Everyone knows “the duck-rabbit,” the figure seen above, which Wittgenstein elevated to the lovably cute and velvety philosophical icon of visual multistability. Well, Mr. Duck-Rabbit, meet your evil cousin, “Harmlos wirkender Rattentod” (Seemingly Harmless Rat-Death), as conceived by my son Ari:

Category: Things

Non-correlational media theory?

In chapter 6 of my dissertation, I ask: “what would it mean to think media beyond correlationism?” In the above video, a computer (or code) repeatedly asks another computer (or code): “What would it mean to think media non-correlationally?”

According to the (presumably human-generated) description of the video on YouTube, the famous “Eliza algorithm discusses about object oriented ontology with another code that selects sentences from a corpus of related material. Result is an object oriented (alien) version of Turing test.”

Interestingly, though not surprisingly, Eliza has no answer to the question of what it would mean to think media non-correlationally. She/it responds with other questions: “What comes to mind when you ask that?”, “Why do you ask?”, “Have you asked anyone else?”, or “Does that question interest you?” On the whole, fair questions, I suppose.

[Incidentally, I just googled the question as worded by the computer, i.e. “What would it mean to think media non-correlationally?”, to see what corpus the code is drawing on. Interestingly, it seems that those were in fact my own words, which I posted in a comment on Jussi Parikka’s blog Machinology back in December (his post here: “OOQ — Object-Oriented-Questions”). I’m intrigued now to know who posted the video — who the YouTube user TheTuib is, if in fact it’s a human person…]

Crosseyed and Painless

Above, “Crosseyed and Painless” by the Talking Heads: this is the video which set the stage for Timothy Morton’s energetic and thought-provoking talk at the Nonhuman Turn conference the other day (you can find a video of the complete talk here, and the slides are posted on Morton’s blog here). The music video itself is amazing enough to warrant posting it here separately, though, and I am quite sympathetic to Morton’s rereading of its so-called “postmodernism” in terms of an awareness of the nonhumans that are progressively reshaping our world (in the guises of capital and ecological disaster, for example, but also media changes). Enjoy!

Speculation

[vimeo 39947942 w=500 h=281]

Patrick Jagoda, assistant professor in the English Department at the University of Chicago and co-editor of Critical Inquiry, recently informed me of a project he’s been working on and asked me to spread the word, which I gladly do:

As Patrick puts it, it’s “a transmedia game (or ‘alternate reality game’)” that he’s “co-directing with Katherine Hayles (Duke) and Patrick LeMieux (Duke), and designing with several people at the University of Chicago, Duke, and the University of Waterloo. The game, called Speculation, launched just a few days ago and will continue for several weeks. It has a science fiction narrative and confronts finance culture and the recent economic crisis. The latest trailer is here: vimeo.com/39947942. It leads to the main game site at: http://speculat1on.net/ (complete with a discussion forum, cryptographic puzzles, games of various genres, narrative pieces, audio, and much more). There’s also a related Facebook page that belongs to Nex Noitaluceps.”

I’ve poked around the site a bit, and it’s really quite intriguing, so do check it out!

Of Baboons, Touchscreens, and 4-Letter Words: Or, Nonhuman Agency and an Object-Oriented Perspective on the Pre-Discursive Origins of Language

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dhUPpBOXr8]

As Sharon Begley puts it in her article for Reuters (“This is Dan. Dan is a Baboon. Read, Dan, Read”): “No one is exactly using the words ‘reading’ and ‘baboons’ in the same sentence, but a study published Thursday comes close.”

In a sense, though, the temptation to describe the implications of that study (summarized in the video above) as a demonstration that “baboons can read” is just another iteration of a familiar tendency to anthropomorphize nonhuman primates rather than to draw the converse and much more interesting sorts of conclusions suggested by observing these animals’ behavior: Rather than humanizing apes, I suggest, we should be led by studies like this one to relax our anthropocentric perspectives and to appreciate the nonhuman aspects of those activities and skills, such as language-use, that are typically seen to distinguish us most centrally as human.

While the implications of the experiment shown here are interesting from a wide variety of scientific and philosophical perspectives, they are of especial interest from a media-theoretical perspective, especially one (like mine) that’s interested in pre-, sub-, or non-discursive interactions between bodies and things.

To quote again from Begley’s article:

The study was intended less to probe animal intelligence than to explore how a brain might learn to read. It suggests that, contrary to prevailing theory, a brain can take the first steps toward reading without having language, since baboons don’t.

“Their results suggest that the basic biological mechanisms required for reading have deeper evolutionary roots than anyone thought,” said neuroscientist Michael Platt of Duke University, who co-authored an analysis of the study. “That suggests that reading draws on much older neurological mechanisms” and that apes or monkeys are the place to look for them.

Reading has long puzzled neuroscientists. Once some humans started doing it (about 5,000 years ago in the Middle East), reading spread across the ancient world so quickly that it cannot have required genetic changes and entirely new brain circuitry. Those don’t evolve quickly enough. Instead, its rapid spread suggests that reading co-opted existing neural structures.

Furthermore, as this article at BBC Nature succinctly puts it: “The results suggest the ability to recognise words could more closely relate to object identification than linguistic skill.”

Dr Grainger [one of the scientists responsible for the study] told BBC Nature that recognising letter sequences – previously considered a fundamental “building block” of language – could be related to a more simple skill.

“The baboons use information about letters and the relations between letters in order to perform our task… This is based on a very basic ability to identify everyday objects in the environment,” he said.

Of course, it’s not like this settles things, but it does suggest some interesting correlations between eyes, hands, and objects — embodied, techno-material correlations of a straightforwardly nonhuman sort — that would seem to be basic to the constitution of discursive (human) subjectivities, and not vice versa. Thus, rather than bringing the apes into the citadel of humanity, perhaps we should let them lead us out of the prison-house of language!

More Nonhumans

Kara: Digitally Rendered Frankenstein

Frankenstein films have always been as much about the technological animation of a monster as they are about the medium’s own ability to animate still images. In all of its renderings, Frankenstein also carries traces of the gendered struggles encoded by its first creator, the novel’s author Mary Shelley, who describes the creation of the famous monster — the visual centerpiece of every Frankenstein film — in far less detail than she devotes to the assembly and violent last-minute destruction of its would-be female companion. Films such as James Whale’s classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Terence Fisher’s Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), or Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) consummate this forbidden act of female creation — i.e. the creation of and not by a woman. They oscillate then between their represented storyworlds and a sort of “frenzy of the visible” (as Linda Williams puts it in her classic study of pornography), consisting in these cases of both a filmic objectification of the woman and a foregrounding of the extradiegetic, medial means of her animation.

Quantic Dream (the French game studio most famous for Heavy Rain) follows in this tradition with their recent demo video “Kara,” shown at the Game Developer’s Conference 2012 in San Francisco (March 5-9) and embedded here. The artificial woman’s body is the vehicle by which the technology itself of animation — the realtime rendering of audiovisual content on a PlayStation 3 — can be made the object of attention. The shifting figure/ground relations between diegetic and non-diegetic levels are made concrete in their correlations with the game of peek-a-boo played with the female android’s body: we see right through her, into the deepest recesses of her artificial anatomy, but a hint of clothing prevents any indecent sights once the envelope of her skin is complete.

The — unseen — engineer marvels, “My God!,” as he reflects on the implications of Kara’s unexpected development of sentience, and on the fact that, despite his better judgment, he refrains from dismantling her and allows her to live. Standing proxy for the spectator in front of the screen, the engineer’s exclamation is also centrally about directing our attention towards the visual surface of the screen — both towards the erotic attraction of Kara’s (supposedly) breathtakingly beautiful body, and towards the assemblage of machinery and code that is capable of bringing it to life.

According to Quantic Dream, the program code/video demonstrates the emotional depth that video games are capable of generating. Clearly, though, it is designed above all to demonstrate technological sophistication — and recalling that the spectacle is rendered in real time on a PS3, it is indeed quite impressive. But if emotional maturity and depth were really at stake here, would it be necessary to instrumentalize the female body in this way? Finally, though, we see here a further demonstration of the continued persistence of the Frankensteinian model — with all its problematic intertwinings of biological, technological, sexual, and media-oriented questions and themes — in shaping our fantasies and imaginations, both for better and for worse, with regard to our visions of the (near) future and the possibilities it holds for novel anthropotechnical relations: whether in the field of android-assisted living or in the space of our living rooms, where in the name of “playing games” we have rapidly grown accustomed to interacting with nonhuman agencies.

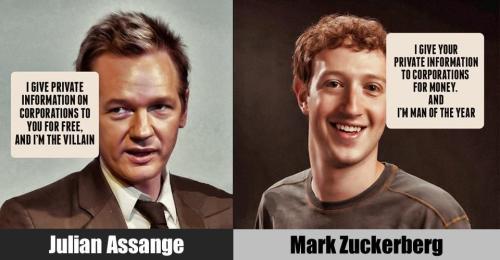

Assange vs. Zuckerberg

(Several versions of the above seem to be circulating right now. I found this one on Graham Harman’s blog.)

Transmediale Impressionen

[brightcove vid=1428803844001&exp3=71239018001&surl=http://c.brightcove.com/services&pubid=18140073001&pk=AQ~~,AAAABDk7jCk~,Hc7JUgOccNrJEfCrmXm47o33h5TBn3UD&lbu=http://www.zeit.de/video/2012-02/1428803844001&w=300&h=225]

Object-Oriented Gaga and the Nonhuman Turn

A while back, I posted the CFP for a conference on “The Nonhuman Turn in 21st Century Studies” to be held at the Center for 21st Century Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, May 3-5, 2012 (the original announcement is here). The lineup of invited speakers, in case you haven’t seen it, is very impressive:

Jane Bennett (Political Science, Johns Hopkins)

Ian Bogost (Literature, Communication, Culture, Georgia Tech)

Wendy Chun (Media and Modern Culture, Brown)

Mark Hansen (Literature, Duke)

Erin Manning (Philosophy/Dance, Concordia University, Montreal)

Brian Massumi (Philosophy, University of Montreal)

Tim Morton (English, UC-Davis)

Steven Shaviro (English, Wayne State)

In addition to these speakers, there will also be several breakout sessions at the conference. And, as luck would have it, I will be presenting in one of them, as the paper I proposed on Lady Gaga and the role of nonhuman agency in twenty-first century celebrity has been accepted by the conference organizers! I am honored and excited to have the chance to speak in such distinguished company, and I very much look forward to the conference. In the meantime, here is the abstract for my talk:

Object-Oriented Gaga: Theorizing the Nonhuman Mediation of Twenty-First Century Celebrity

Shane Denson, Leibniz Universität Hannover

In this paper, I wish to explore (from a primarily media-theoretical perspective) how concepts of nonhuman agency and the distribution of human agency across networks of nonhuman objects contribute to, and help illuminate, an ongoing redefinition of celebrity personae in twenty-first century popular culture. As my central case study, I propose looking at Lady Gaga as a “serial figure”—as a persona that, not unlike figures such as Batman, Frankenstein, Dracula, or Tarzan, is serially instantiated across a variety of media, repeatedly restaged and remixed through an interplay of repetition and variation, thus embodying seriality as a plurimedial interface between trajectories of continuity and discontinuity. As with classic serial figures, whose liminal, double, or secret identities broker traffic between disparate—diegetic and extradiegetic, i.e. medial—times and spaces, so too does Lady Gaga articulate together various media (music, video, fashion, social media) and various sociocultural spheres, values, and identifications (mainstream, alternative, kitsch, pop/art, straight, queer). In this sense, Gaga may be seen to follow in the line of Elvis, David Bowie, and Madonna, among others. Setting these stars in relation to iconic fictional characters shaped by their many transitions between literature, film, radio, television, and digital media promises to shed light on the changing medial contours of contemporary popularity—especially when we consider the formal properties that enable serial figures’ longevity and flexibility: above all, their firm iconic grounding in networks of nonhuman objects (capes, masks, fangs, neckbolts, etc.) and their ontological vacillations between the human and the nonhuman (the animal, the technical, or the monstrous). Serial figures define a nexus of seriality and mediality, and by straddling the divide between medial “inside” and “outside” (e.g. between diegesis and framing medium, fiction and the “real world”), they are able to track media transformations over time and offer up images of the interconnected processes of medial and cultural change. This ability is grounded, then, in the inherent “queerness” of serial figures—the queer duplicity of their diegetic identities, of their extra- and intermedial proliferations, and of the networks of objects that define them. Lady Gaga transforms this queerness from a medial condition into an explicit ideology, one which sits uneasily between the mainstream and the exceptional, and she does so on the basis of a network of queer nonhuman objects—disco sticks, disco gloves, iPod LCD glasses, etc.—that alternate between (anthropocentrically defined) functionality and a sheer ornamentality of the object, in the process destabilizing the agency of the individual star and dispersing it amongst a network of nonhuman agencies. As an object-oriented serial figure, I propose, Lady Gaga may be an image of our contemporary convergence culture itself.