[UPDATE March 7, 2013: Full text of the talk now posted here.]

Following our recent roundtable discussion in La Furia Umana (alternative link here), Therese Grisham, Julia Leyda, Steven Shaviro, and I have submitted a panel proposal on the topic of post-cinematic affect for next year’s conference of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. If the proposal is accepted, I hope to develop in a more systematic way some of the thoughts I put forward in the roundtable discussion, particularly with regard to the role of the “irrational” camera. Here is the proposal I submitted for my contribution to the panel:

Crazy Cameras, Discorrelated Images, and the Post-Perceptual Mediation of Post-Cinematic Affect

Shane Denson

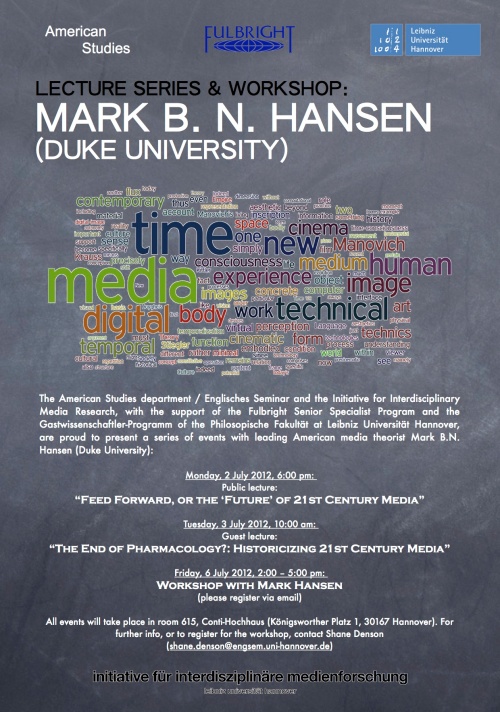

Post-millennial films are full of strangely irrational cameras – physical and virtual imaging apparatuses that seem not to know their place with respect to diegetic and nondiegetic realities, and that therefore fail to situate viewers in a coherently designated spectating-position. While analyses ranging from David Bordwell’s diagnosis of “intensified continuity” to Matthias Stork’s recent condemnation of “chaos cinema” have tended to emphasize matters of editing and formal construction as the site of a break with classical film style, it is equally important to focus on the camera as a site of material, phenomenological relation between viewers and contemporary images. Thus, I aim to update Vivian Sobchack’s film-theoretical application of Don Ihde’s groundbreaking phenomenology of mediating apparatuses to reflect the recent shift to what Steven Shaviro has identified as a regime of “post-cinematic affect.” By setting a phenomenological focus on contemporary cameras in relation both to Shaviro’s work and to Mark B. N. Hansen’s recent work on “21st century media,” I will show that many of the images in today’s films are effectively “discorrelated” from the embodied interests, perspectives, and phenomenological capacities of human agents – pointing to the rise of a fundamentally post-perceptual media regime, in which “contents” serve algorithmic functions in a broader financialization of human activities and relations.

Drawing on films such as District 9, Melancholia, WALL-E, or Transformers, the presentation sets out from a phenomenological analysis of contemporary cameras’ “irrationality.” For example, virtual cameras paradoxically conjure “realism” effects not by disappearing to produce the illusion of perceptual immediacy, but by emulating the physical presence of nondiegetic cameras in the scenes of their simulated “filming.” At the same time, real (non-virtual) cameras are today inspired by ubiquitous, aesthetically disinterested cameras that – in smartphones, surveillance cams, satellite imagery, automated vision systems, etc. – increasingly populate and transform our lifeworlds; accordingly, they fail to stand apart from their objects and to distinguish clearly between diegetic/nondiegetic, fictional/factual, or real/virtual realms. Contemporary cameras, in short, are deeply enmeshed in an expanded, indiscriminately articulated plenum of images that exceed capture in the form of photographic or perceptual “objects.” These cameras, and the films that utilize them, as I shall argue in a second step, mediate a nonhuman ontology of computational image production, processing, and circulation – leading to a thoroughgoing discorrelation of contemporary images from human perceptibility. In conclusion, I will relate my findings to recent theorizations of media’s broader shift toward an expanded (no longer visual or even perceptual) field of material affect.

Bibliography:

Bordwell, David. “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film.” Film Quarterly 55.3 (2002): 16-28.

Hansen, Mark B. N. Feed-Forward: The “Future” of 21st Century Media. Unpublished manuscript, forthcoming 2013/2014.

Ihde, Don. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1990.

Shaviro, Steven. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zer0 Books, 2010.

Sobchack, Vivian. The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1992.

(PS: The crazy mobile camera collection pictured above, the “cameravan,” belongs to one Harrod Blank, whose website is here. The image itself was taken from a website (here) licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.)