Below you’ll find the talk that Ruth Mayer and I recently gave at the

“Popular Seriality” conference in Göttingen (June 6-8, 2013). We will be expanding the paper for publication, so comments and criticisms are very welcome!

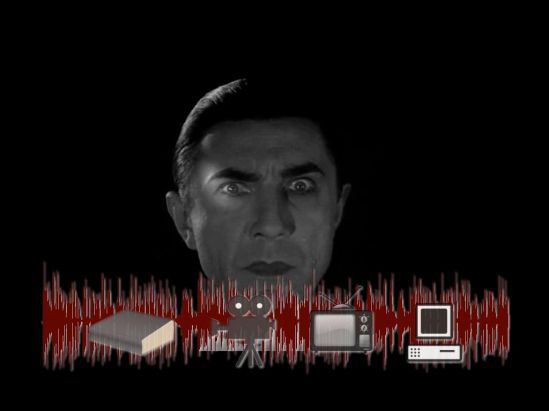

Spectral Seriality: The Sights and Sounds of Count Dracula

Shane Denson, Ruth Mayer – Leibniz Universität Hannover

1. Introduction

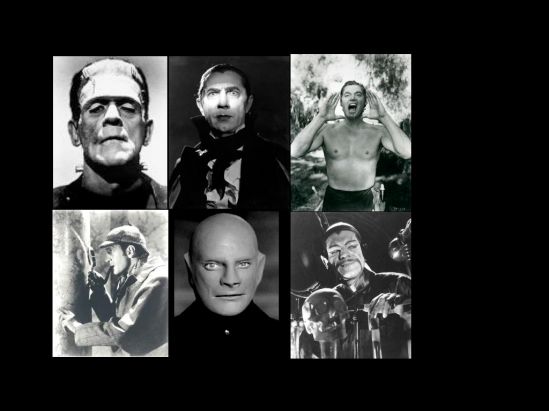

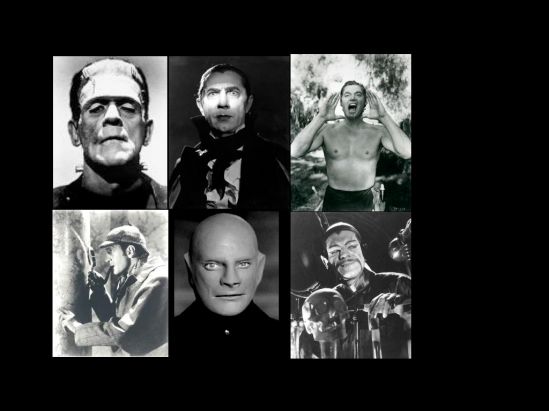

In this talk we will be looking at the medial logics and serial dynamics of iconic popular figures, taking Dracula as a paradigmatic example of a “spectral” logic that enables serial figures to proliferate across medial channels. By “serial figure,” we mean a type of stock character populating the popular-cultural imagination of modernity; a “flat” and recurring figure, subject to one or more media changes over the course of its career. We see serial figures as integral and ideologically powerful components of the political and economic order of modernity, which works expansively to increase commensurability and connectivity. Serial figures operate in this system as mediating instances between the familiar and the unknown, the ordinary and the unusual. It is thus not by accident that such figures are characteristically liminal, transitional, or border-crossing beings – straddling the divide between nature and technology like Frankenstein’s monster, between life and death like Dracula, human and animal like Tarzan, or oscillating between moral and ethnic positions like Sherlock Holmes, Fantômas, or Fu Manchu. These figures parasitically appropriate the media ensembles of a given period, taking up residence in them and making them their own; at the same time, serial figures are in a way themselves media of modernization, higher-order media that gather together and focus attention on media undergoing change. This is especially true with regard to the cultural and commercial logic of the “update,” according to which transformations and transitions in the modern media landscape are negotiated and sold as “innovations.” But characterized as they are by a reversible relation to media as both instrument and environment – as both (diegetic) object of interest and as the very horizon of perception, expression, or narration – serial figures lend themselves also to a retrospective view of media change as non-teleological, overdetermined by competing forces and yet haunted by a spirit of indeterminacy and a sense that “things could have been otherwise.”

In the following, we will first try to flesh out this picture and explain more precisely what a serial figure is, what it does, and how it operates. Our focus will be on the figure of Dracula, who perhaps more than any other serial figure brings into focus what we’re designating the “spectral” logic of serial proliferation: that is, a ghostly and flickering relation to presence, or the present, which characterizes the medial historicity of the serial figure and propels its ongoing transformations as it moves between old and new media – from text, to film, to radio, TV, and toward the digital. Seen in this light, it is the spectrality of the figure, the fact that it’s neither (completely) here nor there, that keeps the figure alive – or, more precisely, undead – never quite exhausted by a single, definitive instantiation but always at least potentially available for yet another serial iteration.

2. Serial Framings & the Spectral Integrity of the Icon

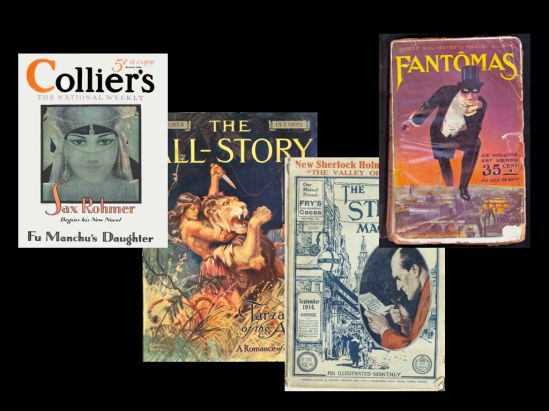

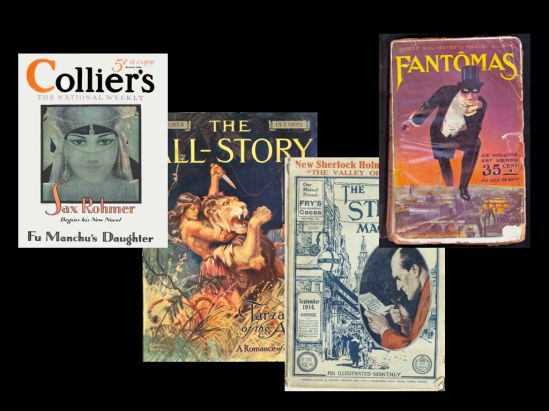

A serial figure is a figure that needs no explanation, no introduction, and no elaborate framing – it is familiar, even if one has never dealt explicitly with the figure. The serial figure is distinguished here from the series character, which is developed in an ongoing narrative (for example, a soap opera, a serial novel, or a saga). Serial figures – as Umberto Eco once wrote of Superman – undergo a “virtual beginning” with each new staging, “ignoring where the preceding event left off.” Series characters grow and develop a more or less linear biography, while serial figures are characterized by repetitions, revisions, and even the occasional “reboot” of their entire history. Serial figures and series characters must, however, be understood as ideal-typical figurations; often, they blend into one another in the course of their narrative unfolding. Indeed, serial figures quite often derive from series characters: many (like Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Fu Manchu, Fantômas) were first introduced in the continuing narratives of serialized magazine productions, then further developed in novel series, before eventually mutating into serial figures proper as they jumped across various medial channels (Denson/Mayer 2012a/b).

Serial figures have an extreme affinity to modern media, and they seem positively to thrive on media changes. Though many classical serial figures were established in literary texts, they all jumped very quickly to other media, mutated, fanned out, proliferated, and reproduced without losing their distinctive forms, features, trademark equipment or gear. As a result, they are particularly good at introducing the cultural or medial “new,” and thus at mediating novelty against the background of a figure’s familiarity – serial figures both foreground or exoticize and familiarize the foreign or unknown. This marking and familiarization is achieved not only narratively, but also formally – by way of serial iteration. Serial figures are not developed linearly from A to B; rather, their careers unfold along branching paths, across nodes, loops, and resonances, by way of a “concrescent” or compounding, sedimenting rather than sequential form of seriality.

Even before the comics superheroes of the 1930s took up and adapted many of their characteristics, serial figures presented themselves as both long-familiar and strangely new, at once timeless and hypermodern, universal and particular alike. For a long time, however, the serial figures of the turn of the century have been read almost exclusively in terms of the atavistic, the primitive, the unconscious – in any case, not the modern. This approach culminated in the 1960s in the reception history of Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism. For Dracula, Frye’s impact registers in the assumption of a “majestic immutability” informing the representation of the vampire through the ages, as Nina Auerbach delineated in her cultural history of the vampire (1995: 130; cf. Douglas 1966). This assumption then gave way, in the wake of intellectual history and Foucault’s “archaeology of knowledge,” to a more historically and medially specific approach, as exemplified by Nina Auerbach’s own take on vampires as “personifications of their age” (3): instead of transhistorical continuities, scholarship now foregrounded historical breaks and radical revisions.

But cultural contextualization alone is not enough to get a handle on the cultural careers of serial figures. We have to pay attention both to their iconicity and variability, and towards this end we have to focus on the serial figure’s mediality – or, more generally: its formal framing. To understand the constructive force of such framing, one should not stretch the frame too far. If you look not at Tarzan, but at primate-human hybrids in the history of Western culture, not at Dracula but the vampire from Byron to True Blood, not Frankenstein’s monster but man-machine configurations since the early modern era – you run the risk of overlooking the specific medial dynamics of popular seriality, a dynamics of modern and hence mass and technical media. Connected to the inherent reproducibility of modern media, this properly serial dynamic draws on an awareness of something being re-told, activating a dialectics of recognition and astonishment, of departures from and re-anchorings of previously staged narratives and images. The more concrete the anchor points and cross-references in a serial sequence, the more clearly does this logic manifest itself. And only with regard to this logic can we recognize the political-ideological and medial-material “work” of the serial figure, its anchoring in a specific world-historical era.

Dracula himself is very much a product of the late colonial era, and the threat he poses is accordingly “dynamic, totalizing.” Earlier monsters operated “on the margins of society, hidden away in their towers,” while modern creatures of horror are figures of expansion and spread. “The modern monsters,” writes Franco Moretti with a view particularly toward Dracula, “threaten to live for ever and to conquer the world. For this reason they must be killed” (Moretti 1982: 68). Dracula, not the generic vampire, comes from Transylvania, and thus from the border region between East and West; a region which does not yet demarcate horror and superstition at the time of the figure’s inception but “the vexed ‘Eastern Question’ that so obsessed British foreign policy in the 1880s and 90s” (Arata 1990: 627; see also Richards 1993: 56-64; Gibson 2006). In our minds, Dracula always has pointed teeth, he always wears a cape, always sleeps in a coffin, and he concentrates on female victims, even if he got along during various stretches of his serial career without some of these habits and accoutrements. In its iconicity, the figure of Dracula mobilizes a whole army of basic conceptual oppositions, pitting them against one other, but without the prospect of resolution: East meets West, the predator threatens civilized humanity, masculine agency preys on the female victim – and, of course, life and death entwine in the vampire’s uncanny body. None of these pairs of terms remains unproblematic or stable in the course of the figure’s long career, but all of them reappear again and again in various guises and constellations. In his serial specificity, Dracula thus stands out among vampires – he no longer embodies the sensibility of the early Victorian period, nor yet has he assumed that of our late televisual postmodernity. There is a diffuse – indeed spectral – integrity to the figure across its various medial instantiations; its iconic appearance will always by superimposed upon any and all possible concrete manifestations, even if (and perhaps especially if) the figure now appears in a different form.

3. Dracula’s Medial Dialectics

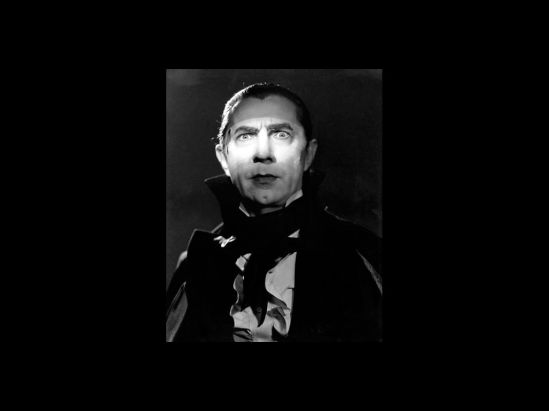

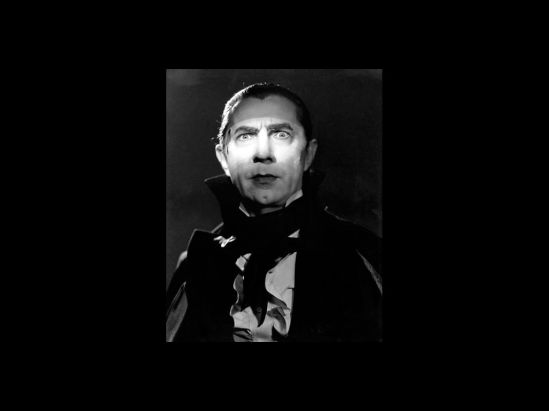

The figure’s iconic form has been fixed for us above all by Bela Lugosi’s portrayal of the Count in Tod Browning’s 1931 film version, to which we will return shortly, but first we turn briefly to Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel from which the figure first sprang to … uhh … “life.” The source text helps us to see the presence of a further conceptual pair at work in the serial unfolding of the figure: for the novel is marked, in a way that problematically straddles its diegetic “inside” and its medial “exterior,” by an unsettled tension between the diversification of media and an effort to commensurabilize or contain them. This tension is energized by the spirit of a transitional phase in which the medium of the novel – still the master medium of entertainment in the late Victorian era – starts to cede its territory to the technical mass media that shaped entertainment in the twentieth century. As we shall see, the unresolved tension between the specificity and generality of mediation is also generative of the sights and sounds of Count Dracula as he proliferates serially across the century’s audiovisual channels.

More than perhaps any other serial figure, Dracula reveals the active and creative power of technical media already at his literary point of departure. In Thomas Elsaesser’s estimation, which follows Friedrich Kittler’s seminal reading in Aufschreibesysteme, “[Dracula] may be the only original and authentic myth that the age of mechanical reproduction has produced” (2011: 111). Kittler read Dracula as “that perennially misjudged heroic epic of the final victory of technological media over the blood-sucking despots of old Europe” (Kittler, 1999: 86). And Kittler was not the only critic to read the novel as the document of a media struggle, in which an alliance built on modern media of communication is pitted against an ancient and totalitarian power (see also Wicke 1992; Richards 1993). While we very much agree that Dracula should be read as a novel about mediatization and media change, however, we are not so sure about its actual position within this battle – its sympathies, as it were. Technical media may prove superior in the battle of forces that the novel both depicts and takes part in. But the alliances or opposing camps within this battle are far less clear-cut than one might think. This may have to do with the fact that the triumph of the technical media of entertainment was about to deal a fatal blow to the very medium of the novel. The very particular novel at hand, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, does not openly militate against the media system of the twentieth century, we argue. But it is by no means as celebratory of its own format’s impending replacement as is often assumed.

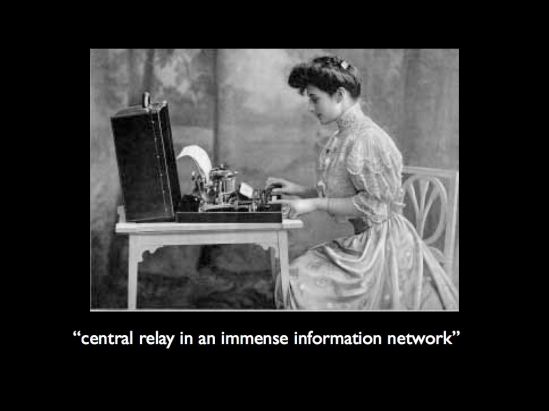

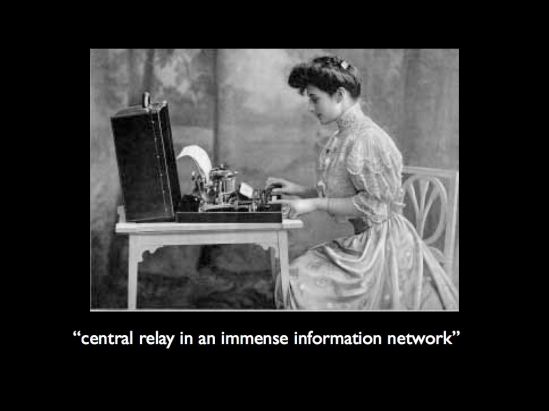

In line with this reconsideration of alliances and tensions, we contend that Dracula serves not so much as an outdated antecedent to the mass-media cultures of modernity, but as an integral element – perhaps even a basic principle – of them. Already at the point of his literary inception, Dracula embodies a principle of diffusion, of intermedial spectrality, according to which one material form is translatable into another: the humanoid, the wolf, bat, and fog. This allows him for a time to elude his pursuers, but they too are acquainted with a plurality of media forms: shorthand notation, the telegraph, the phonograph, and the typewriter play instrumental roles in this counter-project. Mina Harker, as Dracula’s most important opponent and the driving engine of the international alliance of vampire hunters in the metropolis, is a skilled typist, and she manages to render the fractured records of journals, newspapers, phonograph cylinders, and stenographic notes into the uniform medium of typewritten text, reproduced in triplicate; Mina becomes what Kittler called the “central relay in an immense information network” (Discourse Networks 354). In doing so, however, Mina also cleanses the new technological media of communication of their ‘rawness’ and authenticity: “I have copied out the words on my typewriter, and none other need to now hear your heart beat, as I did” (199), she reassures Dr. Seward after having reviewed his phonograph cylinders. Simultaneously, and interestingly, she defuses what could be considered the most powerful forcefield of the late Victorian novel, obliterating the traces of feeling, the trembling and the terror, the horrible events’ profound impact on the ‘soul.’ At the very end of the novel, her husband, Jonathan Harker, summarizes in frustration that “in all the mass of material of which the record is composed, there is hardly one authentic document; nothing but a mass of type-writing […]. We could hardly ask anyone, even did we wish to, to accept these as proofs of so wild a story” (335).

Fortunately, the version of the events that the book ultimately renders is not Mina’s purified, streamlined, typewritten collection of data, but Bram Stoker’s lurid and sprawling ‘imperial gothic’ (Brantlinger 1995). With this, the novel counters the “modern” ideal of totalizing data processing with another, older, aesthetics of totality – collating voices, perspectives, and media in order to achieve an impression of synchronicity and homogeneity. Dracula thus displays its tacit predilection for the media system of the nineteenth century and its unacknowledged skepticism vis-à-vis the technical media of the upcoming age. But the novel is fighting a losing battle on behalf of its own format. At the novel’s end, Dracula will be defeated while Mina has just given birth to a son, who shall bear all the first names of the league of vampire hunters. But, alas, in the story’s longer run, the powers of reproduction are afforded to the vampire rather than the Victorian lady. What distinguishes Mina in the novel – her interiority, her reflection, her robust presence – disqualifies her for a serial career and confines her to the bounds of the book. Dracula, in contrast, who is hardly ever ‘there’ in the novel, transgresses its boundaries and lives on, by virtue of his capacity to defer closure and synchronicity.

Rooted diegetically in the serial infection process by which the curse of the undead spreads, Dracula’s power far exceeds the text’s limits, formally and materially resisting the closure of the work. Dracula taunts his pursuers: “My revenge is just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side. Your girls that you all love are mine already; and through them you and others shall yet be mine […]” (273). In his flickering dispersion he seems to project various options for a future vampiric existence, tentatively envisioning nodes and links to future versions of himself. In that respect, the novel functions – against its own best interest and almost as if being operated by an alien force – as the ideal starting point for the figure’s serial proliferation.

Dracula’s spectral quality resides in his uncanny ability to navigate not only (diegetic) time and space but also to spread diffusely through the very real experiential timespaces that rub against one another in modernity, in the oppositional trajectories of medial particularization and convergent totalization. Transcending the novel – which is itself a site of convergent mediality wherein distinctions are effaced in the effort to correlate, coordinate, and ultimately thus to entomb the shape-shifting villain – Dracula emerges as a higher-order medium, thus acting simultaneously as a parasitic harbinger and a host of media transformation. The meta-medium of the serial figure accentuates the insufficient totality or completeness of the book as compared to audiovisual media – the media of silent and sound film, radio, and television into which the Count will successively and temporarily descend, before he inevitably pulls up stakes (so to speak) and moves on. In this interplay of first-order and second-order media, or between medial specificity and comparability, the sights and sounds of Dracula become the sights and sounds of media change itself.

4. The Icon as Transitional Medium

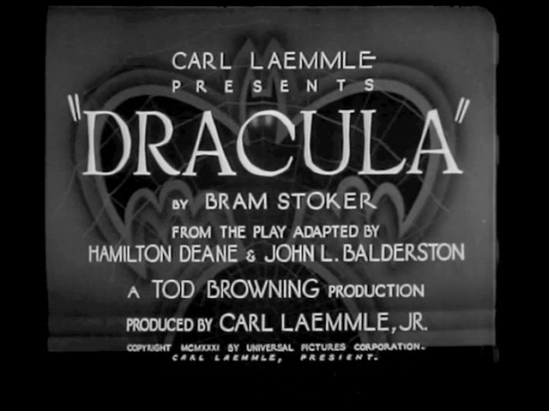

The transitional interplay of medial figure and ground is nowhere so tightly focused as in Tod Browning’s classic film from 1931 – particularly in the iconic image it bequeaths to us of Count Dracula. The film’s title card already evidences the plurimedial seriality that the figure had amassed over the previous three decades: “Carl Laemmle presents Dracula by Bram Stoker” – not as a direct adaptation of the novel, but “from the play adapted by Hamilton Deane & John L. Balderston,” which in fact refers to two plays: first a London-based production from 1924 and then a 1927 Broadway play based on it, and starring Bela Lugosi. Not mentioned here are Stoker’s own theatrical production, performed only once (prior to the novel’s publication) for the purpose of securing a copyright, Friedrich Murnau’s unauthorized adaptation Nosferatu from 1922, or any of the print editions, adaptations, abridgments, and serializations that had appeared since 1897. But what’s about to appear on screen will in any case overshadow all of those past interpretations, including the original novel, and it will continue to color our perception of any future instantiation for decades to come. Significantly, Browning’s film kicks off the horror-film cycle of the 1930s, including a series of Universal Studios productions featuring the Count: after Dracula (1931) comes Dracula’s Daughter (1936), then Son of Dracula (1943), the monster mash-ups House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), and finally Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), in which Lugosi reprises his role one last time. The figure, like the horror film, changes markedly over the course of this series, though, so it’s easy to lose sight of the originary medial functionality of Lugosi’s icon, which is born in the wake of the transition from silent to sound film. By film historian Donald Crafton’s reckoning, this transition was coming to its end by the time Dracula appeared in February 1931, but as Robert Spadoni has argued, the film harnessed a lingering experience of the first sounds moviegoers had heard emitted from the screen – an uncanny or “ghostly” experience resulting from the incomplete phenomenal coordination of sound and image. The Count gave a body to this recently bygone (but unforgotten, “undead”) experience, around which the horror genre itself was initially fashioned.

In this context, Browning’s film re-enacts the novel’s battle between medial particularization and generalization – abstracting it, though, from Mina’s and Stoker’s divergent efforts to coordinate medial fragments into a coherent textual whole, and transferring it to a probing of the cinema’s recent efforts to coordinate sight and sound into a coherent audiovisual whole. Dracula’s body is the central site of the struggle, the medial stakes of which are made clear in the film’s first ten minutes or so, leading up to the Count’s appearance and first encounter with his guest. The non-diegetic music with which the film opens will cease after the opening credits, and it will not reappear again until the closing credits. But the opening scene, set inside a noisy horse-drawn coach traveling through Transylvania, locates us more or less unproblematically in the sound-era of cinema, as onscreen characters converse and produce audible dialogue. Soon, though, as we move deeper into the wilds of Transylvania, this will stop and give way to an eerie silence. When the sun sets and our traveler Renfield (here playing the role of the novel’s Harker) sets out for Borgo Pass, a series of images show the Count’s distant castle, first from the outside, then its interior, bringing us swiftly to his coffin. There is no sound at all, until the interminable silence is broken by the sound of coffins opening, creaking, bumping, then rats squeaking, wolves barking, howling, as the camera moves in to reveal Dracula, who has silently appeared. The background of silence contrasts palpably with the use of non-diegetic music during the credits. This might be called a non-diegetic silence, as it foregrounds the images as silent, setting the stage for an uncanny sound, very different from the normalized sound of dialogue that precedes it. The silence has, of course, a diegetic aspect, but it is also double in a way, standing out as the spectral presence of a material and medial absence. (By way of contrast, a “regular” (diegetic) silence might conventionally be marked with the sound of crickets chirping.) Renfield’s carriage arriving now at Borgo Pass brings with it – and takes with it again just as quickly – the normalized (i.e. synchronized) sound we saw in the opening sequences, again foregrounding the uncanny silence of Dracula, who awaits Renfield ominously in his own carriage. Renfield’s somewhat fearful words to the silent count – “The coach from Count Dracula?” – seem awkwardly obtrusive against the background of silence, and the aural register itself alternates as ground and figure with the image of the tight-lipped count. Visually, Dracula’s bulging eyes accentuate this interplay, as they themselves describe a partially autonomous figure against the ground of his face – thereby singling out vision and visuality and setting them in a volatile and oscillating relation with sound and the sonic, before the Count’s coach heads off with its passenger toward the castle.

Along the way, Renfield discovers that a bat has silently replaced the driver, and upon arrival he confirms that the driver is missing, while the castle door creaks open – autonomously and ostentatiously. Renfield enters, bats squeak, armadillos rustle. Dracula descends the staircase silently behind the frightened Renfield’s back. “I am Dracula.” Renfield explains hastily he thought he was in the wrong place. Awkwardly, Dracula replies, “I bid you welcome.” Wolves howl in the background. “Listen to them! Children of the night. What music they make.” This self-reflexive foregrounding of sound, captured for the purposes of the uncanny, reimagines the Jazz Singer’s famous “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” It will reverberate again in Tarzan’s yell, and – somewhat paradoxically – also in the muteness of Frankenstein’s monster, all of which stand in a self-reflexive relation to the sound-film transition.

The interplay of silence/sound, noise/speech, visual/sonic continues in London: there we hear the noisy metropolis, the scream of a first offscreen victim, and the music of the opera house, all of which are contrasted with the silence of the house at night, where a bat waits noiselessly at the window, enters without a sound, and where an offscreen transformation allows Dracula to appear just as noiselessly at Lucy’s bedside. This is followed by the screams of the madhouse and its raving lunatics, including Renfield, contrasted with the concentrated silence of Seward and the other doctors, and of van Helsing before he announces that they’re dealing with the undead, Nosferatu. Dracula communicates with Renfield without speech, seemingly with his eyes – which, in the iconic image, are highlighted with precise rays of light, producing an effect much like the bulging eyes earlier, again making vision/the visual the carrier of (a weird, for us indecipherable sort of) information, while sound is alienated from the image and rendered as incomprehensible noise – thus “denaturing” the recently naturalized, modern system of communication via synchronized sound and vision. It is significant that sound is produced, if not as dialogue, only by objects and nonhuman animals, never by the count’s body in humanoid form, which is perfectly and uncannily silent both in motion and at rest. Later, the count’s invisibility in the cigar-case mirror, first noticed by van Helsing, further problematizes sound/image relations, as Dracula is audible while not (mediately) visible. The fact that he “casts no reflection in the mirror” in fact mirrors or translates the fact that his body also emits no sound. Thus, sound and vision are dissociated from one another, both of them operating as channels of significance and its deformation in a joint effort to undo the habitualization of synchronized sound and reveal an experience of disjointedness and material excess at its base. This excess, this spectral materiality, refuses to be contained completely by the new medium of sound film. The latter is shown to be “haunted” by a stubborn spirit of medial transitionality, embodied by Dracula, which resists containment in a neat medial package just as the Count could not be contained in the novel.

The film reinstates, in this way, the excess that Mina, in the novel, had erased in her transcription of Seward’s cylinders. But it does so in a way that sits uneasily with Stoker’s own attempt to restore a novelistic “spirit” to his apparently dying medium. For the film transfers the mechanism of phonography, the technical capture of the aural real, from the level of content to that of the medium, which it self-reflexively foregrounds; accordingly, the material excess of breath (literally, “spirit”) and heartbeat that Mina erased from the cylinders are restored and channeled towards the nervous, embodied reactions of the spectator confronted with the early horror film.

As in the novel, then, but for very different purposes, Dracula again thrives on, marks, and carries forth an unsettling spirit of medial transitionality: whereas Stoker sought to counter the impending changes to the media landscape of the nineteenth century, Browning allows the figure to extend the scope of the cinema’s sound transition – and with it the vampire’s own power. Problematizing the coordination of sound and image, Dracula’s uncanny image continually reinstates the distinction between sonic and visual registers, thus thwarting the medial coherence of the talkie, obstructing the normalization of a generalized audiovisual mediality. Rather than be contained by the medium of the sound film, Dracula himself becomes the medium in which the particular streams of sound and image can appear, juxtaposed and disjoined, forever at battle. Browning’s film thus continues the trajectory of serialization that the Count embarked upon when he escaped and transcended Mina’s and Stoker’s textualizing efforts in 1897. And though the medial self-reflexivity of the icon will fade from view as the sound transition recedes further into the past and the figure further establishes its place in popular culture, it is the icon’s spectral instrumentalization of the unsettled relations between medial particularity and generality that in part ensures its ongoing serial power.