On November 22-23, 2013, I will be participating in the conference “Post-Cinematic Perspectives,” which is being organized by Lisa Åkervall and Chris Tedjasukmana at the Freie Universität Berlin. There’s a great line-up, as you’ll see on the conference program above. I look forward to seeing Steven Shaviro again (and hearing his talk on Spring Breakers), and to meeting all the other speakers. My talk, on the morning of the 23rd, is entitled “Nonhuman Perspectives and Discorrelated Images in Post-Cinema.” The conference is open to the public, and attendance is free.

Category: Things

Day of the Future 2013

Today is Zukunftstag (“Future Day” or “Day of the Future”) here in Germany. On this day, 5th graders go to a place of work (a corporation, a bank, a hospital, a factory, police department, etc.) instead of going to school. Today, my ten-year-old son (a.k.a. DrZombie999) came with me to the university to see what it’s like to work here. I showed him what kinds of things we do here everyday: you know, the usual things like playing video games, goofing around, and surfing YouTube…

But then we decided to get serious, and we put together the video above. Having built the world you see in the popular game Minecraft, DrZombie999 takes us on a little guided tour, which we then saved as a screencast video, edited with nonlinear editing software (where he learned how to add transitions, effects, music, etc.), posted to a brand new YouTube account, and blogged here to get the word out.

DrZombie999 promises that this is only the first in an ongoing series of videos, and he asks viewers to vote for what they’d like to see him build next (from the Lord of the Rings universe). Please leave a comment on his YouTube site if you’ve got an idea! He’ll only be taking votes for one month (until May 25, 2013)!

Conspiracies and Surveillance — In Media Res Theme Week

Over at the media commons site in media res, what promises to be a great theme week on “Conspiracies and Surveillance” has just gotten underway. All of the contributions sound exciting, and among them is one by our very own Felix Brinker, who’s up tomorrow (Tuesday, April 9) with a piece on the “logics of conspiracy” in American TV series. (And in case you missed it, make sure you check out the longer text on the topic that Felix allowed me to post here recently.)

Here’s the full lineup for the in media res theme week:

Monday, April 8, 2013 – Jason Derby (Georgia State University) presents: Scandalous Conspiracies: Making Sense of Popular Scandal Through Conspiracy

Tuesday, April 9, 2013 – Felix Brinker (Leibniz University of Hannover, Germany) presents: Contemporary American Prime-Time Television Serials and the Logics of Conspiracy

Wednesday, April 10, 2013 – Meagan Winkelman (University of Oregon) presents: Sexuality and Agency in Pop Star Conspiracy Theories

Thursday, April 11, 2013 – Perin Gurel (University of Notre Dame) presents: Transnational Conspiracy Theories and Vernacular Visual Cultures: Political Islam in Turkey and America

Friday, April 12, 2013 – Jack Bratich (Rutgers University) presents: Millions of Americans Believe Conspiracy Theories Exist

Each day’s contribution, consisting of a video clip of up to three minutes accompanied by a short essay of 300-350 words, is designed to serve as a conversation starter aimed at involving a broad audience in discussion of key topics relating to the topic of “Conspiracies and Surveillance.”

Please check out all the contributions as they go live here, and consider joining the discussion (to participate, you will need to register at in media res).

We need to verify you’re not a robot!

[View the story “We need to verify you’re not a robot!” on Storify]

Storified by Shane Denson· Sun, Mar 31 2013 09:52:32

Crazy Cameras, Discorrelated Images, and the Post-Perceptual Mediation of Post-Cinematic Affect — #SCMS13

Below you’ll find the full text of the talk I just gave at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Chicago, as part of a panel on “Post-Cinematic Affect: Theorizing Digital Movies Now” along with Therese Grisham, Steven Shaviro, and Julia Leyda — all of whom I’d like to thank for their great contributions! As always, comments are more than welcome!

Crazy Cameras, Discorrelated Images, and the Post-Perceptual Mediation of Post-Cinematic Affect

Shane Denson

I’m going to talk about crazy cameras, discorrelated images, and post-perceptual mediation as three interlinked facets of the medial ontology of post-cinematic affect. I’ll connect my observations to empirical and phenomenological developments surrounding contemporary image production and reception, but my primary interest lies in a more basic determination of affect and its mediation today. Following Bergson, affect pertains to a domain of material and “spiritual” existence constituted precisely in a gap between empirically determinate actions and reactions (or, with some modification, between the production and reception of images); affect subsists, furthermore, below the threshold of conscious experience and the intentionalities of phenomenological subjects (including the producers and viewers of media images). It is my contention that the infrastructure of life in our properly post-cinematic era has been subject to radical transformations at this level of molecular or pre-personal affect, and following Steven Shaviro I suggest that something of the nature and the stakes of these transformations can be glimpsed in our contemporary visual media.

My argument revolves around what I’m calling the “crazy cameras” of post-cinematic media, following comments by Therese Grisham in our roundtable discussion in La Furia Umana (alternatively, here): Seeking to account for the changed “function of cameras […] in the post-cinematic episteme,” Therese notes that whereas “in classical and post-classical cinema, the camera is subjective, objective, or functions to align us with a subjectivity which may lie outside the film,” there would seem to be “something altogether different” in recent movies. “For instance, it is established that in [District 9], a digital camera has shot footage broadcast as news reportage. A similar camera ‘appears’ intermittently in the film as a ‘character.’ In the scenes in which it appears, it is patently impossible in the diegesis for anyone to be there to shoot the footage. Yet, we see that camera by means of blood splattered on it, or we become aware of watching the action through a hand-held camera that intrudes suddenly without any rationale either diegetically or aesthetically. Similarly, but differently as well, in Melancholia, we suddenly begin to view the action through a ‘crazy’ hand-held camera, at once something other than just an intrusive exercise in belated Dogme 95 aesthetics and more than any character’s POV […].”

What it is, precisely, that makes these cameras “crazy,” or opaque to rational thought? My answer, in short, is that post-cinematic cameras – by which I mean a range of imaging apparatuses, both physical and virtual – seem not to know their place with respect to the separation of diegetic and nondiegetic planes of reality; these cameras therefore fail to situate viewers in a consistently and coherently designated spectating-position. More generally, they deviate from the perceptual norms established by human embodiment – the baseline physics engine, if you will, at the root of classical continuity principles, which in order to integrate or suture psychical subjectivities into diegetic/narrative constructs had to respect above all the spatial parameters of embodied orientation and locomotion (even if they did so in an abstract, normalizing form distinct from the real diversity of concrete body instantiations). Breaking with these norms results in what I call the discorrelation of post-cinematic images from human perception.

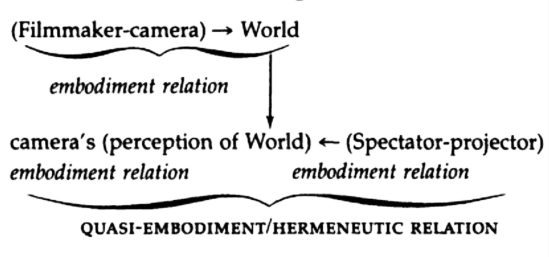

With the idea of discorrelation, I aim to describe an event that first announces itself negatively, as a phenomenological disconnect between viewing subjects and the object-images they view. In her now-classic phenomenology of filmic experience, The Address of the Eye, Vivian Sobchack theorized a correlation – or structural homology – between spectators’ embodied perceptual capacities and those of film’s own apparatic “body,” which engages viewers in a dialogical exploration of perceptual exchange; cinematic expression or communication, accordingly, was seen to be predicated on an analogical basis according to which the subject and object positions of film and viewer are dialectically transposable.

But, according to Sobchack, this basic perceptual correlation is endangered by new, or “postcinematic” media (as she was already calling them in 1992), which disrupt the commutative interchanges of perspective upon which filmic experience depends for its meaningfulness. With the tools Sobchack borrows from philosopher of technology Don Ihde, we can make a first approach to the “crazy” quality of post-cinematic cameras and the discorrelation of their images.

Take the example of the digitally simulated lens flare, featured ostentatiously in recent superhero films like Green Lantern or the Ghost Rider sequel directed by Neveldine and Taylor, who brag that their use of it breaks all the rules of what you can and can’t do in 3D. Beyond the stylistically questionable matter of this excess, a phenomenological analysis reveals significant paradoxes at the heart of the CGI lens flare. On the one hand, the lens flare encourages what Ihde calls an “embodiment relation” to the virtual camera: by simulating the material interplay of a lens and a light source, the lens flare emphasizes the plastic reality of “pro-filmic” CGI objects; the virtual camera itself is to this extent grafted onto the subjective pole of the intentional relation, “embodied” in a sort of phenomenological symbiosis that channels perception towards the objects of our visual attention. On the other hand, however, the lens flare draws attention to itself and highlights the images’ artificiality by emulating (and foregrounding the emulation of) the material presence of a camera. To this extent, the camera is rendered quasi-objective, and it instantiates what Ihde calls a “hermeneutic relation”: we look at the camera rather than just through it, and we interpret it as a sign or token of “realisticness.” The paradox here, which consists in the realism-constituting and -problematizing undecidability of the virtual camera’s relation to the diegesis – where the “reality” of this realism is conceived as thoroughly mediated, the product of a simulated physical camera rather than defined as the hallmark of embodied perceptual immediacy – points to a more basic problem: namely, to a transformation of mediation itself in the post-cinematic era. That is, the undecidable place of the mediating apparatus, the camera’s apparently simultaneous occupation of both subjective and objective positions within the noetic relation that it enables between viewers and the film, is symptomatic of a more general destabilization of phenomenological subject- and object-positions in relation to the expanded affective realm of post-cinematic mediation. Computational, ergodic, and processual in nature, media in this mode operate on a level that is categorically beyond the purview of perception, perspective, or intentionality. Phenomenological analysis can therefore provide only a negative determination “from the outside”: it can help us to identify moments of dysfunction or disconnection, but it can offer no positive characterization of the “molecular” changes occasioning them. Thus, for example, CGI and digital cameras do not just sever the ties of indexicality that characterized analogue cinematography (an epistemological or phenomenological claim); they also render images themselves fundamentally processual, thus displacing the film-as-object-of-perception and uprooting the spectator-as-perceiving-subject – in effect, enveloping both in an epistemologically indeterminate but materially quite real and concrete field of affective relation. Mediation, I suggest, can no longer be situated neatly between the poles of subject and object, as it swells with processual affectivity to engulf both.

Compare, in this connection, film critic Jim Emerson’s statement in response to the debates over so-called “chaos cinema”: “It seems to me that these movies are attempting a kind of shortcut to the viewer’s autonomic nervous system, providing direct stimulus to generate excitement rather than simulate any comprehensible experience. In that sense, they’re more like drugs that (ostensibly) trigger the release of adrenaline or dopamine while bypassing the middleman, that part of the brain that interprets real or imagined situations and then generates appropriate emotional/physiological responses to them. The reason they don’t work for many of us is because, in reality, they give us nothing to respond to – just a blur of incomprehensible images and sounds, without spatial context or allowing for emotional investment.” Now, I want to distance myself from what appears to be a blanket disapproval of such stimulation, but I quote Emerson’s statement here because I think it neatly identifies the link between a direct affective appeal and the essentially post-phenomenological dissolution of perceptual objects. Taken seriously, though, this link marks the crux of a transformation in the ontology of media, the point of passage from cinematic to post-cinematic media. Whereas the former operate on the “molar” scale of perceptual intentionality, the latter operate on the “molecular” scale of sub-perceptual and pre-personal embodiment, potentially transforming the material basis of subjectivity in a way that’s unaccountable for in traditional phenomenological terms. But how do we account for this transformative power of post-cinematic media, short of simply reducing it (as it would appear Emerson tends to do) to a narrowly positivistic conception of physiological impact? It is helpful here to turn to Maurizio Lazzarato’s reflections on the affective dimension of video and to Mark Hansen’s expansions of these ideas with respect to computational and what he calls “atmospheric” media.

According to Lazzarato, the video camera captures time itself, the splitting of time at every instant, hence opening the gap between perception and action where affect (in Bergson’s metaphysics) resides. Because it no longer merely traces objects mechanically and fixes them as discrete photographic entities, but instead generates its images directly out of the flux of sub-perceptual matter, which it processes on the fly in the space of a microtemporal duration, the video camera marks a revolutionary transformation in the technical organization of time. The mediating technology itself becomes an active locus of molecular change: a Bergsonian body qua center of indetermination, a gap of affectivity between passive receptivity and its passage into action. The camera imitates the process by which our own pre-personal bodies synthesize the passage from molecular to molar, replicating the very process by which signal patterns are selected from the flux and made to coalesce into determinate images that can be incorporated into an emergent subjectivity. This dilation of affect, which characterizes not only video but also computational processes like the rendering of digital images (which is always done on the fly), marks the basic condition of the post-cinematic camera, the positive underside of what presents itself externally as a discorrelating incommensurability with respect to molar perception. As Mark Hansen has argued, the microtemporal scale at which computational media operate enables them to modulate the temporal and affective flows of life and to affect us directly at the level of our pre-personal embodiment. In this respect, properly post-cinematic cameras, which include video and digital imaging devices of all sorts, have a direct line to our innermost processes of becoming-in-time, and they are therefore capable of informing the political life of the collective by flowing into the “general intellect” at the heart of immaterial or affective labor.

The Paranormal Activity series makes these claims palpable through its experimentation with various modes and dimensions of post-perceptual, affective mediation. After using hand-held video cameras in PA1 and closed-circuit home-surveillance cameras in PA2, and following a flashback by way of old VHS tapes in PA3, the latest installment intensifies its predecessors’ estrangement of the camera from cinematic and ultimately human perceptual norms by implementing computational imaging processes for its strategic manipulations of spectatorial affect. In particular, PA4 uses laptop- and smartphone-based video chat and the Xbox’s Kinect motion control system to mediate between diegetic and spectatorial shocks and to regulate the corporeal rhythms and intensities of suspenseful contraction and release that define the temporal/affective quality of the movie. Especially the Kinect technology, itself a crazy binocular camera that emits a matrix of infrared dots to map bodies and spaces and integrate them algorithmically into computational/ergodic game spaces, marks the discorrelation of computational from human perception: the dot matrix, which is featured extensively in the film, is invisible to the human eye; the effect is only made possible through a video camera’s night vision mode – part of the post-perceptual sensibility of the video camera that distinguishes it from the cinema camera. The film (and the series more generally) is thus a perfect illustration for the affective impact and bypassing of cognitive (and narrative) interest through video and computational imaging devices. In an interview, (co)director Henry Joost says the use of the Kinect, inspired by a YouTube video demonstrating the effect, was a logical choice for the series, commenting: “I think it’s very ‘Paranormal Activity’ because it’s like, there’s this stuff going on in the house that you can’t see.” Indeed, the effect highlights all the computational and video-sensory activity going on around us all the time, completely discorrelated from human perception, but very much involved in the temporal and affective vicissitudes of our daily lives through the many cameras and screens surrounding us and involved in every aspect of the progressively indistinct realms of our work and play. Ultimately, PA4 points toward the uncanny qualities of contemporary media, which following Mark Hansen have ceased to be contained in discrete apparatic packages and have become diffusely “atmospheric.”

This goes in particular for the post-cinematic camera, which has shed the perceptually commensurate “body” that ensured communication on Sobchack’s model and which, beyond video, is no longer even required to have a material lens. This does not mean the camera has become somehow immaterial, but today the conception of the camera should perhaps be expanded: consider how all processes of digital image rendering, whether in digital film production or simply in computer-based playback, are involved in the same on-the-fly molecular processes through which the video camera can be seen to trace the affective synthesis of images from flux. Unhinged from traditional conceptions and instantiations, post-cinematic cameras are defined precisely by the confusion or indistinction of recording, rendering, and screening devices or instances. In this respect, the “smart TV” becomes the exemplary post-cinematic camera (an uncanny domestic “room” composed of smooth, computational space): it executes microtemporal processes ranging from compression/decompression, artifact suppression, resolution upscaling, aspect-ratio transformation, motion-smoothing image interpolation, and on-the-fly 2D to 3D conversion. Marking a further expansion of the video camera’s artificial affect-gap, the smart TV and the computational processes of image modulation that it performs bring the perceptual and actional capacities of cinema – its receptive camera and projective screening apparatuses – back together in a post-cinematic counterpart to the early Cinématographe, equipped now with an affective density that uncannily parallels our own. We don’t usually think of our screens as cameras, but that’s precisely what smart TVs and computational display devices in fact are: each screening of a (digital or digitized) “film” becomes in fact a re-filming of it, as the smart TV generates millions of original images, more than the original film itself – images unanticipated by the filmmaker and not contained in the source material. To “render” the film computationally is in fact to offer an original rendition of it, never before performed, and hence to re-produce the film through a decidedly post-cinematic camera. This production of unanticipated and unanticipatable images renders such devices strangely vibrant, uncanny – very much in the sense exploited by Paranormal Activity. The dilation of affect, which introduces a temporal gap of hesitation or delay between perception (or recording) and action (or playback), amounts to a modeling or enactment of the indetermination of bodily affect through which time is generated, and by which (in Bergson’s system) life is defined. A negative view sees only the severing of the images’ indexical relations to world, hence turning all digital image production and screening into animation, not categorically different from the virtual lens flares discussed earlier. But in the end, the ubiquity of “animation” that is introduced through digital rendering processes should perhaps be taken literally, as the artificial creation of (something like) life, itself equivalent with the gap of affectivity, or the production of duration through the delay of causal-mechanical stimulus-response circuits; the interruption of photographic indexicality through digital processing is thus the introduction of duration = affect = life. Discorrelated images, in this respect, are autonomous, quasi-living images in Bergson’s sense, having transcended the mechanicity that previously kept them subservient to human perception. Like the unmotivated cameras of D9 and Melancholia, post-cinematic cameras generally have become “something altogether different,” as Therese put it: apparently crazy, because discorrelated from the molar perspectives of phenomenal subjects and objects, cameras now mediate post-perceptual flows and confront us everywhere with their own affective indeterminacy.

Serial Bodies

Below you’ll find the full text of the talk I delivered today at the “It’s Not Television” conference in Frankfurt. Unfortunately, I had to leave the conference early, so I didn’t have time to discuss the talk in any detail following the brief Q & A. I’m hoping, then, that some of those people who expressed an interest in discussing my ideas and proposals further might take the opportunity to comment here. And, of course, even if you weren’t there today, comments on this early-stage work are very welcome!

Serial Bodies: Corporeal Engagement in Long-Form Serial Television

Shane Denson

In this talk, I want to consider the possibility and the purpose of an “affective turn” in television studies. I’ll try to explain what such a “turn,” or refocusing of scholarly attention, might entail, and I’ll consider some of the grounds for making such a move.

First of all, the “affective turn” as I’m using the term describes developments going on in various disciplines, including philosophy and media and cultural theory, since about the 1990s. Following theorists such as Deleuze and Guattari, Steven Shaviro, and Brian Massumi, the “affect” in question here refers to a domain of pre-personal feelings, not subjective emotions but raw intensities that transpire below the threshold of consciousness, as functions and correlates of non-voluntary processes: for example, the not-quite-conscious sensations associated with visceral, proprioceptive, and endocrinological changes in one’s overall body-state. Thus, affects are diffuse material forces and sensations, whereas emotions are their more narrowly focused correlates; affects precede consciousness and envelop the mind, while emotions can be seen to involve the subjective “capture” of affect, the yoking of affect to consciousness, or the filtering and processing that takes place when pre-reflective affect becomes available to reflective conscious experience. Theory and criticism undertaken in the wake of an affective turn seek to uncover the material and cultural efficacy of affect prior to this filtering.

But why would television scholars want to make this turn towards a subterranean domain of pre-personal affect? Briefly, I want to propose that an affective turn would help to highlight the richly material parameters of the televisual experience, to focus attention on embodied interfaces and non-cognitive transfers, thus providing a counterpoint to the dominant celebration of cognitive effort in recent television studies. In other words, the context for an affect-oriented intervention is the tendency, widespread in popular and scholarly accounts alike of recent television, to intellectualize the medium, to focus on complex narrative structures in an effort to redeem TV from long-standing prejudices and stereotypes that cast the bulk of programming as culturally inferior trash produced for a passive, undiscriminating, and distracted mass audience. Foregrounding the emergence of a new televisual “quality,” many recent critical approaches have focused particularly on contemporary serial television’s demanding textual forms, which seek to engage viewers with complex puzzles and intricately orchestrated plot developments – thus breaking with the formulaic repetition characteristic of simple episodic programs and providing mental stimulation in exchange for viewers’ long-term investments of attention. As early as the 1980s, the advocacy group Viewers for Quality Television had defined “quality” in the following terms: “A quality series enlightens, enriches, challenges, involves and confronts. It dares to take risks, it’s honest and illuminating, it appeals to the intellect and touches the emotions. It requires concentration and attention, and it provokes thought.” In short, quality TV does what good literature is supposed to do, namely: to engage the viewer/reader and make him or her think. And popular criticism has continued to pursue this tack in the effort to make television respectable, e.g. by comparing newer series to the nineteenth century novel – The Wire, for example, has been called “a Balzac for our time”, thereby suggesting that this paradigmatically complex series distinguishes itself by a heady sort of appeal that rewards the sophisticated viewer. Steven Johnson has famously claimed that such complex television provides its viewers with what he calls a “cognitive workout.” And Jason Mittell, who has probably done more than any of these people to explore the mechanics of complexity, has noted the way complex series reward viewers who assume the role of “amateur narratologists.”

Clearly, the critical reappraisal of the medium and its implied viewer is not without foundation, as it speaks to very real changes in television programming in the wake of industrial, technological, and cultural shifts. Over the past ten years or so, there has indeed been an unprecedented flowering of programs that would seem to encourage active and intellectually engaged viewing. At the same time, though, graphic scenes of sex and violence proliferate across contemporary television series, including shows widely valued for their sophisticated cognitive demands. In particular, bodies are now routinely put on display, violated, tortured, dissected, and ripped apart in ways unimaginable on TV screens just a decade ago. I want to be clear that I don’t think this in any way invalidates theories and analyses that foreground the cognitive appeals of narratively complex TV. But this explosion of body images – including images of bodies exploding – does, I think, challenge such approaches to reconcile intellectual and more broadly affective and body-based appeals. By advocating an affective turn, a turn towards a diffuse, inarticulate field of pre-personal affect, I am not urging a turn away from consciousness or a regressive turn back to the view of an unrefined, unintellectual viewer. Instead, I am asking for more thought about how cognitive and affective appeals coexist today, and specifically about how they might be seen to work in tandem to maintain the momentum of contemporary television’s serial trajectories.

Seriality is the key word here: seriality is one of the things that’s illuminated particularly well by broadly cognitivist and narratological approaches, and it’s seriality, I think, that marks the real challenge for an affective turn in TV studies. Consider Brian Massumi’s definition of affect as “a suspension of action-reaction circuits and linear temporality in a sink of what might be called ‘passion,’ to distinguish it both from passivity and activity” (28). This conception, which Massumi associates with the thinking of Baruch Spinoza, accords also with Henri Bergson’s notion of affect as “that part or aspect of the inside of our bodies which mix with the image of external bodies” (Matter and Memory 60). And the Bergsonian image of the body as a “center of indetermination,” where affect is an intensity experienced in a state of “suspension,” outside of linear time and the empirical determinateness of forward-oriented action, corresponds to a major emphasis in film theory conducted in the wake of the affective turn – namely, a focus on privileged but fleeting moments, when narrative continuity breaks down and the images on the screen resonate materially, unthinkingly, or pre-reflectively with the viewer’s autoaffective sensations. Such moments figure prominently in what Linda Williams calls the “body genres” of melodrama, horror, and pornography – genres in which images on screen are mobilized to arouse pity, fear, or desire directly in the body of the viewer. In his now classic study, The Cinematic Body, Steven Shaviro explores extreme cases like the self-reflexive attunement between gory images of zombies dismembering and disgorging on-screen characters, on the one hand, and the embodied spectator affected viscerally by these images on the other. But these are moments of caesura, when narrative and discursive significance dissolves and gives way to an “abject” experience of material plenitude prior to its parceling out into subject-object roles and relations. These displaced or “utopic” moments, dilated experientially to allow for a poetic sort of tarrying alongside images, are of course already exceptional in narrative cinema, but they must seem even more clearly at odds with the vectors of serial continuation that pull television viewers from one episode to the next, engrossing them in a story-world and concerning them with the lives of its characters week after week, over the course of several seasons.

So if television studies is to make an affective turn, it will have to account for the medial differences between long-form serial television and closed-form film, and it will have to distinguish the role of affect in each. One place to start with this comparison might be the self-reflexive “operational aesthetic” that Jason Mittell, following Neil Harris’s work on P.T. Barnum, has attributed to contemporary serial television as one of its central mechanisms. For Mittell, the operational aesthetic is related to the cognitive operation of tracing and taking pleasure in the complexities of narrative twists. At stake is an enjoyment not only of the story told but also of the manner of its telling, and the operational aesthetic involves the viewer in what might be described as the recursive pleasure of recognizing a series’ own recognition of the complexity of its narration. But if television’s “narrative special effects,” as Mittell calls them, can be explained in terms of an operational aesthetic, it’s important to note that this mode of engagement has also been attributed to closed-form film to explain the appeal of special effects of the ordinary, primarily visual and non-narrative, sort. Tom Gunning has applied the term “operational aesthetic” to the body-gag spectacles of slapstick. In this view, Charlie Chaplin’s or Buster Keaton’s body gets implemented as a thing-like mechanism in a larger system of things, and the spectator takes pleasure in tracing the causal dynamics of the system, which is in a sense also the system of cinematic images itself; the cinema in turn reveals itself as a complex (Rube Goldberg-type) contraption for the transfer of material intensities from one body – Chaplin’s or Keaton’s – to another – my own, as the latter is affected physically and compelled to laugh. Similarly self-reflexive mechanisms are at work in sci-fi and horror films, where visual and visceral spectacles interrupt narrative flow and bedazzle or shock with an operational appeal to the body rather than the brain. Monumental explosions, monstrous sights flashed on the screen without warning, and show-stopping effects seek in part to bypass the brain and imprint themselves in the manner of the physiological Chockwirkung that Walter Benjamin took to be central to the filmic medium.

But is this corporeal sort of self-reflexivity, an operational aesthetic that arouses the body more than the brain, possible in long-form serial television? And, if so, can it be a central component of televisual seriality, a motor of serial development, or must it remain a mere side-show in a medium dependent upon the forward momentum of narrativity?

As I noted before, there is certainly no shortage of body spectacles on contemporary television, and they seem in many ways to function like the cinematic spectacles I’ve been describing. Procedural, or what might more properly be called operational, forensic shows likes CSI or Bones, for example, resemble science-fiction film in their showcasing of technological processes – processes that are anchored in diegetic techniques and technologies but that serve to foreground medial technologies of visualization. These displays serve, like the special effects of science-fiction film, more to impress the viewer than to advance the story. Significantly, such digressive forensic displays revolve around bodies and their imbrications with medial technologies: corpses are subjected to analytical methods that issue not in cognitive but in visual and media-technological spectacles, thus providing the spectator with an affectively potent – but narratively rather pointless – formula that gets repeated week after week. The technological probing of bodies onscreen thus speaks to and motivates a doubling of the viewing body’s own technological interface with the television screen – the material site of affective transfer, which is crucially at stake in these biotechnical displays. A show like Grey’s Anatomy similarly problematizes the integrity of bodies and sets them in relation to technologies, both medical and medial, in order to establish an affective circuit between bodies onscreen and off. Bodies in pain, bodies injured, impaled, injected, or incised, bones sawed, organs exposed and removed: all of these things have their place in a narrative, but they also maintain an excessive autonomy as images, establishing in this way a relay between an affective awareness of one’s own embodiment and an emotional engrossment in a melodramatic story.

And while these shows may tend toward the episodic or the formulaic, their employment of body spectacles might be seen to illuminate a range of contemporary television, including shows widely recognized as qualitatively complex. Premium cable shows like Nip/Tuck, Six Feet Under, Dexter, or Californication, for example, revolve around a variety of corporeal explorations. And a series like True Blood manages to combine all three of Linda Williams’s “body genres” into a hybrid mix of soft-porn, horror, and melodrama. The Walking Dead positively obsesses over its media-technological ability to generate graphic images of all states of bodily decay, thus offering a series of visual and visceral challenges to the viewer that run parallel to and punctuate the story’s unfolding. And even a starkly serialized and celebrated complex show like Breaking Bad activates these mechanisms when it visualizes a scene of bodily destruction like this one:

Here, there is a properly visual appeal, a showcasing of the image that involves the viewer by activating a sense of one’s own corporeal fragility – thus staging a deeply existential demonstration of physical vulnerability that culminates, and momentarily negates, all the narrative investment and development of character that has led up to this point. In other words, the affective force of this moment far exceeds its diegetic and medial temporality; with Massumi, we might say the image occasions “a suspension of action-reaction circuits and linear temporality in a sink of […] ‘passion’” or immersive involvement. But, I suggest, the scene demonstrates a synergistic or contrapuntal rather than strictly oppositional relation between narrative development and affective depth. The image of the exploded face retains a visual and affective singularity, an excess over and above the storyline in which it’s embedded, but its evocation of the viewer’s own delicate corporeality resonates as well with the series’ overall narrative focus on a protagonist whose body is under attack by cancer.

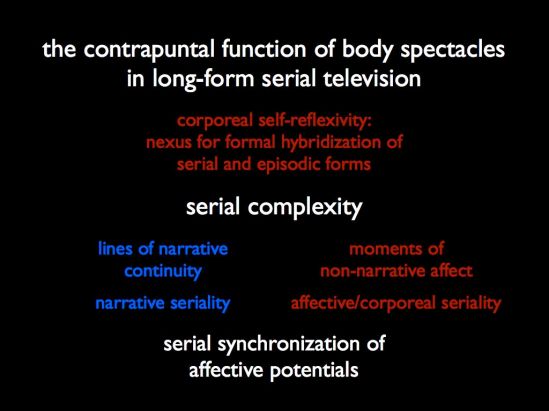

Finally, to generalize from these examples and wager a hypothesis about the contrapuntal function of such body spectacles in contemporary long-form serial television: I suggest that corporeal self-reflexivity, or the establishment of affective circuits by graphically opening up bodies for destructive, clinical, or sexual purposes, serves as a nexus for the formal hybridization of serial and episodic forms that Mittell makes central to his conception of narrative complexity. Not, of course, the nexus, but a nexus: in other words, a site where a certain sort of formal experimentation takes place, leading to an alternative form of “serially complex television” that activates an “operational aesthetic” for cognitive and corporeal means, in the process intensifying viewers’ investment in narrative developments by imbuing them with affective depth. I speak intentionally of “serial complexity” rather than “narrative complexity,” in order to account for the contrapuntal interplay between lines of narrative continuity on the one hand and moments of non-narrative affect on the other; by standing outside of series’ narrative temporalities, the latter moments punctuate continuity with discontinuity, but they also harbor the potential to establish an alternative seriality of their own, one that runs parallel to narrative development; this is an affective and corporeally registered seriality established through the repetition and variation of such poignant moments and images. Scenarios of the body-genre type serve then as fulcrum points for alternating between ongoing serial arcs and more episodically ritualistic engagements with affectively intense but narratively vacuous states of being: arousal by sexualized images, for example, or being moved to tears by highly melodramatic sequences (like the ritualized climaxes of Grey’s Anatomy, which employ music video techniques for a literally melodramatic presentation of bodily triumphs and defeats), or being shaken or disturbed by brutal violence and body horror (which can be occasioned by vampires, zombies, gladiators, serial-killers, or even health-care givers).

At stake, then, in television studies’ affective turn is the discovery of a broad, material site of serial complexity, of a nexus where shifts occur between serial and episodic forms or between repetition and variation, serially modulated through alternating appeals to cognitive effort and to bodily stimulation. By engineering self-reflexive feedback loops between onscreen body spectacles and the bodily sensitivities of offscreen viewers, contemporary series cement strong affective bonds between their viewers and the very form of complex seriality – with its shifting of gears and contrapuntal rhythms internalized at a deep, sub-cognitive level as the rhythms of one’s own body. Engagement with form thus becomes the embodiment of temporal vicissitudes that are as much those of the show as they are the flowing time of the spectator’s own affective life. At stake is a sort of serial synchronization of affective potentials, over and above (or perhaps deep below) the cognitive recognition of formal complexity. Such affective interfaces materially support and encourage mental engagements with narrative developments, but they do so by cultivating deep material resonances that, at the farthest extreme, institute a corporeal (perhaps endocrinological) need, a serially articulated demand for bodily replenishment or a weekly affective “fix.” The serialized probing of diegetic bodies is reflexively tied to a complex serialization of the viewer’s own body.

Chronicle of Media Initiative Events

I have added a new rubric (Events) at the top of this page, where I will post future events and maintain a chronicle of past events. While putting this list together, it occurred to me that the media initiative has organized quite a few events over the (nearly) two years of its existence at the Leibniz University Hannover. Here’s a list of things we’ve done:

April 13, 2011: Inaugural meeting of the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research

May 18, 2011: Shane Denson, “Mediatization & Serialization” (public lecture)

June 8, 2011: Media Initiative blog (medieninitiative.wordpress.com) goes online

July 13, 2011: Preliminary meeting of the Film & TV Reading Group

October 26, 2011: First regular meeting of the Film & TV Reading Group (text: Jason Mittell, “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” – moderators: Florian Groß, Shane Denson)

October 27, 2011: “Bollywood Nation” film series begins (organized by Jatin Wagle and Shane Denson, in conjunction with Jatin Wagle’s seminar “Long-Distance Hindu Nationalism and the Changing Figure of the Expatriate Indian in Contemporary Bollywood Cinema”); screening #1: Swades: We, the People (2004)

November 24, 2011: “Bollywood Nation” film series, screening #2: Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995)

November 30, 2011: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Lynn Spigel, “Television, the Housewife, and the Museum of Modern Art” – moderator: Bettina Soller)

December 8, 2011: “Bollywood Nation” film series, screening #3: Pardes (1997)

December 15-17, 2011: “Cultural Distinctions Remediated: Beyond the High, the Low, and the Middle.” International Conference, organized by Ruth Mayer, Vanessa Künnemann, Florian Groß, and Shane Denson. Sponsored by the DFG, DGfA, American Embassy in Berlin, CampusCultur, and in association with the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality—Aesthetics and Practice” and the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research at the Leibniz University of Hannover. Keynote speakers: Jason Mittell and Lynn Spigel. Presentations by Media Initiative members Shane Denson, Florian Groß, Christina Meyer, and Bettina Soller.

December 21, 2011: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Steven Shaviro, “Contagious Allegories: George Romero” – moderator: Stefan Hautke) + film screening: Night of the Living Dead (1968)

January 5, 2012: “Bollywood Nation” film series, screening #4: Mr. and Mrs. Iyer (2002)

January 18, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Livia Monnet, “A-Life and the Uncanny in Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within” – moderator: Thomas Habedank)

January 26, 2012: “Bollywood Nation” film series, screening #5: Chak De! India (2007)

April 25, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Mark B. N. Hansen, “Media Theory” – moderator: Shane Denson)

April 26, 2012: “Chaos Cinema?” film series begins (organized by Felix Brinker, Shane Denson, and Florian Groß); screening #1: “Chaos Cinema” (video essays by Matthias Stork)

May 16, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Steven Shaviro, “Post-Continuity” – moderator: Felix Brinker)

May 24, 2012: “Chaos Cinema?” film series, screening #2: Gladiator (2000); curator: Florian Groß

June 20, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Rudmer Canjels, “Seriality Unbound” – moderator: Ilka Brasch)

June 21, 2012: “Chaos Cinema?” film series, screening #3: Transformers (2007); curator: Shane Denson (presentation: “Discorrelated Images: Chaos Cinema, Post-Cinematic Affect, and Speculative Realism”)

July 2, 2012: Public lecture – Mark B. N. Hansen, “Feed Forward, or the ‘Future’ of 21st Century Media”; First in a week-long series of events with Mark B. N. Hansen (Duke University), co-organized by Shane Denson and Felix Brinker. Grant secured through the Fulbright Senior Specialist Program. Sponsored by the Guest Professor Program of the Faculty of Humanities, American Studies / English Department, and the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research at the Leibniz University of Hannover.

July 3, 2012: Mark B. N. Hansen, “The End of Pharmacology? Historicizing 21st Century Media”; Guest lecture in Shane Denson’s seminar, “Cultural and Media Theory: Media in Transition”

July 5, 2012: “Chaos Cinema?” film series, screening #4: Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010); curator: Felix Brinker (presentation: “Scott Pilgrim Vs. The Movies: Intermedial Collage and Narrative Logic in Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World”)

July 6, 2012: Workshop with Mark B. N. Hansen, including presentations by Media Initiative members Ilka Brasch (“Mapping the Ends of Human Sense Perception”), Felix Brinker (“Between Life and Technics”), and Shane Denson (“Mediate. Discorrelate. Recalibrate.”)

July 11, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Jack G. Shaheen, “Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People” – moderator: Malte Mühle)

July 17, 2012: Presentations by participants in Shane Denson’s “Digital Media and Humanities Research” course: Linda Kötteritzsch, Julia Schmedes, and Mandy Schwarze, “Bonfire of the Televised Profanities” (blog presentation and discussion of the intersection of TV studies and digital media; Urthe Rehmstedt and Maren Sonnenberg, “Digital Humanities” (video essays).

July 19, 2012: “Chaos Cinema?” film series, screening #5: WALL-E (2008); curator: Shane Denson (presentation: “WALL-E vs. Chaos (Cinema)”)

November 8, 2012: “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity” film series begins (organized by Ilka Brasch, Felix Brinker, and Shane Denson); screening #1: Metropolis (1927); curator: Shane Denson (presentation: “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity – An Introduction”)

November 14, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Walter Benjamin, “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit” – moderator: Shane Denson)

November 29, 2012: “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity” film series, screening #2: Man with a Movie Camera (1929); curator: Felix Brinker (presentation: “Movies, Machines, Modernity: On Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera”)

December 5, 2012: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Jean Baudrillard, “The Ecstasy of Communication” – moderator: Julia Schmedes)

December 13, 2012: “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity” film series, screening #3: M – Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder; curator/presenter: Urs Büttner

December 15, 2012: Shane Denson, “Batman and the ‘Parergodic’ Work of Seriality in Interactive Digital Environments”; presentation in conjunction with the American Studies Research Colloquium

January 16, 2013: Film & TV Reading Group (text: Theodor W. Adorno, “Prolog zum Fernsehen” – moderator: Felix Brinker)

January 17, 2013: “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity” film series, screening #4: Modern Times (1936); curator: Ilka Brasch (presentation: “M: Movies, Machines, Media – Modern Times)

January 22, 2013: Campus-Cultur-Prize 2013 awarded to the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research and the Film & TV Reading Group by CampusCultur e.V. and the Faculty of Humanities of the Leibniz University of Hannover

January 25, 2013: Shane Denson, “On the Phenomenology of Reading Comics”; guest lecture in Felix Brinker’s “Introduction to Visual Culture” seminar

The Graphics of Iterability

Cary Wolfe and Timothy Morton on Environmental Humanities

Man with a Movie Camera (1929): Movies, Machines, Modernity

On November 29, 2012, we will be screening Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), the second film in our series “M: Movies, Machines, Modernity.” (See here for a flyer with more details about our film series, and here for a short video introduction that frames it conceptually.)

In his discussion of Man with a Movie Camera, Roger Ebert begins with the following observation:

In 1929, the year it was released, films had an average shot length (ASL) of 11.2 seconds. “Man With a Movie Camera” had an ASL of 2.3 seconds. The ASL of Michael Bay‘s “Armageddon” was — also 2.3 seconds.

If, as I have argued, Michael Bay’s post-cinematic filmmaking captures something of the nonhuman processing of contemporary life by algorithmic means, then Dziga Vertov’s captured something of the machinic materiality of the modern age — a similarly nonhuman view emphasized in the Kinoks movement (from “kino-oki” or kino-eyes) to which Vertov belonged. From the Wikipedia article on “Kinoks”:

The Kinoks rejected “staged” cinema with its stars, plots, props and studio shooting. They insisted that the cinema of the future be the cinema of fact: newsreels recording the real world, “life caught unawares.” Vertov proclaimed the primacy of camera (“Kino-Eye”) over the human eye. The camera lens was a machine that could be perfected infinitely to grasp the world in its entirety and organize visual chaos into a coherent, objective picture.

But perhaps coherence is in the eye (or kino-eye) of the beholder. As Ebert remarks,

There is a temptation to review the film simply by listing what you will see in it. Machinery, crowds, boats, buildings, production line workers, streets, beaches, crowds, hundreds of individual faces, planes, trains, automobiles, and so on.

In many ways, the film resembles what the object-oriented ontologists, following Ian Bogost, call the “Latour litany“: a rhetorical device, consisting in a list of apparently unrelated things, which peppers the writings of Bruno Latour and is employed extensively in OOO to emphasize the plurality of things or objects populating the world and to encourage a break with our normal tendencies to view them anthropocentrically. Bogost recommends the device in his Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing, and perhaps it’s fair to see Vertov’s general project of the Kino-Eye, and its specific expression in Man with a Movie Camera, as precisely an alien-phenomenological undertaking, designed to help us feel “what it’s like to be a thing” in the modern age.

As for the connection with Michael Bay-style “chaos cinema” and the post-cinematic discorrelation of digital images from the human subject, a recent project, the “Global Participatory Remake” of Man with a Movie Camera, brings the two types of alien phenomenologies — the contemporary algorithmic/database-driven and Vertov’s filmic kino-eye — together in an exciting way. At the same time, this project might be seen to raise some rather unsettling questions. What is the relation of contemporary “participatory culture” to the ideals of socialism, when the empowerment experienced by the participants is grounded in the same informatic infrastructure that turns our own entertainment into “immaterial labor” exploitable by corporations wielding algorithms incommensurable with our human concerns, values, perspectives? While the “Global Remake” is hardly guilty, I think, of such exploitation, it enjoins us materially to attend to media-historical and political changes, and to recall that while Vertov’s project was undertaken in the cause of the Revolution, we still have to assess what the revolutionary potential might be — if any, either historical or contemporary — of an alien phenomenology…

As always, the screening (6:00pm on Thursday, Nov. 29, in room 615, Conti-Hochhaus) is free and open to all, so spread the word to anyone who might be interested in joining us. Feel free also to bring along snacks and refreshments. More info here and here.