Below you’ll find the full text of my talk from the Weird DH panel organized by Mark Sample at the 2016 MLA conference in Austin Texas. Other speakers on the panel included Jeremy Justus, Micki Kaufman, and Kim Knight.

***

Speculative Data: Post-Empirical Approaches to the “Datafication” of Affect and Activity

Shane Denson, Duke University

A common critique of the digital humanities questions the relevance (or propriety) of quantitative, data-based methods for the study of literature and culture; in its most extreme form, this type of criticism insinuates a complicity between DH and the neoliberal techno-culture that turns all human activity, if not all of life itself, into “big data” to be mined for profit. Now, it may sound from this description that I am simply setting up a strawman to knock down, so I should admit up front that I am not wholly unsympathetic to the critique of datafication. But I do want to complicate things a bit. Specifically, I want to draw on recent reconceptions of DH as “deformed humanities” – as an aesthetically and politically invested field of “deformance”-based practice – and describe some ways in which a decidedly “weird” DH can avail itself of data collection in order to interrogate and critique “datafication” itself.

My focus is on work conducted in and around Duke University’s S-1: Speculative Sensation Lab, where literary scholars, media theorists, artists, and “makers” of all sorts collaborate on projects that blur the boundaries between art and digital scholarship. The S-1 Lab, co-directed by Mark Hansen and Mark Olson, experiments with biometric and environmental sensing technologies to expand our access to sensory experience beyond the five senses. Much of our work involves making “things to think with,” i.e. experimental “set-ups” designed to generate theoretical and aesthetic insight and to focus our mediated sensory apparatus on the conditions of mediation itself. Harnessing digital technologies for the work of media theory, this experimentation can rightly be classed, alongside such practices as “critical making,” in the broad space of the digital humanities. But due to their emphatically self-reflexive nature, these experiments challenge borders between theory and practice, scholarship and art, and must therefore be qualified, following Mark Sample, as decidedly “weird DH.”

One such project, Manifest Data, uses a piece of “benevolent spyware” that collects and parses data about personal Internet usage in such a way as to produce 3D-printable sculptural objects, thus giving form to data and reclaiming its personal value from corporate cooptation. In a way that is both symbolic and material, this project counters the invisibility and “naturalness” of mechanisms by which companies like Google and Facebook expropriate value from the data we produce. Through a series of translations between the digital and the physical—through a multi-stage process of collecting, sculpting, resculpting, and manifesting data in virtual, physical, and augmented spaces—the project highlights the materiality of the interface between human and nonhuman agencies in an increasingly datafied field of activity. (If you’re interested in this project, which involves “data portraits” based on users’ online activity and even some weird data-driven garden gnomes designed to dispel the bad spirits of digital capital, you can read more about it in the latest issue of Hyperrhiz.)

Another ongoing project, about which I will say more in a moment, uses data collected through (scientifically questionable) biofeedback devices to perform realtime collective transformations of audiovisual materials, opening theoretical notions of what Steven Shaviro calls “post-cinematic affect” to robustly material, media-archaeological, and aesthetic investigations.

These and other projects, I contend, point the way towards a truly “weird DH” that is reflexive enough to suspect its own data-driven methods but not paralyzed into inactivity.

Weird DH and/as Digital Critical (Media) Studies:

So I’m trying to position these projects as a form of weird digital critical (media) studies, designed to enact and reflect (in increasingly self-reflexive ways) on the use of digital tools and processes for the interrogation of the material, cultural, and medial parameters of life in digital environments.

Using digital techniques to reflect on the affordances and limitations of digital media and interfaces, these projects are close in spirit to new media art, but they are also apposite with practices and theories of “digital rhetoric,” as described by Doug Eyman, with Gregory Ulman’s “electracy,” or with Casey Boyle’s posthuman rhetoric of multistability, which celebrates the rhetorical affordances of digital glitches in exposing the affordances and limitations of computational media in the broader realm of an interagential relational field that includes both humans and nonhumans. In short, these projects enact what we might call, following Stanley Cavell, the “automatisms” of digital media – the generative affordances and limitations that are constantly produced, reproduced, and potentially transformed or “deformed” in creative engagements with media. Digital tools are used in such a way as to problematize their very instrumentality, hence moving towards a post-empirical or post-positivistic form of datafication as much as towards a post-instrumental digitality.

Algorithmic Nickelodeon / Datafied Attention:

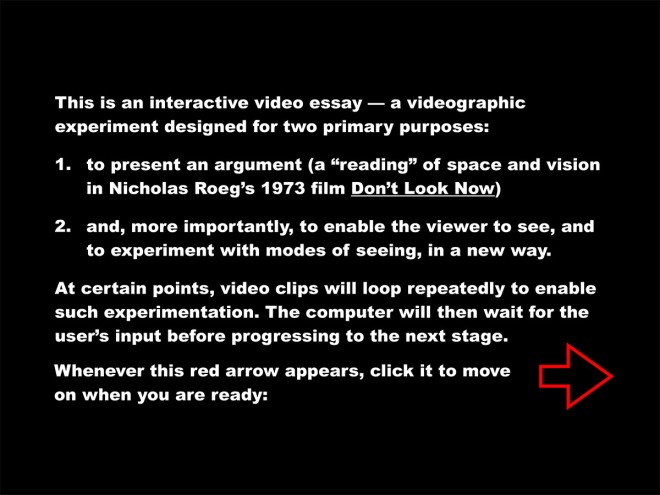

My key example is a project tentatively called the “algorithmic nickelodeon.” Here we use consumer-grade EEG headsets to interrogate the media-technical construction and capture of human attention, and thus to complicate datafication by subjecting it to self-reflexive, speculative, and media-archaeological operations. The devices in question cost about $100 and are marketed as tools for improving concentration, attention, and memory. The headset measures a variety of brainwave activity and, by means of a proprietary algorithm, computes values for “attention” and “meditation” that can be tracked and, with the help of software applications, trained and supposedly optimized. In the S-1 Lab, we have sought to tap into these processes in order not just to criticize the scientifically dubious nature of these claims but rather to probe and better understand the nature of the automatisms and interfaces taking place here and in media of attention more generally. Specifically, we have designed a film- and media-theoretical application of the apparatus, which allows us to think early and contemporary moving images together, to conceive pre- and post-cinema in terms of their common deviations from the attention economy of classical cinema, and to reflect more broadly on the technological-material reorganizations of attention involved in media change. This is an emphatically experimental (that is, speculative, post-positivistic) application, and it involves a sort of post-cinematic reenactment of early film’s viewing situations in the context of traveling shows, vaudeville theaters, and nickelodeons. With the help of a Python script written by lab member Luke Caldwell, a group of viewers wearing the Neurosky EEG devices influence the playback of video clips in real time, for example changing the speed of a video or the size of the projected image in response to changes in attention as registered through brain-wave activity.

At the center of the experimentation is the fact of “time-axis manipulation,” which Friedrich Kittler highlights as one of the truly novel affordances of technical media, like the phonograph and cinema, that arose around 1900 and marked, for him, a radical departure from the symbolic realms of pre-technical arts and literature. Now it became possible to inscribe “reality itself,” or to record a spectrum of frequencies (like sound and light) directly, unfiltered through alphabetic writing; and it became possible as well to manipulate the speed or even playback direction of this reality.

Recall that the cinema’s standard of 24 fps only solidified and became obligatory with the introduction of sound, as a solution to a concrete problem introduced by the addition of a sonic register to filmic images. Before the late 1920s, and especially in the first two decades of film, there was a great deal of variability in projection speed, and this was “a feature, not a bug” of the early cinematic setup. Kittler writes: “standardization is always upper management’s escape from technological possibilities. In serious matters such as test procedures or mass entertainment, TAM [time-axis manipulation] remains triumphant. [….] frequency modulation is indeed the technological correlative of attention” (Gramophone Film Typewriter 34-35). Kittler’s pomp aside, his statement highlights a significant fact about the early film experience: Early projectionists, who were simultaneously film editors and entertainers in their own right, would modulate the speed of their hand-cranked apparatuses in response to their audience’s interest and attention. If the audience was bored by a plodding bit of exposition, the projectionist could speed it up to get to a more exciting part of the movie, for example. Crucially, though: the early projectionist could only respond to the outward signs of the audience’s interest, excitement, or attention – as embodied, for example, in a yawn, a boo, or a cheer.

But with the help of an EEG, we can read human attention – or some construction of “attention” – directly, even in cases where there is no outward or voluntary expression of it, and even without its conscious registration. By correlating the speed of projection to these inward and involuntary movements of the audience’s neurological apparatus, such that low attention levels cause the images to speed up or slow down, attention is rendered visible and, to a certain extent, opened to conscious and collective efforts to manipulate it and the frequency of images now indexed to it.

According to Hugo Münsterberg, who wrote one of the first book-length works of film theory in 1916, cinema’s images anyway embody, externalize, and make visible the faculties of human psychology; “attention,” for example, is said to be embodied by the close-up. With our EEG setup, we can literalize Münsterberg’s claim by correlating higher attention levels with a greater zoom factor applied to the projected image. If the audience pays attention, the image grows; if attention flags, the image shrinks. But this literalization raises more questions than it answers, it would seem. On the one hand, it participates in a process of “datafication,” turning brain wave patterns into a stream of data called “attention,” but whose relation to attention in ordinary senses is altogether unclear. But this datafication simultaneously opens up a space of affective or aesthetic experience in which the problematic nature of the experimental “set-up” announces itself to us in a self-reflexive doubling: we realize suddenly that “it’s a setup”; “we’ve been framed” – first by the cinema’s construction of attentive spectators and now by this digital apparatus that treats attention as an algorithmically computed value.

So in a way, the apparatus is a pedagogical/didactic tool: it not only allows us to reenact (in a highly transformed manner) the experience of early cinema, but it also helps us to think about the construction of “attention” itself in technical apparatuses both then and now. In addition to this function, it also generates a lot of data that can indeed be subjected to statistical analysis, correlation, and visualization, and that might be marshaled in arguments about the comparative medial impacts or effects of various media regimes. Our point, however, remains more critical, and highly dubious of any positivistic understanding of this data. The technocrats of the advertising industry, the true inheritors of Münsterberg the industrial psychologist, are anyway much more effective at instrumentalizing attention and reducing it to a psychotechnical variable. With a sufficiently “weird” DH approach, we hope to stimulate a more speculative, non-positivistic, and hence post-empirical relation to such datafication. Remitting contemporary attention procedures to the early establishment of what Kittler refers to as the “link between physiology and technology” (73) upon which modern entertainment media are built, this weird DH aims not only to explore the current transformations of affect, attention, and agency – that is, to study their reconfigurations – but also potentially to empower media users to influence such configuration, if only on a small scale, rather than leave it completely up to the technocrats.