Daniel Stein, my indefatigable friend, colleague, and co-editor of Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives (forthcoming from Continuum next year), has just published his monograph Music Is My Life: Louis Armstrong, Autobiography, and American Jazz with the University of Michigan Press. The book is the first extended study of the relation between Louis Armstrong’s writing practices and musical performances and offers a cultural theory of

intermedia and transmedia autobiographics.

On this occasion, Daniel has written a guest blog post on “Armstrong, autobiographics, and a Disney alligator” at the University of Michigan Press blog, which I have been authorized to reproduce here:

The millions of people who went to the movie theaters to watch Disney’s animated film The Princess and the Frog (dir. Ron Clemens and John Musker, 2009) encountered a singing and trumpeting alligator named Louis. Set in a mythologized New Orleans of the 1920s, the movie cooks up a gumbo of popular ingredients ranging from the city’s famous street parades and Mississippi entertainment ships to highly stylized images of Harlem Renaissance dance hall decors. While the anthropomorphic Louis is only one of many side characters, he is especially noteworthy because he pays homage to one of New Orleans’s most famous sons and one of America’s most popular twentieth-century icons: the jazz trumpeter, singer, and actor Louis Armstrong (1901-1971).

For many of Disney’s viewers, connecting the lovable cartoon alligator with the historical Louis Armstrong would have been relatively easy (the trumpet style and speaking voice pretty much give it away). Indeed, ever since Ken Burns’s highly acclaimed PBS documentaryJazz (2001), Armstrong has perhaps been the most visible and readily identifiable figure in American culture. But as I argue in my book, it was not just audiences, journalists, biographers, and documentary filmmakers who contributed to Armstrong’s lasting status as a jazz legend: Armstrong himself actively impacted his public reception and still shapes our understanding of jazz today. How did that happen? Obviously, his recordings from the 1920s (with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band as well as his own Hot Five and Hot Seven) until the very end of his life (with the All Stars), his relentless touring all over the world, and his many film roles and television appearances add up to a vast sonic and visual archive of material that fans and scholars continue to mine for meaning.

Yet Armstrong was also a writer, and a prolific one at that. He enjoyed only minimal formal education and did not receive any specific literary training, but he began to write on a daily basis when he moved from New Orleans to Chicago in 1922 and did not stop until he passed away almost fifty years later. He did most of his writing on a portable typewriter but wrote in longhand whenever he did not have access to this typewriter. Over the course of his life, he penned thousands of letters and wrote dozens of longer narratives, including two autobiographical books, Swing That Music (partially ghostwritten and published in 1936) and Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans (1954), and a variety of magazine articles, several of which are collected in Thomas Brothers’s Louis Armstrong, in His Own Words: Selected Writings (1999). The Louis Armstrong House Museum in Queens houses many of these and other materials, and I was privileged to draw on some of their holdings for my research.

My book is the first scholarly attempt to conduct a comprehensive study of Armstrong as a writer. As such, it traces his evolution as a writer over several decades and pays particular attention to his idiosyncratic autobiographical practice: his tendency to treat all written expression as a spontaneous form of life writing in which the moment of autobiographical performance is determined by the writer’s interaction with his medium – typewriter, pen, paper – and his imagined audiences. Once we understand Armstrong along these lines as a vernacular storyteller whose objective was to communicate his views about his life and his music, we get a better sense of how central the autobiographical mode was to all of his expressive efforts, including his singing, trumpet playing, and film acting, as well as his curious habit of assembling photo-collages and preserving snapshots of his public and private lives on his tape recorders.

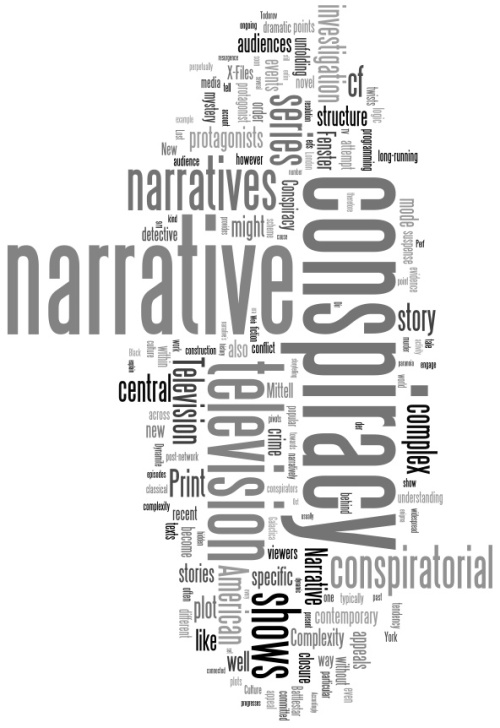

In the first half of the book, I argue that Armstrong was actually an intermedia performer whose central mode of communication was autobiography and whose autobiographical performances across media were characterized by many of the principles that also structure jazz: spontaneity, interaction, variation, and humor. Dissatisfied with formalistic approaches to Armstrong’s jazz and with biographical studies that too often take the musician’s words and actions at face value, the second half of the book offers extensive historical and cultural contextualization of what I call Satchmo’s autobiographics: the cultural resonances evoked in and through Armstrong’s performances across media. It is especially the controversial history of blackface minstrelsy and its modern reformulations by twentieth-century jazz performers that infuse Armstrong’s productive ambiguities: the manifold, and often contradictory, cultural contexts and racial discourses that were produced by his performances and that trouble all too easy declarations of Armstrong as either a submissive “Uncle Tom” (as many of his detractors had it during the civil rights movement) or an exceptionally cunning trickster figure who transcended racial boundaries and stereotypes (as many of his present-day followers would have it).

Crucially, these ambiguities continue to be productive almost four decades after Armstrong’s death. They can be seen and heard in Disney’s Princess and the Frog as well. After all, alligator Louis is both a masterful jazz musician of the highest order and a clumsy, bumbling comical character whom students of American racial stereotypes will readily associate with the actual and figurative blackface representations that have “colored” American popular culture for at least two centuries. Whether Armstrong would have been the jazz figure of choice for this Disney movie had he not written so prolifically about his life and his music must, of course, remain a matter of speculation. But that Armstrong’s LP Disney Songs the Satchmo Way(1968) has caused both vitriolic criticism as an alleged pandering to minstrel conventions and glorious praise for its supposedly sublime interpretations of popular songs is indeed instructive. I think that rather than siding with one of these assessments, we should dig even deeper into the musician’s textual, sonic, and visual archive and continue to trace the ambiguities that make Satchmo’s autobiographics so endlessly fascinating.