Following my talk on affective seriality in contemporary television, I am pleased now to present the text of my colleague Felix Brinker’s talk, also delivered last weekend at the “It’s Not Television” conference in Frankfurt. Like much of Felix’s work, this piece on conspiracy as a mode of narrative complexity brings perspectives from critical theory and new materialism to bear on recent discussions in cultural media studies and television studies, thus opening a space for an important dialogical and critical intervention.

Narratively Complex Television Series and the Logics of Conspiracy – On the Politics of Long-Form Serial Storytelling and the Interpretive Labors of Active Audiences

Felix Brinker

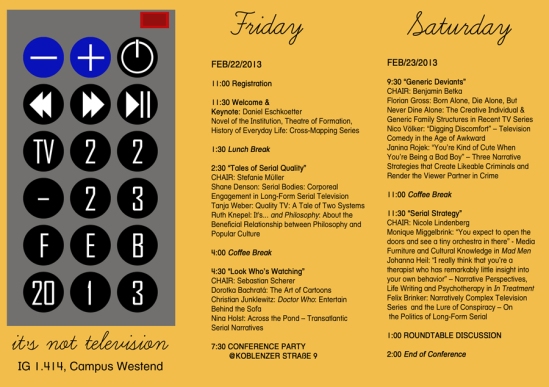

Operating within a television landscape that is characterized by the increasing competition between different media formats, American prime-time dramas of the last 15 years have relied strongly on complex strategies of serialized story-telling in order to ensure viewers’ sustained and ongoing investment in their narratives. Assessing this shift away from earlier norms of episodic closure, media scholar Jason Mittell has labeled the last two decades of American television an era of “narrative complexity” (cf. 29). Narratively complex shows, he argues, capitalize on the possibilities of the serial format and emphasize continuous, serial narration over episodically contained plots; over time, these shows therefore tend to amass complicated webs of backstories and character relationships and thus ask their audiences to engage in, as he puts it, “an active and attentive process of comprehension” (Mittell, 32). Today, I would like to focus on a particular subset of narratively complex shows, namely those that present their over-arching story-lines as an investigation into a central mystery, and that develop this motif as a framing narrative over the course of several seasons, if not the entirety of their runs. Shows like Lost, 24, Rubicon, Homeland, or Fringe all similarly rely on series-spanning story-lines about far-flung intrigues and enticing mysteries. By doing so, these shows adapt the formula that turned earlier series like The X-Files or Twin Peaks into fan-favorites: As Jeffrey Sconce puts it, the ongoing story-lines of these shows “cultivate a central narrative enigma” (107) – like the alien invasion slash government cover-up on The X-Files or the murder of Laura Palmer on Twin Peaks, the mysterious events of Lost’s island, or the uncertain loyalties and motivations Homeland’s prisoner-of-war-cum-terrorist Brody – and use it as a central narrative hook to transform casual viewers into committed loyals. Due to their focus on long-running storylines, these shows exhibit a tendency to become more and more complex over time; despite (or maybe because of) this increasing complexity, many of the shows that follow this model of storytelling have become critical and commercial successes.

Unsurprisingly, then, a considerable number of recent programs have sought to replicate the storytelling strategies of hit shows like Lost – and mystery-centric series can by now be considered a mainstay of American television. In this paper, I would like to take a closer look at the narrative strategies shared by these programs and outline the specific audience practices such shows invite. I argue that the narrative logics of these series are best understood if we conceptualize them as conspiracy narratives – that is, as series that tell stories that center on their protagonists attempts to expose and put a stop to the nefarious workings of mysterious, hidden powers. By adhering to the logics of the conspiracy narrative, these shows aim to provoke a particular way of watching television, an active and attentive audience behavior that entails the readiness to engage in speculations about the unfolding narrative, and to pay close, almost obsessive attention to details. These shows can thus be understood as sharing a specific “narrational mode,” as David Bordwell puts it, with “a historically distinct, [shared] set of norms of narrational construction and comprehension” and can be considered a distinct subset of narratively complex programs (Bordwell 150, cf. Mittell, “Narrative Complexity” 29).

Shows that adhere to such a ‘conspiratorial mode of storytelling’, as I call it, are crime fictions of a grand (or, at times, even cosmic) scope: in them, the story-world has been thrown into chaos and turmoil by the actions of a vast conspiracy, and the story unfolds as the protagonists seek to reconstitute order and attempt to thwart the evil plans of the conspirators. The overarching story-arcs of these shows proceed from the investigation of an initial, isolated event – a puzzling murder or an unexplained plane crash, for example – and promise to eventually offer resolutions for this mystery. Over the course of the series, however, this promise is invariably left unfulfilled, as the protagonists’ further adventures soon reveal that the initial event is only one in a larger chain of mysterious occurrences that are all orchestrated by powerful hidden forces. As the protagonists of these series with each episode venture further into the heart of the mystery, final resolutions or explanations never materialize, as the greater scheme or master-plan turns out to be too vast and to intricate to be fully explored. The ongoing storylines of these shows thus adhere to what scholars of conspiracy like Michael Barkun or Mark Fenster have described as the organizational logic of the conspiracy narrative: as these series progress, their protagonists gain insight into the hidden plans of their scheming opponents, but, by doing so, the number of unexplained mysteries and unanswered plot questions perpetually multiplies as more and more sinister plots come to light (cf. Barkun 101ff.). Shows like these thus exhibit the same narrative dynamic that Fenster has described for the ongoing storyline of Chris Carter’s The X-Files: the series-spanning story-arcs of such programs move “ineluctably toward[s] closure while continually forestalling it” (150).

These shows’ tendency to continuously evoke a central mystery while perpetually refusing to unveil the truth behind it is therefore the result of their reliance on a potentially open-ended, infinitely expandable narrative structure that lends itself ideally to the needs of serial formats like that of the contemporary prime-time television drama. In general, the protagonists of conspiracy narratives in any medium invariably encounter not an isolated mysterious event, but a whole series of puzzling phenomena that are all somehow connected. Conspiracy fictions therefore always cover more than the events of a singular plot; instead they present themselves as collections of several smaller narratives that are loosely connected and that can hardly be contained within standalone formats like the novel or the movie (cf. Cole 37, Fenster 140). Conspiracy-themed films like Alan Pakula’s The Parallax View or Oliver Stone’s JFK therefore usually offer only limited closure and conclude with ‘open’ endings that leave the guilty unpunished. The format of the narratively complex television series, however, allows the narrative logic of conspiracy to unleash its serial potential, as it privileges open-ended narrative trajectories – simply because television shows become profitable the longer their remain on air. Shows that make use of such a conspiratorial narrative construction, however, also inherit another, more problematic aspect of conspiracy fictions, namely their tendency to “careen towards incoherence” (Fenster 122). As the conspiratorial storyline unfolds over several seasons, the number of mysteries multiplies and the web of interconnected subplots becomes more and more complex – up to a point were it becomes difficult if not impossible to consistently resolve all the open questions. Once the end of a series approaches, conspiratorial television shows thus face the challenge to offer a convincing conclusion and to “resolve the excesses of [its] narrative elements,” (as Fenster has put it with reference to conspiracy narratives in general). Especially for long-running series, this poses a considerable problem – and this circumstance might explain the mixed reactions of viewers to the final episodes of conspiratorial shows like Lost and Battlestar Galactica, for example, which were criticized for precisely such a lack of closure (cf. Anders, cf. Newitz). This phenomenon, however, is less a result of ‘poor’ plotting on the parts of television writers and also not due to a lack of advanced planning or foresight – it rather points us to the basic principles of serial storytelling in general, which, as an unashamedly commercial format, has always been more interested in securing long-term revenue streams than in a classical norms of textual unity, plausibility and coherence (and this, of course, goes back to serial figures like Sherlock Holmes, who had to return from the dead after Conan Doyle had run out of money).

As long as conspiratorial television series are in full swing, however, their refusal to offer definitive and final explanations usually turns out to be to their advantage, as such an openness fosters audience speculation. Since these texts never really reveal what’s behind the conspirators’ schemes, they encourage their audiences to connect the dots, and to come up with explanations for the mysteries that the serial narrative leaves unexplained. These tendencies make the structure of conspiracy narrative ideally suited for the goals of contemporary television authors, as they align well with broader trends within what Henry Jenkins has dubbed convergence culture. Arguing that pop-cultural texts of the convergence era seek to establish long-term relationships with their audiences, Jenkins has noted that contemporary programming aims to capture viewers’ attention beyond the narrow-time frame of the television hour. Contemporary television authors, he argues, seek to attract viewers that “give themselves fully over to [their favorite programs]; [who] tape them and may watch them more than one time; [and who] spend [a considerable amount] of their social time talking about them“ (Convergence Culture 74). By inviting their audiences to get to the bottom of their narrative enigmas, conspiratorial television shows encourage precisely such a behavior – and user activity in online forums dedicated to the discussion of shows like Lost, 24, Fringe, or Homeland attests to the validity of this claim.

These developments are far from being new; even in the early 1990s, fans of Twin Peaks and The X-Files took their speculations about these programs to Usenet discussion boards and mailing lists (cf. Jenkins “Do You Enjoy;” as well as Clerc). With the increasing availability of digital video formats, time-shifting devices, and widespread Internet access, however, such audience practices have arguably become more mainstream, and by now play an important part in the considerations of television producers and authors. More recent shows therefore take great care to keep fan speculations going; Lost and Fringe, for example, notoriously disperse plot-relevant clues and hints about their mysteries throughout their narratives (as well as across associated official paratexts like video games, alternate-reality games, or websites that accompany the series). A prominent example of this practice is Lost’s infamous “Blast Door Map” that appeared in “Lockdown,” the 17th episode of the show’s second season. This episode features a brief scene in which John Locke gets pinned down by a closing blast door after things go wrong in the mysterious ‘hatch.’ While waiting for help, the hatch’s lights suddenly go out and black light lamps flicker on instead – the scene then briefly offers the viewers a glimpse of a mysterious map painted on the door with fluorescent colors. In the episode itself this map is visible for barely 6 seconds, but on Lostpedia, fans soon engaged in detailed analyses of what they saw as an intriguing clue to the show’s mysteries. Based on enlarged screen captures from the episode, users soon deciphered the barely legible notes written on the map and parsed out references to earlier events. As it turned out, viewers who paid no attention to this scene did not miss anything important, as the map did not achieve greater relevance for the show’s ongoing narrative – nonetheless, the blast door map presented itself as a riddle to be solved, and the activity of Lostpedia users was not deterred by the fact that this event did not have a deeper meaning after all.

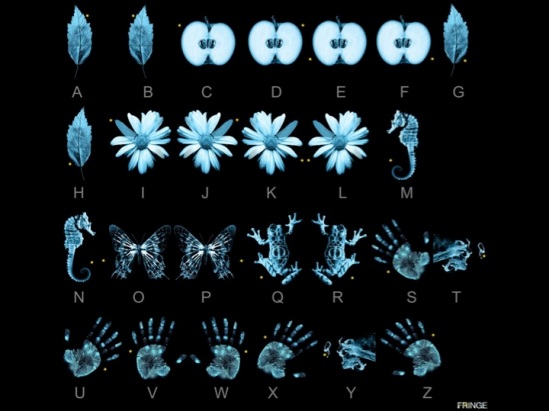

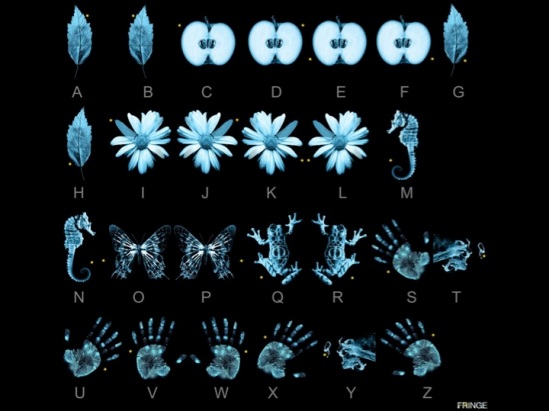

Other shows follow similar strategies to encourage fan speculations: each episode of Fringe, for example, features barely noticeable clues about the events of future episodes in the background of the mise-en-scène. Virtually every episode of this series features subtle links to future adventures of the protagonists, usually directly referring to events that will play out in the coming week: the logo of a plot-relevant bio-tech company emblazoned on a coffee cup and visible for little more than the blink of an eye, for example, or graffiti in the background of street scenes that allude to the plot of the following episode. Fringe, however, does not limit its dissemination of clues to its diegesis: every episode features several symbol-bearing title cards that appear before commercial breaks. These symbols, as enterprising viewers have since discovered, correspond to letters of the alphabet and, once deciphered, spell out a word that resonates with the theme of each week’s episode. Obviously, not all of the shows that subscribe to the logics of the conspiracy narrative rely on similarly baroque strategies to encourage audience speculation (although Christian Junklewitz has shown yesterday that his happens on Doctor Who as well) – in fact, more down-to-earth series like Homeland or Rubicon rather rely on more conventional means to further their mysteries and include relevant bits and pieces of information in snippets of dialogue or have their characters act out suspicious behavior. What these shows nonetheless share is the awareness that the evocation of a narrative enigma is a key element in the attempt to ‘activate’ audiences and foster their commitment to the series.

Perhaps the most baffling aspect of such committed audience practices is the amount of work and time that dedicated viewers invest to unearth and analyze the hidden clues presented by conspiratorial television series. As my examples from Fringe and Lost suggest, spotting the clues and hints hidden within these television texts requires a meticulous, almost obsessive attention to detail and the readiness to engage in time-consuming and laborious close readings of scenes and even individual frames. In his book on Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins has famously argued that such online fan practices should be considered as examples of a ‘collective intelligence’ at work, i.e. as fundamentally democratic, communal problem-solving processes that might “be preparing the way for a more meaningful public culture” (Convergence Culture 228, cf. also 206-239). Participating in such collective processes of interpretation and communication – themselves made possible through the participatory character of social media – could ultimately, Jenkins argues, “create new kinds of political power” and also foster democratic decision-making processes offline. While Jenkins might have a point when it comes to the collaborative practices in online forums, I think such a view of the political significance of these phenomena is all too optimistic and essentially unfounded. As Steven Shaviro notes in his Post-Cinematic Affect, “aesthetics does not translate easily or obviously into politics“ (138) – and neither do specific ways of engaging with a text somehow directly translate into political engagement. While the thematic preoccupations of conspiratorial television series with issues of power and corruption might invite politicizing readings, the claim that political engagement emerges directly from online fan practices can hardly be backed by empirical evidence. The existence of time-consuming and work-intensive audience activities, I argue, rather points us to the character and social function of recreational leisure activities under the regime of contemporary capitalism in general. In an essay titled “Free Time”, Theodor W. Adorno argued that recreational activities, like the consumption of mass or pop-cultural texts, serve the important function of re-constituting the individual’s capacity to work and to take part in social life in general. “Free time,” he points out, is “shackled to its opposite”; recreational activities should therefore not be conceptualized as radically opposed to and separate from work but as an area of social life whose function is always defined in relation to the sphere of labor (187, cf. 187-190). Leisure activities like watching a movie or reading a novel promise a temporary escape from the toils and troubles of the daily routine, he argues, but at the same time, the character of these practices are determined and delimited by their potential to contribute to the reproduction of the individual’s labor-power (or “Arbeitskraft”). Viewed from this perspective, the time-consuming and cognitively challenging audience practices inspired by narratively complex television series take on a political significance that is quite different from the one attested by Jenkins. In this context, American Studies scholar Frank Kelleter has recently pointed to the overlap between the cognitive demands of contemporary popular culture and the professional skills required in the working environments of our present: By inviting active and sustained interpretive practices, Kelleter argues, contemporary television series

call up precisely those skills which characterize the neoliberal labor routines in the age of digitalization: network-thinking, situational feedback, dispersed processing of information, multitasking and, last but not least, the readiness to no longer differentiate between work and leisure. (Kelleter,“Serien als Stresstest” – my translation)

The interpretive practices of committed television viewers thus point us to the fact that engaging with contemporary popular culture has become more and more like work – a particular kind of work, to be exact, namely one that consists chiefly of the production, handling, and interpretation of information (and Jason Mittell’s claim that active viewers might now approach shows as ‘amateur narratologists’ also seems to point us to this). Maurizio Lazzarato has labeled this kind of work “immaterial labor” and argued that it has replaced manual and industrial labor as the predominant form of work in post-industrial societies. Increasingly geared toward producing the “informational and cultural content” of commodities rather than the material production of things, immaterial labor blurs the boundaries between labor and leisure and coincides with the emergence of increasingly automated, computerized, and networked working environments (Lazzarato 1996, 132, cf. 136-137). Active viewers who engage in the detailed analysis and online discussion of their favorite shows perform precisely such a labor, which productively contributes to the popularity and the accessibility of television texts – but they do so unpaid, without any financial compensation for their work.

Instead of too rashly celebrating such practices as fundamentally democratic or even politically subversive, as cultural studies scholars at times tend to do, I argue, we should consider their emergence as indicators of an increasing permeability of the borders between labor and leisure under the regime of contemporary capitalism.

Works Cited:

Adorno, Theodor W. “Free Time.” The Culture Industry. Selected Essays On Mass Culture. J.M. Bernstein, ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2001. 187-197.

Anders, Charlie Jane. “Lost Was the Ultimate Long Con.” io9.com. 23 May 2010. Web. 28 Oct. 2012. <http://io9.com/5545911/lost-was-the-ultimate-long-con>.

Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy. Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley: Unviersity of California Press, 2003.

“Blast Door Map.” Lostpedia. The Lost Encyclopedia. Wikia. Web. 22 Feb. 2013. <http://lostpedia. wikia.com/wiki/Blast_door_map>.

Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Clerc, Susan J. “DDEB, GATB and Ratboy. The X-Files’s Media Fandom Online and Off.” Reading the X-Files. David Lavery, Angela Hague, and Marla Cartwright, eds. Syracruse: UP, 1996. 36-51.

Cole, Samuel Chase. Paradigms of Paranoia. The Culture of Conspiracy in Contemporary American Fiction. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

Fenster, Mark. Conspiracy Theories. Secrecy and Power in American Culture. Revised and updated edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Hagedorn, Roger. “Technology and Economic Exploitation: The Serial as a Form of Narrative Presentation.” Wide Angle 10:4 (1988): 4-12.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: UP, 2006.

—. “‘Do You Enjoy Making the Rest of Us Feel Stupid?’ alt.tv.twinpeaks, the Trickster Author, and Viewer Mastery.” Fans, Gamers, and Bloggers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: UP, 2006. 115-133.

Junklewitz, Christian. “Doctor Who: Entertain Behind the Sofa.” Paper presented at conference “It’s Not Television.” Institut für England- und Amerikastudien, Goethe University of Frankfurt. 22-23 February 2013.

Kelleter, Frank. “Serien als Stresstest.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 4 Feb. 2012. 31. Print.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. “Immaterial Labour.” Radical Thought in Italy. Eds. Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. 132-146.

Mittell, Jason. “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television.” The Velvet Light Trap 58 (Fall 2006): 29-40.

Newitz, Annalee. “As Battlestar Ends, God Is in the Details.” io9.com. 21 Mar. 2009. Web. 28 Oct. 2012. <http://io9.com/5178522/as-battlestar-ends-god-is-in-the-details>.

“Next Episode Clue.” Fringepedia. The Extensive Encyclopedia of Fringe Knowledge. Web. 22 Feb. 2013. <http://fringepedia.net/wiki/Next_Episode_Clue>.

Sconce, Jeffrey. “What If?: Charting Television’s New Textual Boundaries.” Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition. Eds. Lynn Spigel and Jan Olsson. Durham: Duke UP, 2004.

Shaviro, Steven. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zero Books, 2010.