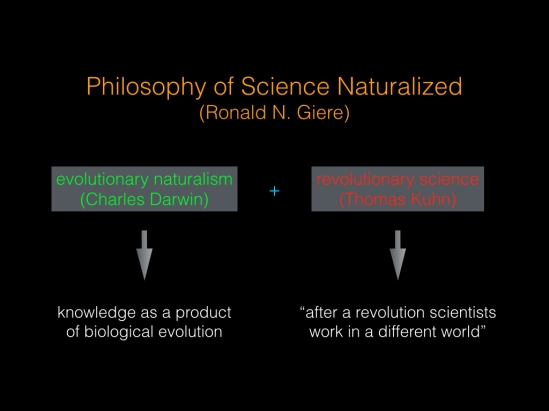

Giere’s naturalized philosophy of science is of interest to me because it aims to coordinate evolutionary naturalism (in the sense of Darwin) with revolutionary science (in the sense of Thomas Kuhn). In other words, it aims to reconcile the materialism of naturalized epistemology with the possibility of radical transformation, which Kuhn sees taking place with scientific paradigm shifts, and which I want to attribute to media-technical changes. Taking empirical science as its model, and taking it seriously as an engagement with a mind-independent reality, an “evolutionary epistemology” posits a strong, causal link between the material world and our beliefs about it, seeing knowledge as the product of our biological evolution. Knowledge (and, at the limit, science) is accordingly both instrumental or praxis-oriented and firmly anchored in “the real world.” As a means of survival, it is inherently instrumental, but in order for this instrumentality to be effective – and/or as the simplest explanation of such effectivity – the majority of our beliefs must actually correspond to the reality of which they form part. But, according to Kuhn’s view of paradigm shifts, “after a revolution scientists work in a different world” (Structure of Scientific Revolutions 135). This implies a strong incommensurability thesis that, according to critics like Donald Davidson, falls into the trap of idealism, along with its attendant consequences; i.e. if paradigms structure our experience, revolution implies radical relativism or else skepticism. So how can revolutionary transformation be squared with the evolutionary perspective?

Convinced that it contains important cues for a theory of media qua anthropotechnical interfacing, I would like to look at Giere’s answer in some detail. Asserting that “[h]uman perceptual and other cognitive capacities have evolved along with human bodies” (384), Giere’s is a starkly biology-based naturalism. Evolutionary theory posits mind-independent matter as the source of a matter-dependent mind, and unless epistemologists follow suit, according to Giere, they remain open to global arguments from theory underdetermination and phenomenal equivalence: since the world would appear the same to us whether it were really made of matter or of mind-stuff, how do we know that idealism is not correct? And because idealism contradicts the materialist bias of physical science, how do we know that scientific knowledge is sound? According to Giere, we can confidently ignore these questions once the philosophy of science has itself opted for a scientific worldview. Of course, the skeptic will counter that naturalism’s methodologically self-reflexive relation to empirical science renders its argumentation circular at root, but Giere turns the tables on skeptical challenges, arguing that they are “equally question-begging” (385). Given the compelling explanatory power and track record of modern science and evolutionary biology in particular, it is merely a feigned doubt that would question the thesis that “our capacities for operating in the world are highly adapted to that world” (385); knowledge of the world is necessary for the survival of complex biological organisms such as we are. But because this is essentially a transcendental argument, it does not break the circle in which the skeptic sees the naturalist moving; instead, it asserts that circularity is an inescapable consequence of our place in nature. In large part, this is because “we possess built-in mechanisms for quite direct interaction with aspects of our environment. The operations of these mechanisms largely bypass our conscious experience and linguistic or conceptual abilities” (385).

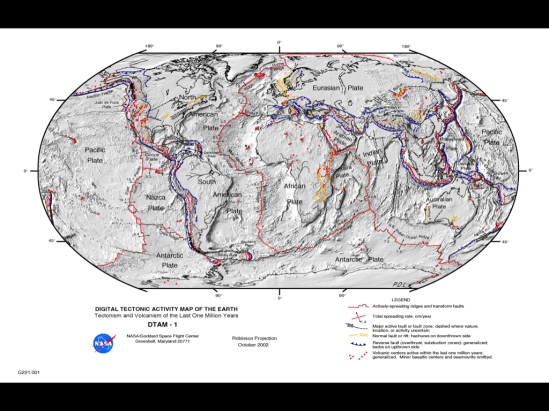

So much for the evolutionary perspective, but where does revolutionary science fit into the picture? To answer this question, Giere turns to the case of the geophysical revolution of the 1960s, when a long established model of the earth as a once much warmer body that had cooled and contracted, leaving the oceans and continents more or less fixed in their present positions, was rapidly overturned by the continental drift model that set the stage for the now prevalent plate tectonics theory (391-94). The matching coastlines of Africa and South America had long suggested the possibility of movement, and drift models had been developed in the early twentieth century but were left, by and large, unpursued; it was not just academic protectionism that preserved the old model but a lack of hard evidence capable of challenging accepted wisdom – accepted because it “worked” well enough to explain a large range of phenomena.

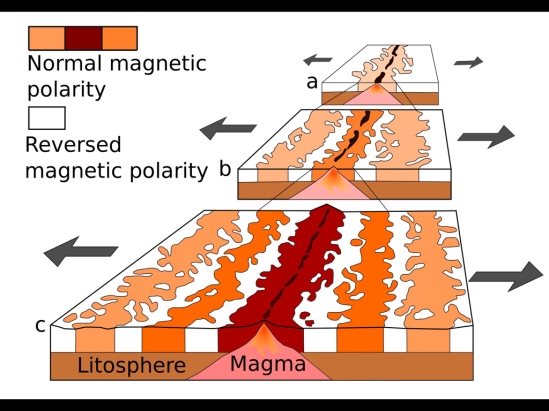

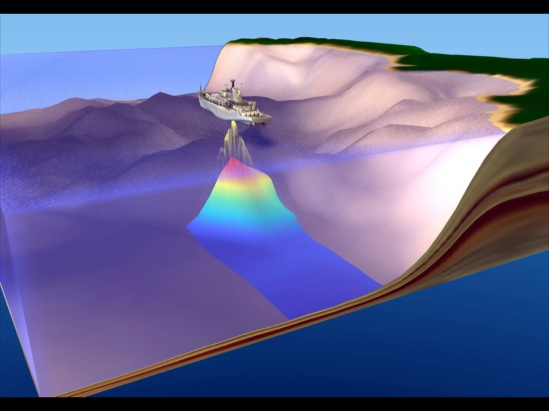

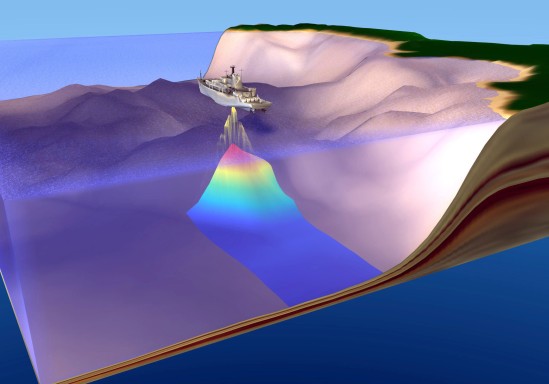

The discovery in the 1950s of north-south ocean ridges suggested, however, a plausible mechanism for continental drift: if the ridges were formed, as Harry Hess suggested, by volcanism, then “sea floor spreading” should be the result, and the continents would be gradually pushed apart by its action. The discovery, also in the 1950s, of large-scale magnetic field reversals provided the model with empirically testable consequences (the Vine-Matthews-Morley hypothesis): if the field reversals were indeed global and if the sea floor was spreading, then irregularly patterned stripes running parallel to the ridges should match the patterns observed in geological formations on land. Until this prediction was corroborated, there was still little impetus to overthrow the dominant theory, but magnetic soundings of the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge in 1966, along with sea-floor core samples, revealed the expected polarity patterns and led, within the space of a year, to a near complete acceptance of drift hypotheses among earth scientists.

According to Giere, naturalism can avoid idealistic talk of researchers living “in different worlds” and explain the sudden revolution in geology by appealing only to a few very plausible assumptions about human psychology and social interaction – assumptions that are fully compatible with physicalism. These concern what he calls the “payoff matrix” for accepting one of the competing theories (393). Abandoning a pet theory is seldom satisfying, and the rejection of a widely held model is likely to upset many researchers, revealing their previous work as no longer relevant. Resistance to change is all too easily explained. However, humans also take satisfaction in being right, and scientists hope to be objectively right about those aspects of the world they investigate. This interest, as Giere points out, does not have to be considered “an intrinsic positive value” among scientists, for it is tempered by psychosocial considerations (393) such as the fear of being ostracized and the promise of rewards. The geo-theoretical options became clear – or emerged as vital rather than merely logical alternatives – with the articulation of a drift model with clearly testable consequences. We may surmise that researchers began weighing their options at this time, though it is not necessary to consider this a transparently conscious act of deliberation. What was essential was the wide agreement among researchers that the predictions regarding magnetic profiles, if verified, would be extremely difficult to square with a static earth model and compellingly simple to explain if drift really occurred. Sharing this basic assumption, the choice was easy when the relevant data came in (394).

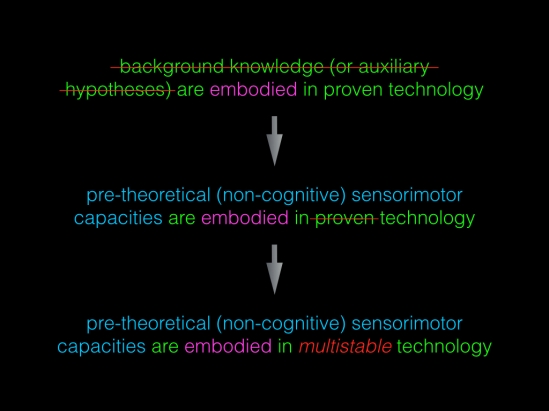

But the really interesting thing about this case, in my opinion, is the central role that technology played in structuring theoretical options and forcing a decision, which Giere notes but only in passing. The developing model first became truly relevant through the availability of technologies capable of confirming its predictions: technologies for conducting magnetic soundings of the ocean floor and for retrieving core samples from the deep. Indeed, the Vine-Matthews-Morley hypothesis depended on technology not only for its verification, but for its initial formulation as well: ocean ridges could not have been discovered without instruments capable of sounding the ocean floor, and the discovery of magnetic field reversals depended on a similarly advanced technological infrastructure. A reliance on mediating technologies is central to the practice of science, and Giere suggests that an appreciation of this fact helps distinguish naturalism from “methodological foundationism” or the notion that justified beliefs must recur ultimately to a firm basis in immediate experience (394). His account of the geological paradigm shift therefore “assumes agreement that the technology for measuring magnetic profiles is reliable. The Duhem-Quine problem [i.e. the problem that it is logically possible to salvage empirically disconfirmed theories by ad hoc augmentation] is set aside by the fact that one can build, or often purchase commercially, the relevant measuring technology. The background knowledge (or auxiliary hypotheses) are embodied in proven technology” (394). In other words, the actual practice of science (or technoscience) does not require ultimate justificational grounding, and the agreement on technological reliability ensures, according to Giere and contra Kuhn, that disagreeing parties still operate in the same world.

But while I agree that Giere’s description of the way technology is implemented by scientists is a plausible account of actual practice and its underlying assumptions, I question his extrapolation from the practical to the theoretical plane. With regard to technology, I contend, the circle problem resurfaces with a vengeance. As posed by the skeptic, Giere is right, in my opinion, to reject the circle argument as invalidating naturalism’s methodologically self-reflexive application of scientific theories to the theory of science. Our evolutionary history, I agree, genuinely militates against the skeptic’s requirement that we be able to provide grounds for all our beliefs; our survival depends upon an embodied knowledge that is presupposed by, and therefore not wholly explicatable to, our conscious selves. But as extensions of embodiment, the workings of our technologies are equally opaque to subjective experience, even – or especially – when they seem perfectly transparent channels of contact with the world. Indeed, Giere seems to recognize this when he says that “background knowledge (or auxiliary hypotheses) are embodied by proven technology” (394, emphasis added). In other words, scientists invest technology with a range of assumptions concerning “reliability” or, more generally, about the relations of a technological infrastructure to the natural world; their agreement on these assumptions is the enabling condition for technology to yield clear-cut decision-making consequences. Appearing neutral to all parties involved, the technology is in fact loaded, subordinated to human aims as a tool. Some such subordinating process seems, from a naturalistic perspective, unavoidable for embodied humans. However, agreement on technological utility – on both whether and how a technology is useful – is not guaranteed in every case. Moreover, it is not just a set of cognitive, theoretical assumptions (“auxiliary hypotheses”) with which scientists entrust technologies, but also aspects of their pre-theoretically embodied, sensorimotor competencies. Especially at this level, mediating technologies are open to what Don Ihde calls an experiential “multistability” – capable, that is, of instantiating to differently situated subjectivities radically divergent ways of relating to the world. But it is precisely the consensual stability of technologies that is the key to Giere’s contextualist rebuttal of “foundationism.”

Downplaying multistability is the condition for a general avoidance of the circle argument, for a pragmatic avoidance of idealism and/or skepticism. This, I believe, is most certainly the way things work in actual practice; (psycho)social-institutional pressures work to ensure consensus on technological utility. But does naturalism, self-reflexively endorsing science as the basis of its own theorization, then necessarily reproduce these pressures? Feminists in particular may protest on these grounds that the “nature” in naturalism in fact encodes the white male perspective historically privileged by science because embodied by the majority of practicing scientists. What I am suggesting is that the tacit, largely unquestioned processes by which technological multistability is tamed in practice form a locus for the inscription of social norms directly into the physical world; for in making technologies the material bearers of consensual values (whether political, epistemic, psychological, or even the animalistically basic preferability of pleasure over pain) scientific practice encourages certain modes of embodied relations to the world – not just psychic but material relations themselves embodied in technologies. It goes without saying that this can only occur at the expense of other modes of being-embodied.

More generally stated, the real problem with naturalism’s self-reflexivity is not that it fails to take skeptical challenges seriously or that it provides a false picture of actual scientific practice, but that in extrapolating from practice it locks certain assumptions about technological reliability into theory, embracing them as its own. While it is contextually – indeed physically – necessary that assumptions be made, and that they be embodied or exteriorized in technologies, the particular assumptions are contingent and non-neutral. This may be seen as a political problem, which it is, but it also more than that. It is, moreover, an ontological problem of the instability of nature itself – not just of nature as a construct but of the material co-constitution of real, flesh-and-blood organisms and their environments. Once we enter the naturalist circle – and I believe we have good reason to do so – we accept that evolution dislodges the primacy of place traditionally accorded human beings. At the same time, we accept that the technologies with which science has demonstrated the non-essentiality of human/animal boundaries are reliable, that they show us what reality is really, objectively like. This step depends, however, on a bracketing of technological multistability. If we question this bracketing, as I do, we seem to lose our footing in material objectivity. Nevertheless convinced that it would be wrong to concede defeat to the skeptic, we point out that adaptive knowledge’s circularity or contextualist holism is a necessary requirement of human survival, that it follows directly from embodiment and the fact that the underlying biological mechanisms “largely bypass our conscious experience and linguistic or conceptual abilities” (Giere 385). But if we admit that technological multistability really obtains as a fact of our phenomenal relations to the world, this holism seems to lead us back precisely to Kuhn’s idealist suggestion that researchers (or humans generally) may occupy incommensurably “different worlds.” If we don’t want to abandon materialism, then we have to find an interpretation of this idea that is compatible with physicalism.

Indeed, it is the great merit of naturalism that it provides us with the means for doing so; however, it is the great failure of the theory that it neglects these resources. The failure, which consists in reproducing science’s subordination of technology to thought – in fact compounding the reduction, as contextually practiced, by subordinating it to an overarching (i.e. supra-contextual) theory of science – is truly necessary for naturalism, for to rectify its oversight of multistability is to admit the breakdown of a continuous nature itself. To consistently acknowledge the indeterminacy of human-technology-world relations and simultaneously maintain materialism requires, to begin with, that we extend Giere’s insight about biological mechanisms to specifically technological mechanisms of embodied relation to the world: they too “bypass our conscious experience and linguistic or conceptual abilities.” If we take the implications seriously, this means that technologies resist full conceptualization and are therefore potentially non-compliant with human (or scientific) aims; reliance on technology is not categorically different in kind from reliance on our bodies: both ground our practice and knowledge in the material world, but neither is fully recuperable to thought. Extending naturalism in this way means recognizing that not only human/animal but also human/technology distinctions are porous and non-absolute. But whereas naturalism tacitly assumes that the investment of technology with cognitive aims is only “natural” and therefore beyond question, the multistability of non-cognitive investments of corporeal capacities implies that there is more to the idea of “different worlds” than naturalism is willing or able to admit: on a materialistic reading, it is nature itself, and not just human thought or science, that is historically and contextually multiple, non-coherently splintered, and subject to revolutionary change. Serious consideration of technology leads us, that is, to embrace a denatured naturalism, a techno-evolutionary epistemology, and a material rather than social constructivism. This, then, is the basis for a postnatural philosophy of media.