Sight & Sound has just published its annual survey of best video essays, with responses from 47 video essay makers, scholars, curators, and critics. David Verdeure and Irina Trocan led this massive poll, which gathers votes for over 200 titles, many of which I have not yet seen.

I was happy to be included in the survey this year and to recommend a few titles that might not be on people’s radars:

Here’s my list for 2018, which reflects (increasingly as you move down the list) my interest in things that should clearly count as videographic work while problematizing key terms such as video essay, videographic criticism and maybe even video.

Minnelli Red Carlos Valladares (a former student and recent graduate of the Stanford Film & Media Studies Program)

I especially like the attention that is given to the role that red as red, i.e. as a material/medial phenomenon, plays in articulating thematic, atmospheric and ultimately auteurist expressions. The video ran at the Pesaro Film Festival this year.

How Black Lives Matter in The Wire Jason Mittell

While it remains a more or less ‘conventional’ video essay in many respects (voiceover-driven, incorporating close analysis, etc.), I appreciate the way this video pushes at the closure of formal/thematic analyses and asks difficult questions about the relations between fiction and reality – and thus about the role of criticism as mediating between and among them.

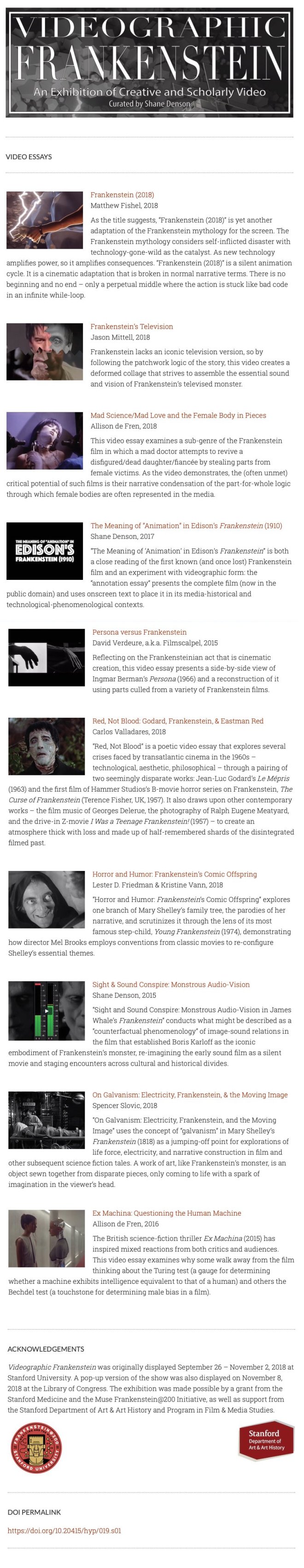

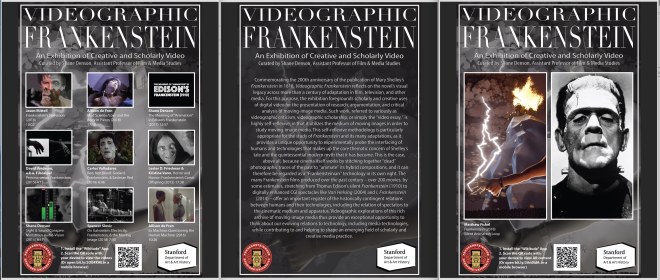

Mad Science/Mad Love and the Female Body in Pieces Allison de Fren

This piece was commissioned for Videographic Frankenstein, an exhibition I curated at Stanford in Fall 2018. It continues Allison’s videographic explorations of gender, media and technology from earlier works (such as her popular Ex Machina: Questioning the Human Machine and Fembot in a Red Dress) with a view to an unexpected and fascinating collection of works ranging from Franju’s Eyes without a Face (1960) to the campy Frankenhooker (1990). The video isn’t online yet, but be on the lookout for an open-access publication of the complete Videographic Frankenstein exhibition coming very soon!

Bottled Songs Chloé Galibert-Lainé and Kevin B. Lee

Though I have only seen fragments of this series of videos, I am confident in saying that this is groundbreaking work that takes Lee’s notion of the ‘desktop documentary’ (as enacted in his Transformers: The Premake) to the next level. The collaborative videos probe the screen as a space of production, while reflecting on the underlying networks, both human and nonhuman, that are operative in online radicalisation and terrorism recruitment.

Touch James J. Hodge, C.A. Davis, and John Bresland

This is another work that breaks with the conventional focus on fictional works and turns instead to the messy spaces of online media cultures, probing the relations of everyday genres like animated GIFs, supercuts and ASMR videos to the pleasures and anxieties we experience in a world of always-on computing.

The Apartment David Verdeure (Filmscalpel)

This is a wonderful example of what has been called, following Jerome McGann and Lisa Samuels, “deformative” criticism. The concept has been expanded by Mark Sample into a “deformative humanities” and adapted for videographic work by people including Kevin Ferguson and Jason Mittell, outlining an exploratory alternative to explanatory essay forms.

One of the things I like best about this piece is the way it evokes what Neil Harris, in his writings on P.T. Barnum, calls an “operational aesthetic” – we (especially if we are people doing videographic work) look at this video and are engaged by the mediated images, which invite us to dwell in them, but we’re also fascinated by Verdeure’s process: how he pulled it off. Many early comments on Facebook revolved precisely around this question of process, which in cases like this do not detract from but indeed add to the layers of audiovisual experience.

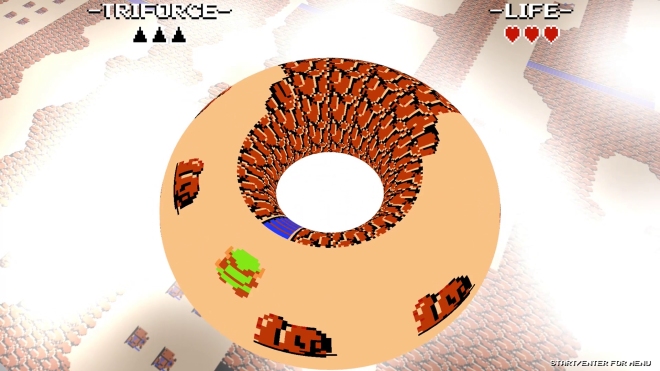

The Topologies of Zelda: Triforce Patrick LeMieux and Stephanie Boluk

This is the farthest from what we typically (at least for now) mean by videographic or audiovisual criticism: it is not a linear video but a playable object – a videogame. And not just any game but a ‘metagame’, a game about games (about The Legend of Zelda in particular, but more generally about topologies and interfaces with videogames as systems and as screen phenomena).

As such, it is clearly a work of criticism, and one that is staged in moving images and sounds – so it should qualify for this list. It even contains scholarly asides and shout-outs to theorists like Vivian Sobchack – probably a first for videogames. More importantly, it can be seen as an important provocation in our ongoing efforts to imagine what scholarly and critical videographic work can be.