In this post, I want to outline some ongoing work in progress that I’ve been pursuing as part of my postdoctoral research project on seriality as an aesthetic form and as a process of collectivization in digital games and gaming communities. The larger context, as readers of this blog will know, is a collaborative project I am conducting with Andreas Jahn-Sudmann of the Freie Universität Berlin, titled “Digital Seriality” — which in turn is part of an even larger research network, the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality–Aesthetics and Practice.” I’ll touch on this bigger picture here and there as necessary, but I want to concentrate more specifically in the following on some thoughts and research techniques that I’ve been developing in the context of Victoria Szabo’s “Historical & Cultural Visualization” course, which I audited this semester at Duke University. In this hands-on course, we looked at a number of techniques and technologies for conducting digital humanities-type research, including web-based and cartographic research and presentation, augmented and virtual reality, and data-intensive research and visualization. We engaged with a great variety of tools and applications, approaching them experimentally in order to evaluate their particular affordances and limitations with respect to humanities work. My own engagements were guided by the following questions: How might the tools and methods of digital humanities be adapted for my research on seriality in digital games, and to what end? What, more specifically, can visualization techniques add to the study of digital seriality?

I’ll try to offer some answers to these questions in what follows, but let me indicate briefly why I decided to pursue them in the first place. To begin with, seriality challenges methods of single-author and oeuvre or work-centric approaches, as serialization processes unfold across oftentimes long temporal frames and involve collaborative production processes — including not only team-based authorship in industrial contexts but also feedback loops between producers and their audiences, which can exert considerable influence on the ongoing serial development. Moreover, such tendencies are exacerbated with the advent of digital platforms, in which these feedback loops multiply and and accelerate (e.g. in Internet forums established or monitored by serial content producers and, perhaps more significantly, in real-time algorithmic monitoring of serialized consumption on platforms like Netflix), while the contents of serial media are themselves subject to unprecedented degrees of proliferation, reproduction, and remix under conditions of digitalization. Accordingly, an incredible amount of data is generated, so that it is natural to wonder whether any of the methods developed in the digital humanities might help us to approach phenomena of serialization in the digital era. In the context of digital games and game series, the objects of study — both the games themselves and the online channels of communication around which gaming communities form — are digital from the start, but there is such an overwhelming amount of data to sort through that it can be hard to see the forest for the trees. As a result, visualization techniques in particular seem like a promising route to gaining some perspective, or (to mix metaphors a bit) for establishing a first foothold in order to begin climbing what appears an insurmountable mountain of data. Of particular interest here are: 1) “distant reading” techniques (as famously elaborated by Franco Moretti), which might be adapted to the objects of digital games, and 2) tools for network analysis, which might be applied in order to visualize and investigate social formations that emerge around games and game series.

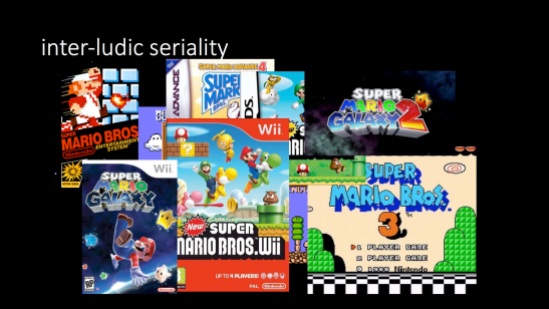

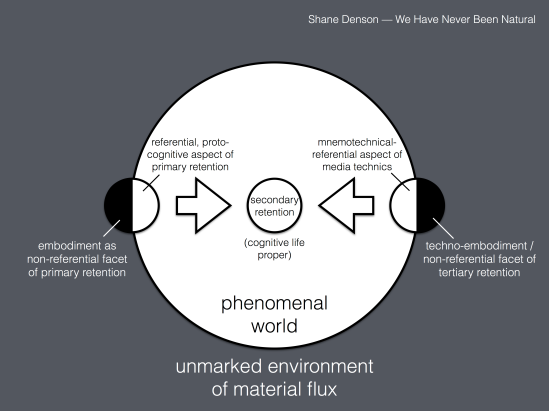

Before elaborating on how I have undertaken to employ these approaches, let me say a bit more about the framework of my project and the theoretical perspective on digital seriality that Andreas Jahn-Sudmann and I have developed at greater length in our jointly authored paper “Digital Seriality.” Our starting point for investigating serial forms and processes in games and gaming communities is what we call “inter-ludic seriality” — that is, the serialization processes that take place between games, establishing series such as Super Mario Bros. 1, 2, 3 etc. or Pokemon Red and Blue, Gold and Silver, Ruby and Sapphire, Black and White etc. For the most part, such inter-ludic series are constituted by fairly standard, commercially motivated practices of serialization, expressed in sequels, spin-offs, and the like; accordingly, they are a familiar part of the popular culture that has developed under capitalist modernity since the time of industrialization. Thus, there is lots of continuity with pre-digital seriality, but there are other forms of seriality involved as well.

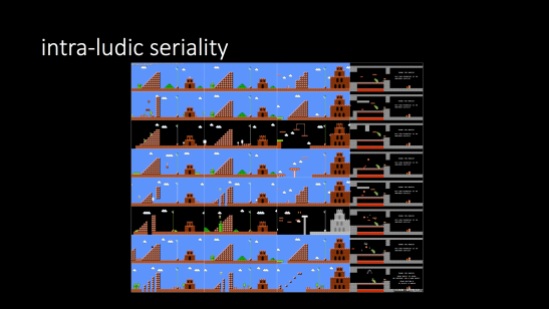

“Intra-ludic seriality” refers to processes of repetition and variation that take place within games themselves, for example in the 8 “worlds” and 32 “levels” of Super Mario Bros. Here, a general framework is basically repeated while varying and in some cases increasingly difficult tasks and obstacles are introduced as Mario searches for the lost princess. Following cues from Umberto Eco and others, this formula of “repetition + variation” is taken here as the formal core of seriality; games can therefore be seen to involve an operational form of seriality that is in many ways more basic than, while often foundational to, the narrative serialization processes that they also display.

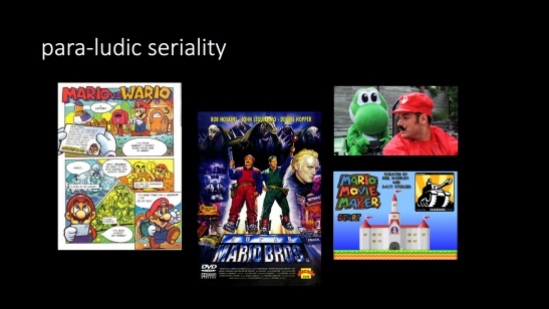

Indeed, this low-level seriality is matched by higher-level processes that encompass but go beyond the realm of narrative — beyond even the games themselves. What we call “para-ludic seriality” involves tie-ins and cross-overs with other media, including the increasingly dominant trend towards transmedia storytelling, aggressive merchandising, and the like. Clearly, this is part of an expanding commercial realm, but it is also the basis for more.

There is a social superstructure, itself highly serialized, that forms around or atop these serialized media, as fans take to the Internet to discuss (and play) their favorite games. In itself, this type of series-based community-building is nothing new. In fact, it may just be a niche form of a much more general phenomenon that is characteristic for modernity at large. Benedict Anderson and Jean-Paul Sartre before him have described modern forms of collectivity in terms of “seriality,” and they have linked these formations to serialized media consumption and those media’s serial forms — newspapers, novels, photography, and radio have effectively “serialized” community and identity throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Interestingly, though, in the digital era, this high-level community-building seriality is sometimes folded into an ultra low-level, “infra-ludic” level of seriality — a level that is generally invisible and that takes place at the level of code. (I have discussed this level before, with reference to the BASIC game Super Star Trek, but I have never explicitly identified it as “infra-ludic seriality” before.) This enfolding of community into code, broadly speaking, is what motivates the enterprise of critical code studies, when it is defined (for example, by Mark Marino) as

an approach that applies critical hermeneutics to the interpretation of computer code, program architecture, and documentation within a socio-historical context. CCS holds that lines of code are not value-neutral and can be analyzed using the theoretical approaches applied to other semiotic systems in addition to particular interpretive methods developed particularly for the discussions of programs. Critical Code Studies follows the work of Critical Legal Studies, in that it practitioners apply critical theory to a functional document (legal document or computer program) to explicate meaning in excess of the document’s functionality, critiquing more than merely aesthetics and efficiency. Meaning grows out of the functioning of the code but is not limited to the literal processes the code enacts. Through CCS, practitioners may critique the larger human and computer systems, from the level of the computer to the level of the society in which these code objects circulate and exert influence.

Basically, then, the questions that I am here pursuing are concerned with the possibilities of crossing CCS with DH — and with observing the consequences for a critical investigation of digital game-based seriality. My goal in this undertaking is to find a means of correlating formations in the high-level superstructure with the infra-ludic serialization at the level of code — not only through close readings of individual texts but by way of large collections of data produced by online collectives.

As a case study, I have been looking at ROMhacking.net, a website devoted to the community of hackers and modders of games for (mostly) older platforms and consoles. “Community” is an important notion in the site’s conception of itself and its relation to its users, as evidenced in the site’s “about” page:

ROMhacking.net is the innovative new community site that aggressively aims to bring several different areas of the community together. First, it serves as a successor to, and merges content from, ROMhacking.com and The Whirlpool. Besides being a simple archive site, ROMhacking.net’s purpose is to bring the ROMhacking Community to the next level. We want to put the word ‘community’ back into the ROMhacking community.

The ROMhacking community in recent years has been scattered and stagnant. It is our goal and hope to bring people back together and breathe some new life into the community. We want to encourage new people to join the hobby and make it easier than ever for them to do so.

Among other things, the site includes a vast collection of Super Mario Bros. mods (at the time of writing, 205 different hacks, some of which include several variations). These are fan-based modifications of Nintendo’s iconic game from 1985, which substitute different characters, add new levels, change the game’s graphics, sound, or thematic elements, etc. — hence perpetuating an unofficial serialization process that runs parallel to Nintendo’s own official game series, and forming the basis of communal formations through more or less direct manipulation of computer code (in the form of assembly language, hex code, or mediated through specialized software platforms, including emulators and tools for altering the game). In other words, the social superstructure of serial collectivity gets inscribed directly into the infra-ludic level of code, leaving traces that can be studied for a better understanding of digital seriality.

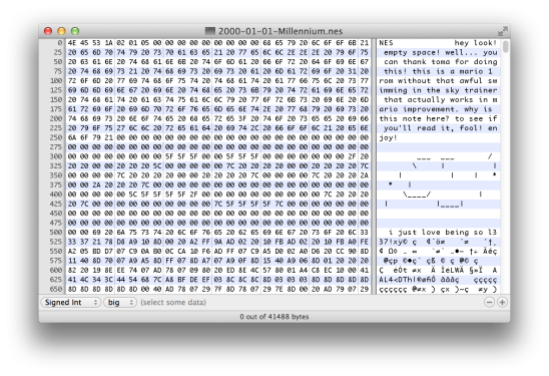

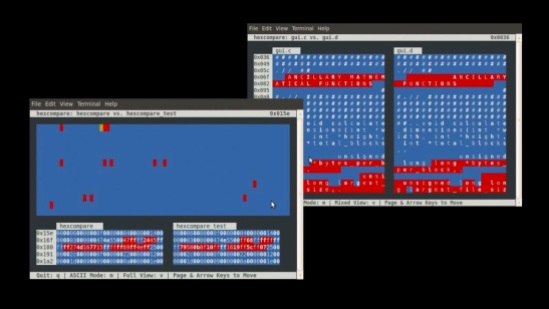

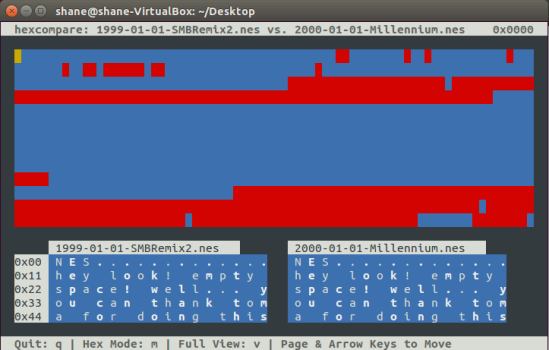

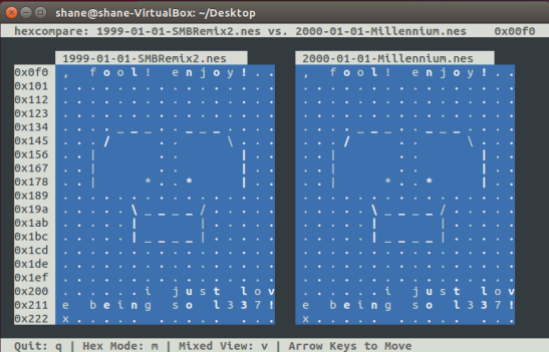

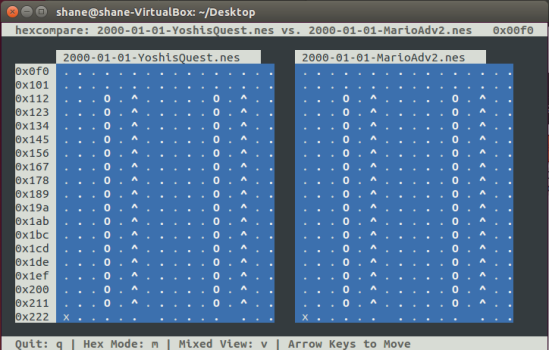

But how should we study them? Even this relatively small sample is still quite large by the standards of a traditional, close reading-based criticism. What would we be looking for anyway? The various mods are distributed as patches (.ips files) which have to be applied to a ROM file of the original game; the patches are just instruction files indicating how the game’s code is to be modified by the computer. As such, the patch files can be seen, rather abstractly, as crystallizations of the serialization process: if repetition + variation is the formal core of seriality, the patches are the records of pure variation, waiting to be plugged back into the framework of the game (the repeating element). But when we do plug it back in, then what? We can play the game in an emulator, and certainly it would be interesting — but extremely time-consuming — to compare them all in terms of visual appearance, gameplay, and interface. Or we can open the modified game file in a hex editor, in which case we might get lucky and find an interesting trace of the serialization process, such as the following:

Similar to Super Star Trek with its REM comments documenting its own serial and collective genesis, here we find an embedded infratext in the hexcode of “Millennium Mario,” a mod by an unknown hacker reportedly dating back to January 1, 2000. Note, in particular, the reference to a fellow modder, “toma,” the self-glorifying “1337” comment, and the skewed ASCII art — all signs of a community of serialization operating at a level subterranean to gameplay. But this example also demonstrates the need for a more systematic approach — as well as the obstacles to systematicity, for at stake here is not just code but also the software we use to access it and other “parergodic” elements, including even the display window size or “view” settings of the hex editor:

In a sense, this might be seen as a first demonstration of the importance of visualization not only in the communication of results but in the constitution of research objects! In any case, it clearly establishes the need to think carefully about what it is, precisely, that we are studying: serialization is not imprinted clearly and legibly in the code, but is distributed in the interfaces of software and hardware, gameplay and modification, code and community.

Again, I follow Mark Marino’s conception of critical code studies, particularly with respect to his broad understanding of the object of study:

What can be interpreted?

Everything. The code, the documentation, the comments, the structures — all will be open to interpretation. Greater understanding of (and access to) these elements will help critics build complex readings. In “A Box Darkly,” discussed below, Nick Montfort and Michael Mateas counter Cayley’s claim of the necessity for executability, by acknowledging that code can be written for programs that will never be executed. Within CCS, if code is part of the program or a paratext (understood broadly), it contributes to meaning. I would also include interpretations of markup languages and scripts, as extensions of code. Within the code, there will be the actual symbols but also, more broadly, procedures, structures, and gestures. There will be paradigmatic choices made in the construction of the program, methods chosen over others and connotations.

In addition to symbols and characters in the program files themselves, paratextual features will also be important for informed readers. The history of the program, the author, the programming language, the genre, the funding source for the research and development (be it military, industrial, entertainment, or other), all shape meaning, although any one reading might emphasize just a few of these aspects. The goal need not be code analysis for code’s sake, but analyzing code to better understand programs and the networks of other programs and humans they interact with, organize, represent, manipulate, transform, and otherwise engage.

But, especially when we’re dealing with a large set of serialized texts and paratexts, this expansion of code and the attendant proliferation of data exacerbates our methodological problems. How are we to conduct a “critical hermeneutics” of the binary files, their accompanying README files, the ROMhacking website, and its extensive database — all of which contain information relevant to an assessment of the multi-layered processes of digital seriality? It is here, I suggest, that CCS can profit from combination with DH methods.

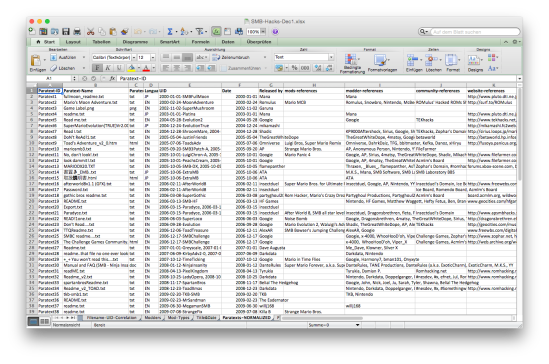

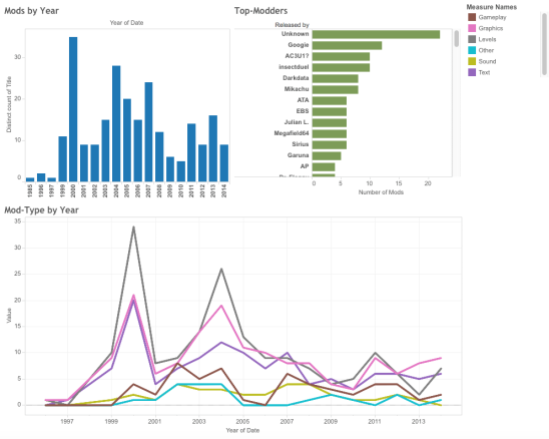

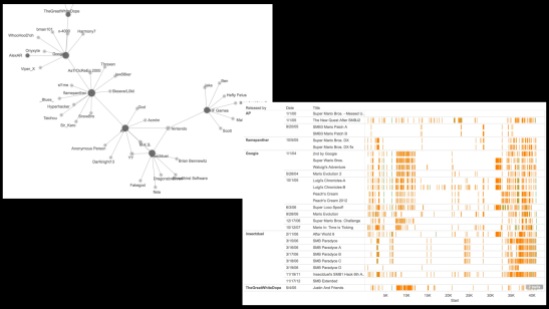

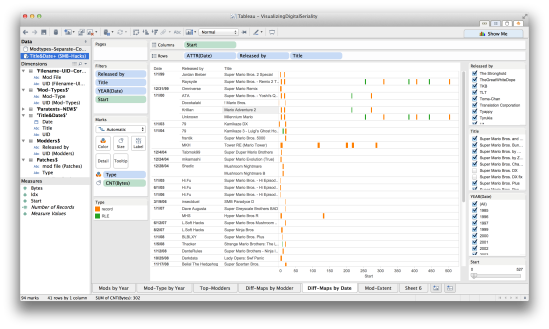

The first step in my attempt to do so was to mine data from the ROMhacking website and paratexts distributed with the patches and to create a spreadsheet with relevant metadata (you can download the Excel file here: SMB-Hacks-Dec1). On this basis, I began trying to analyze and visualize the data with Tableau. But while this yielded some basic information that might be relevant for assessing the serial community (e.g. the number of mods produced each year, including upward and downward trends; a list of the top modders in the community; and a look at trends in the types of mods/hacks being produced), the visualizations themselves were not very interesting or informative on their own (click on the image below for an interactive version):

How could this high-level metadata be coordinated with and brought to bear on the code-level serialization processes that we saw in the hexcode above? In looking for an answer, it became clear that I would have to find a way to collect some data about the code. The mods, themselves basically just “diff” files, could be opened and compared with the “diff” function that powers a lot of DH-based textual analysis (for example, with juxta), but the hexadecimal code that we can access here — and the sheer amount of it in each modded game, which consists of over 42000 bytes — is not particularly conducive to analysis with such tools. Many existing hex editors also include a “diff” analysis, but it occurred to me that it would be more desirable to have a graphical display of differences between the files in order to see the changes at a glance. My thinking here was inspired by hexcompare, a Linux-based visual diff program for quickly visualizing the differences between two binary programs:

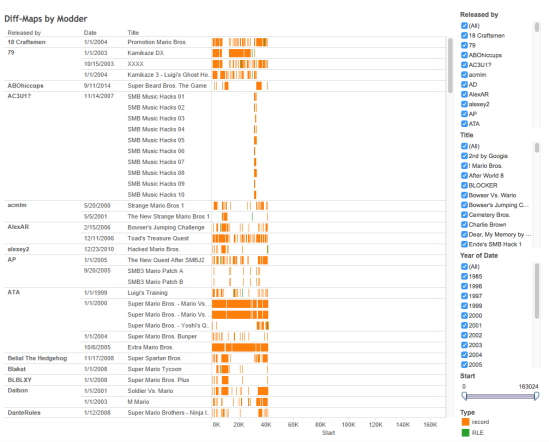

However, the comparison here is restricted to local use on a Linux machine, and it only considers two files at a time. If this type of analysis is to be of any use for seriality studies, it will have to assess a much larger set of files and/or automate the comparison process. This is where Eric Monson and Angela Zoss from Visualization & Information Services at Duke University came in and helped me to develop an alternative approach. Eric Monson wrote a script that analyzes the mod patch files and records the basic “diff” information they contain: the address or offset at which they instruct the computer to modify the game file, as well as the number of bytes that they instruct it to write. With this information (also recorded in the Excel file linked to above), a much more useful and interactive visualization can be created with Tableau (click for an interactive version):

Here, Gannt charts are used to represent the size and location of changes that a given mod makes to the original Mario game; it is possible to see a large number of these mods at a single glance, to filter them by year, by modder, by title, or even size (some mods expand the original code), etc., and in this way we can begin to see patterns emerging. Thus, we bring a sort of “distant reading” to the level of code, combining DH and CCS. (Contrast this approach with Marino’s 2006 call to “make the code the text,” which despite his broad understanding of code and acknowledgement that software/hardware and text/paratext distinctions are non-absolute, was still basically geared towards a conception of CCS that encouraged critical engagements of the “close-reading” type. As I have argued, however, researching seriality in particular requires that we oscillate between big-picture and micro-level analyses, between distant readings of larger trends and developments and detailed comparisons between individual elements or episodes in the serial chain.)

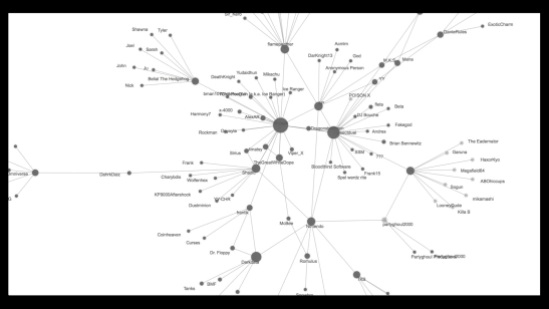

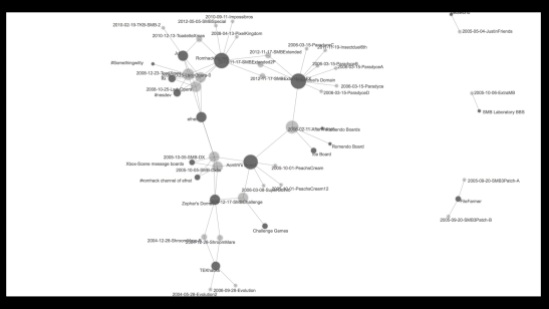

But to complete this approach, we still need to correlate this code-based data with the social level of online modding communities. For this purpose, I used Palladio (a tool explicitly designed for DH work by the Humanities + Design lab at Stanford) to graph networks on the basis of metadata contained in Readme.txt files.

Here, I have mapped the references (“shout-outs,” etc) that modders made to one another in these paratexts, thus revealing a picture of digital seriality as an imagined community of modders.

Here, on the other hand, I have mapped references from paratextual materials associated with individual mods to various online communities that have come and gone over the years. We see early references to the defunct TEKhacks, by way of Zophar’s Domain, Acmlm’s and Insectduel’s boards, with more recent references to Romhacking.net, the most recent community site and the one that I am studying here.

As an example of how the social network and code-level analyses might be correlated, here I’ve filtered the network graph to show only those modders who refer in their paratexts to Super Mario Bros. 3 (hence bringing inter-ludic seriality to bear on their para- and infra-ludic interventions). The resulting graph reveals a small network of actors whose serializing activity involves mixing and referencing between SMB1 and SMB3, as well as between each other. The Tableau screenshot on the right then selects just these modders and reveals possible similarities and sites of serialization (for closer scrutiny with hexcompare or tools derived from the modding community itself). For example, we find that the modder AP’s SMB3-inspired patches from September 2005 and flamepanther’s SMB DX patches from Oct 2005 exhibit traces of possible overlap that deserve to be looked at in detail. The modder insectduel’s After World 8 (a mod that is referenced by many in the scene) from February 2006 shares large blocks around 31000-32000 bytes with many of the prolific modder Googie’s mods (which themselves seem to exhibit a characteristic signature) from 2004-2006. Of course, recognizing these patterns is just the beginning of inquiry, but at least it is a beginning. From here, we still have to resort to “close reading” techniques and to tools that are not conducive to a broad view; more integrated toolsets remain to be developed. Nevertheless, these methods do seem promising as a way of directing research, showing us where to look in greater depth, and revealing trends and points of contact that would otherwise remain invisible.

Finally, by way of conclusion and to demonstrate what some of this more detailed work looks like, I’d like to return to the “Millennium Mario” mod I considered briefly above. As we saw, there was an interesting infratextual shoutout and some ASCII art in the opening section of the hexcode. With Tableau, we can filter the “diff” view to display only those mods that exhibit changes in the first 500 bytes of code, and to map that section of code in greater resolution (this is done with the slider in the bottom right corner, marked “Start” — referring to the byte count at which a change in the game starts):

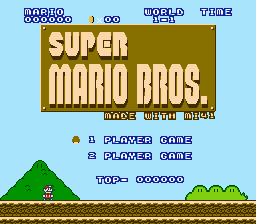

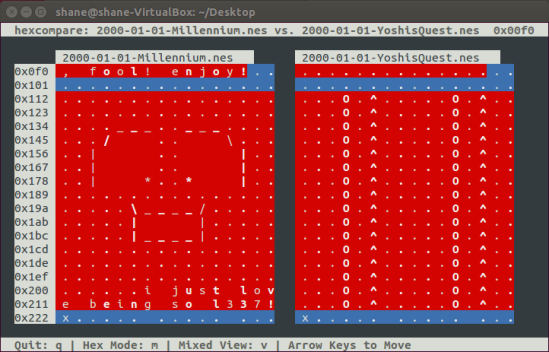

Here we find two distinctive (visual) matches: viz. between “Millennium Mario” and Raysyde’s “Super Mario Bros. – Remix 2” from 1999, and between ATA’s “Super Mario Bros. – Yoshi’s Quest” and Krillian’s “Mario Adventure 2,” both from 2000. The latter two mods, while clearly different from the former two, also exhibit some overlap in the changes made to the first 20 or so bytes, so it will be interesting to compare them as well.

Now we can use hexcompare for finer analysis — i.e. to determine if the content of the changed addresses is also identical (the visual match only tells us that something has been changed in the same place, not whether the same change has been made there).

Here we find that Raysyde’s “Super Mario Bros. – Remix 2” does in fact display the same changes in the opening bytes, including the reference to “toma” and the ASCII art. This then is a clear indication of infra-ludic serialization: the borrowing, repetition, and variation of code-level work between members of the modding community. This essentially serial connection (an infra-serial link) would hardly be apparent from the level of the mods’ respective interfaces, though:

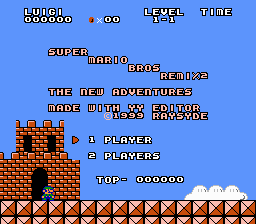

When we compare “Millennium Mario” with ATA’s “Super Mario Bros. – Yoshi’s Quest,” we find the ASCII art gone, despite the visual match in Tableau’s mapping of their “diff” indications for the opening bytes:

“Yoshi’s Quest” corresponds in this respect to Krillian’s “Mario Adventure 2”:

Thus we have another clear indication of infra-ludic serialization, which would hardly have been evident other than by means of a directed filtering of the large dataset, in conjunction with a close analysis of the underlying code.

Again, however, this is just the beginning of the analysis — or more broadly of an encounter between DH and CCS. Ideally, the dataset would be expanded beyond ROMhacking.net’s database; other online communities would be mined for data; and, above all, more integrative tools would be developed for correlating social network graphs and diff-maps, for correlating community and code. Perhaps a crowdsourced approach to some of this would be appropriate; for what it’s worth, and in case anyone is inclined to contribute, my data and the interactive Tableau charts are linked above. But the real work, I suspect, lies in building the right tools for the job, and this will clearly not be an easy task. Alas, like digital seriality itself, this is work in progress, and thus it remains work “to be continued”…

Thanks finally to Eric Monson, Angela Zoss, Victoria Szabo, Patrick LeMieux, Max Symuleski, and the participants in the Fall 2014 “Historical & Cultural Visualization Proseminar 1” at Duke University for the various sorts of help, feedback, and useful tips they offered on this project!