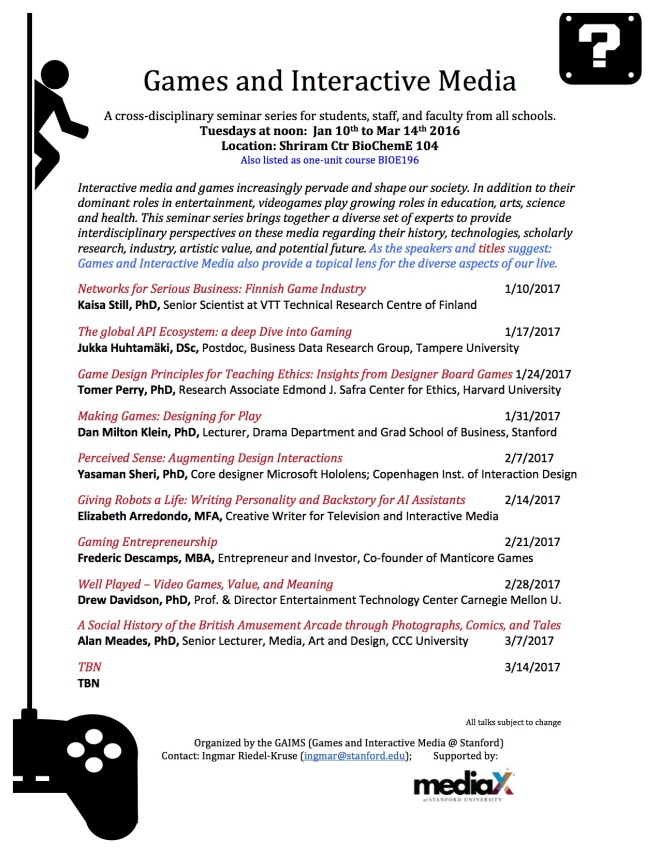

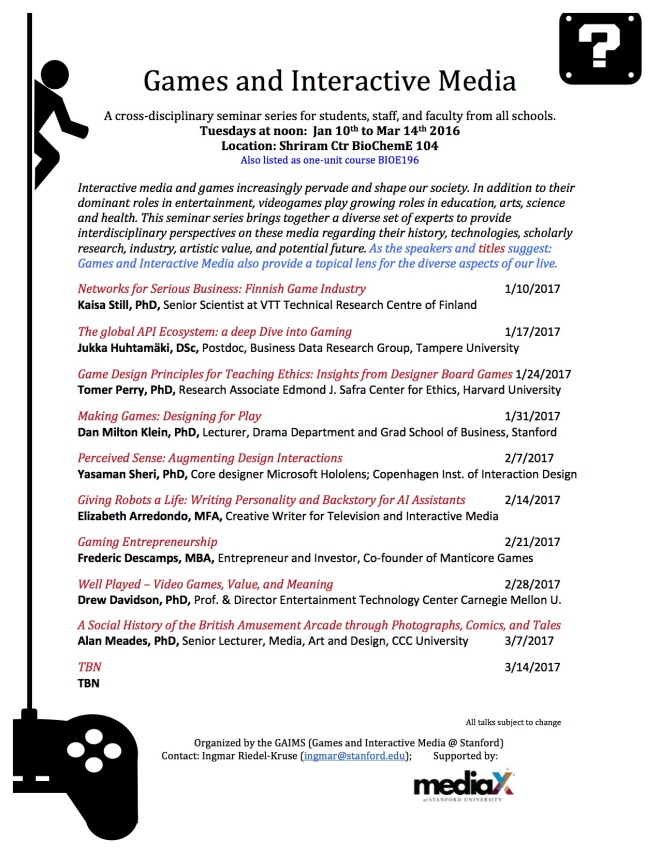

The Games and Interactive Media Series (GAIMS) at Stanford University meets every Tuesday at noon. Above, the list of speakers for Winter Quarter 2017.

The Games and Interactive Media Series (GAIMS) at Stanford University meets every Tuesday at noon. Above, the list of speakers for Winter Quarter 2017.

Above you’ll find the video of my talk, “Digital Seriality: Code & Community in the Super Mario Modding Scene,” which I delivered on September 27, 2016 as part of the Interactive Media & Games Seminar Series at Stanford University.

Here is the abstract for my talk:

Digital Seriality: Code & Community in the Super Mario Modding Scene

Shane Denson

Seriality is a common feature of game franchises, with their various sequels, spin-offs, and other forms of continuation; such serialization informs social processes of community-building among fans, while it also takes place at much lower levels in the repetition and variation that characterizes a series of game levels, for example, or in the modularized and recycled code of game engines. This presentation considers how tools and methods of digital humanities — including “distant reading” and visualization techniques — can shed light on serialization processes in digital games and gaming communities. The vibrant “modding” scene that has arisen around the classic Nintendo game Super Mario Bros. (1985) serves as a case study. Automated “reading” techniques allow us to survey a large collection of fan-based game modifications, while visualization software helps to bridge the gap between code and community, revealing otherwise invisible connections and patterns of seriality.

Here is the full text of my talk from the 2015 conference of the Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts — part of the panel on Video Games’ Extra-Ludic Echoes (organized by David Rambo, and featuring talks by Patrick LeMieux and Stephanie Boluk, David Rambo, and myself).

On the “Parergodic” Work of Seriality in Interactive Digital Environments

Shane Denson (SLSA 2015, Houston, Nov. 15, 2015)

I want to suggest that popular serialized figures function as indexes of historical and media-technical changes, helping us to assess the material and cultural transformations that such figures chart in the process of their serial unfoldings. This function becomes especially pronounced when serial figures move between and among various media. By shifting from a medial “inside” to an “outside” or an in-between, serial figures come to function as higher-order media, turning first-order apparatic media like film and television inside out and exposing them as reversible frames. But with the rise of interactive, networked, and convergent digital media environments, this outside space is called into question, and the medial logic of serial figures is transformed in significant ways. This transformation, I suggest, is not unrelated to the blurring of relations between work and play, between paid labor and the incidental work culled from our entertainment practices. In the age of transmedia, serial figures move flexibly between media much like we move between projects and contexts of consumption and production. The dynamics of border-crossing that characterized earlier serial figures have now been re-functionalized in accordance with the ergodic work of navigating computational networks—in accordance, that is, with work and network forms that frame all aspects of contemporary life.

I will come back to this argument in a moment and elaborate with reference to Batman and his movement from comics to film and video games, but first let me say a few words about “the work of seriality.” In the nineteenth century, production work became increasingly serialized as it was fragmented and mechanized in factories, culminating in the assembly line, the paradigmatic site of serialized production, and eventually leading to digital automation and process control. Ultimately, of course, this trajectory was spearheaded by capitalism’s own seriality, or its structuration as an endless series of M-C-M’ progressions. At the same time, works of culture also fell under the spell of the series. The industrial steam press churned out penny dreadfuls and dime novels, before comic strips, film serials, radio and TV series took over. The simultaneous rise of serialized work practices and serial “works” of culture is too massive, I suggest, to be a sheer coincidence. And concomitant with these two was a third form of serialization: that of cultural identity or of subjective experience itself. As Benedict Anderson and Jean-Paul Sartre before him have argued, new forms of community, identity, and perception were based in the serial work of media, such that, for example, the serialization of daily papers, consumed more or less simultaneously by an entire nation, could produce the nation itself as an “imagined community” of serialized subjects. Anderson’s conception of the serialities of nationhood or the proletariat suggests a material connection between the minute level of concrete serial media practices and the broad level of discursive, cultural, or imagined realities—a connection that I want to pursue into the realm of digital media.

I want to suggest that serialized media are able to leverage these shifts in the nature of work/works because they function according to the logic of the “parergon,” as described by Jacques Derrida. Etymologically, the term parergon is composed of the prefix “para-” (next to, or beside) and “ergon,” which derives from Greek for work. The parergon is thus literally “next to the work,” marginal or supplementary to it, as a frame is with respect to a painting (or an hors d’oeuvre with respect to the main course of a meal).

But the picture frame in particular demonstrates an essential reversibility: on the one hand, the frame serves as a background for the work, as a ground for the image it frames and selects or presents. On the other hand, the frame can also be absorbed into the figure when seen against the larger background of the wall, as when we take a broad view of a row of paintings on a museum wall before selecting one to observe more closely. The frame is therefore subject to repeated figure/ground reversals, and it’s the same with serialized media, which are constituted in the flickering interplay between an ongoing sequence and its articulation into discrete segments.

A serial figure like Frankenstein’s monster embodies this interplay and mediates it as a higher-order reflection on media change. The monster is of course part of a film’s diegetic universe, for example, but it also exceeds that frame and partakes in a plurimedial series of instantiations. We never just see Frankenstein’s monster; we see an iteration of the monster that stands in extradiegetic relation to Karloff’s iconic portrayal and to a series of media and mediations of the figure. And we should not forget that Karloff’s mute monster, which contrasts sharply with the eloquent monster of Shelley’s novel, once served to foreground the transition from silent cinema to the talkies. Figure/ground reversibility is an essential precondition for plurimedial seriality as such, specifically enabling the foregrounding of mediality that allows the serial figure to serve as a figuration of media change.

But with the rise of digital media, the formerly discrete media across which serial figures were deployed come to mingle in much closer proximity. What Henry Jenkins calls our “convergence culture” responds by coming up with new ways to tell stories (and to sell commodities) that take advantage of the coming-together of media in the space of the digital. In Jenkins’s version, transmedia storytelling is inherently serial, but much less linear than a conventional television series might be, as it allows the reader/viewer/player/user to explore various facets of a story-world through movies, games, textual and other forms, allowing for a variable order of consumption that corresponds, we might say, to the database structures in which digital information is stored and (interactively) accessed. But transmedia storytelling often aims to smooth over the disjunctures between media installments; the parergonal logic of figure/ground reversals that sustained serial figures and allowed them to track and foreground media changes is thus transformed. A serial figure like Batman thrives in this new environment and traces this transformation in relation to computational mediation and the shift from a parergonal to what I call a parergodic logic.

With the term parergodics, I want to link Derrida’s notion of the parergon with Espen Aarseth’s use of the term ergodics to describe processes and structures of digital interactivity. Ergodics combines the Greek ergon (work) and hodos (path), thus positing nontrivial labor as the aesthetic mode of players’ engagement with games. For Aarseth, the arduous or laborious path of ergodic interactivity marks a fundamental difference between digital media such as video games or electronic literature on the one hand and traditional literature and narrative media on the other. For whereas the path of a narrative is fixed for the reader of a novel or the spectator of a film, it must be generated in digital media through a cooperative effort between the user and the computational system. The signs composing the text of a video game—including textual strings, visual perspectives, narrative and audiovisual events—are not (completely) predetermined but generated on the fly, in real time, as the player makes his or her way through the game. Ergodics, the path of the work or the work of the path, therefore describes the nontrivial labor at the heart of gameplay. But to expand this beyond Aarseth’s narrower frame of reference, the concept of ergodics can also be seen to ground a wider variety of interactive and participatory potentials in contemporary culture, where computational networks are implicated virtually ubiquitously in entertainment, social life, and work. The borders between these realms are remarkably unclear (think of all the things people do on social networks and the virtual impossibility of distinguishing clearly between work activities and play), and it would seem that this has something to do with the indifference of computational media to the type of contents processed. This computational indifference to the phenomenological modalities of human experience – or to the differences between the analogue media that at least partly corresponded to those modalities – leads, as Mark Hansen argues, to a divergence between mediation in its classical, perceptually oriented form and a new form of mediation that channels human affect into the process-oriented project of establishing ever greater networks of pure connectivity. This is the larger significance, I propose, of what Steven Shaviro calls “post-cinematic affect”: in contrast to the cinema, which was constituted by the storage and reproduction of perceptual objects, ergodic mediation involves acts of affective interfacing with the fundamentally post-perceptual realm of computation, which is algorithmic, distributed, and nonlocal, in contrast to the phenomenological basis of human embodiment. Clicking on a Youtube video not only delivers perceptual content to your embodied eyes and ears, it also delivers computational content – information about affective, epistemic, and monetary valuations – to the routines of network-constitutive algorithms. In this environment, play activities not only involve the execution of nontrivial work, as Aarseth argues, but corporations and financial interests, among others, continually find clever ways to disguise work as play, to “gamify” our labor, both paid and unpaid, while mining the data generated in the process in order to profit from both dedicated and incidental work. In this environment, as Matteo Pasquinelli has argued, virtually any investment of attention or affect will also generate a surplus value for Google, Facebook, etc. – a value produced and accumulated parasitically, without regard for any significance we may attach to the contents of our digital interactions, by means of computational algorithms functioning on an altogether different level than the human concerns that feed them.

As a result, media “contents” become incidental or marginal to work, so that our so-called “participatory culture” might better be termed a “parergodic culture,” where cultural “contents” are reversibly supplemental to the nontrivial labor of interactive work. But the notion of “parergodic culture” suggests also that there might be para-ergodic margins from which to witness the shift, to take stock of it in the process of its occurrence. This is where the parergon meets ergodics, and it’s in this reversible margin of parergodicity, neither completely inside nor outside the realm of ergodics, that I’d like to situate the serial work of Batman from about the mid 1980s to the present.

The starting point is the appearance of graphic novels such as The Dark Knight Returns (Frank Miller, 1986), Arkham Asylum: Serious House on Serious Earth (Grant Morrison, 1989), and The Killing Joke (Alan Moore, 1988), which re-envisioned Batman as a darker figure and laid the groundwork for the figure’s medial self-awareness.

In their wake, a key scene in Tim Burton’s 1989 film stages a parergonal reversal of medial spaces during Joker’s televised address to Batman and the people of Gotham. The medium takes on an unexpected materiality as the Joker shoves the mayor’s image off the screen, and a crucial reversal is visualized as a shot of several contiguous studio monitors gives way to the various screens united in Batman’s multimedia console. It is here, with a sudden freeze frame interaction, that Batman enacts a further parergonal reversal: while the film’s editing leads us to believe that Bruce Wayne, like all the citizens of Gotham, is viewing the Joker’s address live, he pauses the recording, in effect pausing the continuity of the film itself. And with this seemingly insignificant difference it introduces between live and recorded images, Batman’s pausing of the image announces, in effect, an entry into the interactive space of post-cinematic media. This is the first step towards the reconceptualization of images and visual media as purely processual, computational, and no longer tied to perception as its objects.

Jump ahead twenty years. Computational technologies are implemented more broadly in the actual production of visual media, for example in post-cinematic blockbusters like Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy. Nolan’s second film, The Dark Knight, can be seen as a serial continuation not only of Batman Begins, the first film in Nolan’s trilogy, but also an updating of Burton’s early exploration of Batman’s ergodic mediality.

Most centrally, Nolan’s film updates Batman’s console and places it in the middle of the caped crusader’s pursuits to restore order to Gotham. The film spends a considerable amount of time foregrounding this computational wonder machine, which alternates reversibly with the film itself and serves to foreground its CGI-based spectacles.

Within the frame of the narrative, a new range of computational powers is demonstrated, including biometric facial recognition and computational forensics. Early in the film, Bruce Wayne’s tech guy Lucius Fox demonstrates to him a new technology, utilizing a cell phone to emit an inaudibly high frequency capable of mapping a remote location by means of digitally enhanced sonar. This sets the stage for the film’s climax, when the sonar program is spread, virus-like, to the cell phones of all of Gotham’s inhabitants. Through this network, which feeds into Bruce Wayne’s central console, now equipped with a giant wall of display devices, Batman is able to “see” the whole city.

This is a disembodied or nonlocalized 3D computer-graphics vision generated through a distributed, nonhuman sensory form that substitutes computational process for perceptual object. Seeing through the eyes of a machinic network, Batman is able to find the bad guys just in time for the final showdown, but at a decisive moment Batman’s “vision” machine crashes.

The event is presented to us in first-person perspective, crucially drawing attention to the mediation of our own vision through computational processes. Here the parergonal reversibility between diegetic and medial levels is thoroughly parergodic, as we are made witness to an event that challenges the perceptual frames delineating the narrative and our ability to engage or disengage with the medium.

But the scene anticipates an even more intense experience of parergodic involvement in the video game Arkham Asylum. Here, a specifically parergonal exploration of spatialized boundaries between sanity and insanity that goes back to the graphic novel of the same title is translated into a narrative that weaves back and forth between “reality” and Scarecrow-induced hallucinations. The player, who has to act in order to stay alive, can never be sure when one of these hallucinatory states has begun, and he or she therefore gets drawn into such illusions until an abrupt awakening takes place in the wake of a victory (in a boss battle) or its deferral. Even more poignantly, though, there is a total break with all narrative, perceptual, and actional involvement at one point late in the game, when the images on the screen freeze and display digital artifacts and the soundtrack begins to skip like a scratched CD.

Suddenly, the screen goes black and the game literally reboots – at least, I could swear that my PlayStation restarted at this moment, while a feeling of panic gripped me. When the game restarts, we see images reminiscent of the game’s opening scenes – thus compounding a sense of fear that either my disk or my machine is broken, and that all my progress in the game, by this time some 10 or 20 hours, is lost and will have to be repeated from the beginning. But this time things are backwards: the Joker’s in the driver’s seat, escorting Batman into Arkham Asylum. The cutscene gives way to an interactive sequence where the player controls the Joker, thus instituting a weird sort of actional identification with the villain, who then turns and points a gun directly at the player, whose vision is suddenly realigned with the perspective of Batman. There’s no chance to avoid death, and we see this “Mission failed” screen with the tip, “Use the middle stick to avoid Joker’s gun fire.” Only, there is no middle stick on the PlayStation or Xbox controller. This whole sequence therefore emphasizes the point of interface as a reversible margin where computational or ergodic media converge as both the thematic/actional “content” and the material platform for play.

And the quasi-glitch and simulated crash of the game channel this attention to reveal the significant work involved in ergodic play—the very real panic and extradiegetic fears activated here highlight the cognitive and physical labor invested by the player, the precariousness of the digital platform for the storage or accumulation of such work, over which we have little individual control, though our activities are sure to generate profit for the corporations holding ownership of intellectual properties (like Batman), of proprietary software and hardware (like the console we’re operating), or the algorithms that will mine our activities for surplus value. This, I suggest, is parergodic culture.

David Rambo’s abstract for the panel “Video Games’ Extra-Ludic Echoes” at SLSA 2015 in Houston:

“Spinoza on Completion and Authorial Forces in Video Games”

David Rambo, Duke University

This talk extends the Spinozist paradigm for theorizing the medium-specificity of narrative and agency in video games I presented at SLSA 2013. Whereas Spinoza’s first and second orders of knowledge—phenomenal experience and rational systemization—map easily enough onto a single-player video game as a deterministic Natura; knowledge of the third kind would problematically seem to require an idealistic reduction of the video game into an operational and meaning-making Idea in abstraction from culture, political economy, and perhaps even the body of the player. Looking primarily to the changes made to Blizzard’s multiple releases of Diablo 3 (2012-2014), I propose that completion distinguishes the video game from other cultural forms and allows us to conceive of its essence. Pursuit of a game’s completion echoes, in Frédéric Lordon’s Spinozist terms, the ascription of one’s conatus to an enterprise’s regime of affects. For the notion of a game’s completion appears under the purview of the developers’ and industry’s ulterior motives. On one hand, the player’s motivation to complete a game redounds to the complex of desires that operate part and parcel with a game’s mechanics, marketing, and historical situation. On the other hand, total completion is a barrier that development studios intend to break by marketing supplemental material, exploiting customer data and feedback, issuing patches, and releasing expansion packs. Spinoza’s ontology of affection allows for a rational ordering of this tension between completion and incompletion in the individual playing and mass market consumption of video games.

On April 23-24, 2015, I will be participating in the conference “Thinking Serially: Repetition, Continuation, Adaptation,” hosted by the Department of Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center, CUNY. You can find the full program here, and here is the abstract for the talk I’ll be giving:

Ludic Serialities: Levels of Serialization in Digital Games and Gaming Communities

Shane Denson (Duke University, Program in Literature)

In this paper, I outline several layers of seriality that are operative in and around the medium of digital games. Some of these resemble pre-digital forms of popular seriality, as they have been articulated in commercial entertainments since the nineteenth century; others would seem to be unique to digital formats and the ludic forms of interactivity they facilitate. Thus, the “inter-ludic” seriality of sequels, remakes, and spinoffs that constitute popular game franchises are recognizable in terms of the (predominantly narrative) seriality that has characterized serialized novels, films serials, television series, cinematic remakes and blockbuster trilogies. But these franchises also give rise to “para-ludic” forms of seriality that are more squarely at home in the digital age: games form parts of larger transmedia franchises, which depend in many ways on the infrastructure of the Internet to support exchanges among fans. On the other hand, games also articulate low-level “intra-ludic” serialities through the patterns of repetition and variation that characterize game “levels” and game engines. These serialized patterns are often non-narrative in nature, manifesting themselves in the embodied rhythms instantiated as players interface with games; they therefore challenge the traction of pre-digital conceptions and point to what would appear an unprecedented form of “infra-ludic” serialization at the level of code and hardware. Interestingly, however, such ultra-low-level serialities remain imbricated with the high-level seriality of socio-cultural exchange; levels of code and community cross, for example, in highly serialized modding communities.

This presentation takes a comparative approach in order to identify historical, cultural, and medial specificities and overlaps between digital and pre-digital forms of seriality. Besides outlining the levels of seriality described above, I will also look at methodological challenges for studying these new forms, as well as several approaches (including both close and “distant” forms of reading) designed to meet these challenges.

Bibliography:

Boluk, Stephanie, and Patrick LeMieux. “Hundred Thousand Billion Fingers: Seriality and Critical Game Practices.” Leonardo Electronic Almanac 17.2 (2012): 10-31. http://www.leoalmanac.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/LEAVol17No2- BolukLemieux.pdf

Denson, Shane, and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann. “Digital Seriality: On the Serial Aesthetics and Practice of Digital Games.” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 7.1 (2013): 1-32. http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/vol7no1-1/7-1-1- pdf

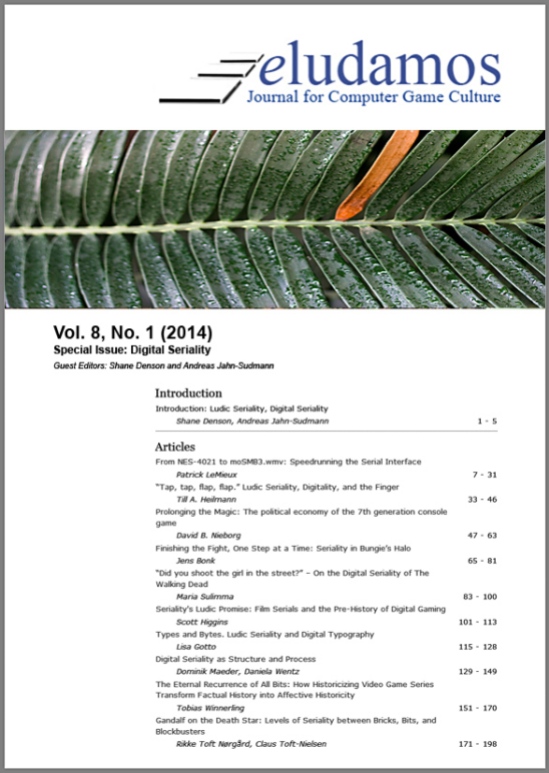

Denson, Shane, and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann, eds. Digital Seriality. Special issue. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 8.1 (2014). http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/issue/view/vol8no1

Kelleter, Frank, ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2012.

The latest issue of Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, a special issue devoted to the topic of “Digital Seriality” — edited by yours truly, together with Andreas Jahn-Sudmann — is now out! Weighing in at 198 pages, this is one of the fattest issues yet of the open-access journal, and it’s jam-packed with great stuff like:

- Patrick LeMieux on the culture and technology of tool-assisted speedrunning

- Jens Bonk on the serial structure of Halo

- Scott Higgins on the ludic pre-history of gaming in serial films

- Lisa Gotto on ludic seriality and digital typography

- Tobias Winnerling on the serialization of history in “historical” games

- Till Heilmann on Flappy Bird and the seriality of digits

- David B. Nieborg on the political economy of blockbuster games

- Rikke Toft Nørgård and Claus Toft-Nielsen on LEGO as an environment for serial play

- Dominik Maeder and Daniela Wentz on serial interfaces and memes

- Maria Sulimma on cross-medium serialities in The Walking Dead!

So what are you waiting for? Do yourself a favor and check out this issue now!

I am pleased to announce that my colleague Andreas Jahn-Sudmann and I will be co-editing a special issue of Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture on the topic of “Digital Seriality.” Here, you’ll find the call for papers (alternatively, you can download a PDF version here). Please circulate widely!

Call for Papers: Digital Seriality

Special Issue of Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture (2014)

Edited by Shane Denson & Andreas Jahn-SudmannAccording to German media theorist Jens Schröter, the analog/digital divide is the “key media-historical and media-theoretical distinction of the second half of the twentieth century” (Schröter 2004:9, our translation). And while this assessment is widely accepted as a relatively uncontroversial account of the most significant media transformation in recent history, the task of evaluating the distinction’s inherent epistemological problems is all the more fraught with difficulty (see Hagen 2002, Pias 2003, Schröter 2004). Be that as it may, since the 1990s at the latest, virtually any attempt to address the cultural and material specificity of contemporary media culture has inevitably entailed some sort of (implicit or explicit) evaluation of this key distinction’s historical significance, thus giving rise to characterizations of the analog/digital divide as caesura, upheaval, or even revolution (Glaubitz et al. 2011). Seen through the lens of such theoretical histories, the technical and especially visual media that shaped the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (photography, film, television) typically appear today as the objects of contemporary digitization processes, i.e. as visible manifestations (or remnants) of a historical transition from an analog (or industrial) to a digital era (Freyermuth and Gotto 2013). Conversely, despite its analog pre-history today’s digital computer has primarily been addressed as the medium of such digitization processes – or, in another famous account, as the end point of media history itself (Kittler 1986).

The case of digital games (as a software medium) is similar to that of the computer as a hardware medium: although the differences and similarities between digital games and older media were widely discussed in the context of the so-called narratology-versus-ludology debate (Eskelinen 2001; Juul 2001; Murray 1997, 2004; Ryan 2006), only marginal attention was paid in these debates to the media-historical significance of the analog/digital distinction itself. Moreover, many game scholars have tended to ontologize the computer game to a certain extent and to treat it as a central form or expression of digital culture, rather than tracing its complex historical emergence and its role in brokering the transition from analog to digital (significant exceptions like Pias 2002 notwithstanding). Other media-historiographical approaches, like Bolter and Grusin’s concept of remediation (1999), allow us to situate the digital game within a more capacious history of popular-technical media, but such accounts relate primarily to the representational rather than the operative level of the game, so that the digital game’s “ergodic” form (Aarseth 1999) remains largely unconsidered.

Against this background, we would like to suggest an alternative angle from which to situate and theorize the digital game as part of a larger media history (and a broader media ecology), an approach that attends to both the representational level of visible surfaces/interfaces and the operative level of code and algorithmic form: Our suggestion is to look at forms and processes of seriality/serialization as they manifest themselves in digital games and gaming cultures, and to focus on these phenomena as a means to understand both the continuities and the discontinuities that mark the transition from analog to digital media forms and our ludic engagements with them. Ultimately, we propose, the computer game simultaneously occupies a place in a long history of popular seriality (which stretches from pre-digital serial literature, film, radio, and television, to contemporary transmedia franchises) while it also instantiates novel forms of a specifically digital type of seriality (cf. Denson and Jahn-Sudmann 2013). By grappling with the formal commensurabilities and differences that characterize digital games’ relations to pre-digital (and non-ludic) forms of medial seriality, we therefore hope to contribute also to a more nuanced account of the historical process (rather than event) of the analog/digital divide’s emergence.

Overall, seriality is a central and multifaceted but largely neglected dimension of popular computer and video games. Seriality is a factor not only in explicitly marked game series (with their sequels, prequels, remakes, and other types of continuation), but also within games themselves (e.g. in their formal-structural constitution as an iterative series of levels, worlds, or missions). Serial forms of variation and repetition also appear in the transmedial relations between games and other media (e.g. expansive serializations of narrative worlds across the media of comics, film, television, and games, etc.). Additionally, we can grasp the relevance of games as a paradigm example of digital seriality when we think of the ways in which the technical conditions of the digital challenge the temporal procedures and developmental logics of the analog era, e.g. because once successively appearing series installments are increasingly available for immediate, repeated, and non-linear forms of consumption. And while this media logic of the database (cf. Manovich 2001: 218) can be seen to transform all serial media forms in our current age of digitization and media convergence, a careful study of the interplay between real-time interaction and serialization in digital games promises to shed light on the larger media-aesthetic questions of the transition to a digital media environment. Finally, digital games are not only symptoms and expressions of this transition, but also agents in the larger networks through which it has been navigated and negotiated; serial forms, which inherently track the processes of temporal and historical change as they unfold over time, have been central to this media-cultural undertaking (for similar perspectives on seriality in a variety of media, cf. Beil et al. 2013, Denson and Mayer 2012, Jahn-Sudmann and Kelleter 2012, Kelleter 2012, Mayer 2013).

To better understand the cultural forms and affective dimensions of what we have called digital games’ serial interfacings and the collective serializations of digital gaming cultures (cf. Denson and Jahn-Sudmann 2013), and in order to make sense of the historical and formal relations of seriality to the emergence and negotiation of the analog/digital divide, we seek contributions for a special issue of Eludamos: Journal of Computer Game Culture on all aspects of game-related seriality from a wide variety of perspectives, including media-philosophical, media-archeological, and cultural-theoretical approaches, among others. We are especially interested in papers that address the relations between seriality, temporality, and digitality in their formal and affective dimensions.

Possible topics include, but are not limited to:

- Seriality as a conceptual framework for studying digital games

- Methodologies and theoretical frameworks for studying digital seriality

- The (im)materiality of digital seriality

- Digital serialities beyond games

- The production culture of digital seriality

- Intra-ludic seriality: add-ons, levels, game engines, etc.

- Inter-ludic seriality: sequels, prequels, remakes

- Para-ludic seriality: serialities across media boundaries

- Digital games and the limits of seriality

******************************************************************************

Paper proposals (comprising a 350-500 word abstract, 3-5 bibliographic sources, and a 100-word bio) should be sent via e-mail by March 1, 2014 to the editors:

- a.sudmann[at]fu-berlin.de

- shane.denson[at]engsem.uni-hannover.de

Papers will be due July 15, 2014 and will appear in the fall 2014 issue of Eludamos.

*******************************************************************************

References:

Aarseth, Espen. 1999. “Aporia and Epiphany in Doom and The Speaking Clock: The Temporality of Ergodic Art.” In Marie-Laure Ryan, ed. Cyberspace Textuality: Computer Technology and Literary Theory. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 31–41.

Beil, Benjamin, Lorenz Engell, Jens Schröter, Daniela Wentz, and Herbert Schwaab. 2012. “Die Serie. Einleitung in den Schwerpunkt.” Zeitschrift Für Medienwissenschaft 2 (7): 10–16.

Bolter, J. David, and Richard A, Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Denson, Shane, and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann. “Digital Seriality: On the Serial Aesthetics and Practice of Digital Games.” Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture 1 (7): 1-32. http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/vol7no1-1/7-1-1-html.

Denson, Shane, and Ruth Mayer. 2012. “Grenzgänger: Serielle Figuren im Medienwechsel.” In Frank Kelleter, ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, 185-203.

Eskelinen, Markku. 2001. “The Gaming Situation” 1 (1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/.

Freyermuth, Gundolf S., and Lisa Gotto, eds. 2012. Bildwerte: Visualität in der digitalen Medienkultur. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Glaubitz, Nicola, Henning Groscurth, Katja Hoffmann, Jörgen Schäfer, Jens Schröter, Gregor Schwering, and Jochen Venus. 2011. Eine Theorie der Medienumbrüche. Vol. 185/186. Massenmedien und Kommunikation. Siegen: Universitätsverlag Siegen.

Hagen, Wolfgang. 2002. “Es gibt kein ‘digitales Bild’: Eine medienepistemologische Anmerkung.” In: Lorenz Engell, Bernhard Siegert, and Joseph Vogl, eds. Archiv für Mediengeschichte Vol. 2 – “Licht und Leitung.” München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 103–12.

Jahn-Sudmann, Andreas, and Frank Kelleter. “Die Dynamik Serieller Überbietung: Zeitgenössische Amerikanische Fernsehserien und das Konzept des Quality TV.” In Frank Kelleter, ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, 205–24.

Juul, Jesper. 2001. “Games Telling Stories? – A Brief Note on Games and Narratives.” Game Studies 1 (1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/juul-gts/.

Kelleter, Frank, ed. 2012. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion: Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Kittler, Friedrich A. 1986. Grammophon, Film, Typewriter. Berlin: Brinkmann & Bose.

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Mayer, Ruth. 2013. Serial Fu Manchu: The Chinese Supervillain and the Spread of Yellow Peril Ideology. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Murray, Janet H. 1997. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Murray, Janet H. 2004. “From Game-Story to Cyberdrama.” In Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan, eds. First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2-10.

Pias, Claus. 2002. Computer Spiel Welten. Zürich, Berlin: Diaphanes.

Pias, Claus. 2003. “Das digitale Bild gibt es nicht. Über das (Nicht-)Wissen der Bilder und die informatische Illusion.” Zeitenblicke 2 (1). http://www.zeitenblicke.de/2003/01/pias/.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2006. Avatars of Story. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schröter, Jens. 2004. “Analog/Digital – Opposition oder Kontinuum?” In Jens Schröter and Alexander Böhnke, eds. Analog/Digital – Opposition oder Kontinuum? Beiträge zur Theorie und Geschichte einer Unterscheidung. Bielefeld: Transcript, 7–30.

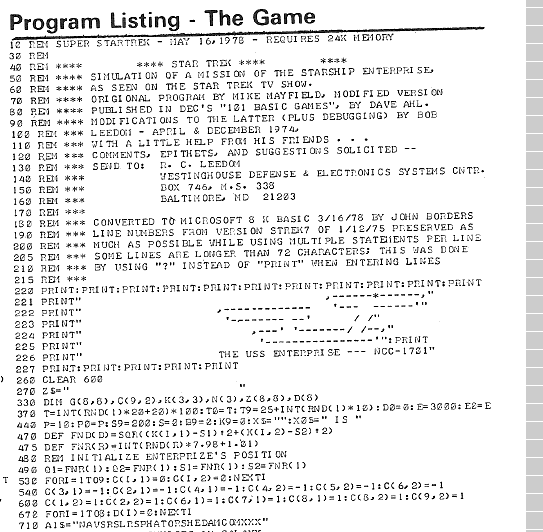

Here’s a sneak peek at something I’ve been working on for a jointly authored piece with Andreas Jahn-Sudmann (more details soon!):

[…] whereas the relatively recent example of bullet time emphasizes the incredible speed of our contemporary technical infrastructure, which threatens at every moment to outstrip our phenomenal capacities, earlier examples often mediated something of an inverse experience: a mismatch between the futurist fantasy and the much slower pace necessitated by the techno-material realities of the day.

The example of Super Star Trek (1978) illuminates this inverse sort of experience and casts a media-archaeological light on collective serialization, by way of the early history of gaming communities and their initially halting articulation into proto-transmedia worlds. Super Star Trek was not the first – and far from the last – computer game to be based on the Star Trek media franchise (which encompasses the canonical TV series and films, along with their spin-offs in comics, novels, board games, role-playing games, and the larger Trekkie subculture). Wikipedia lists over seventy-five Trek-themed commercial computer, console, and arcade games since 1971 (“History of Star Trek Games”) – and the list is almost surely incomplete. Nevertheless, Super Star Trek played a special role in the home computing revolution, as its source code’s inclusion in the 1978 edition of David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games was instrumental in making that book the first million-selling computer book.[i] The game would continue to exert a strong influence: it would go on to be packaged with new IBM PCs as part of the included GW-BASIC distribution, and it inspired countless ports, clones, and spin-offs in the 1980s and beyond.

A quick look at the game’s source code reveals that Super Star Trek didn’t just come out of nowhere, however: Here, the opening comment lines (“REM” indicates a non-executable “remark” in BASIC) mention not only the “Star Trek TV show” as an influence, but also a serial trajectory of inter-ludic programming, modification, debugging, and conversion (porting) that begins to outline a serialized collectivity of sorts. Beyond those participants mentioned by name (Mike Mayfield, David Ahl, Bob Leedom, and John Borders), a diffuse community is invoked – “with a little help from his friends…” – and, in fact, solicited: “comments, epithets, and suggestions” are to be sent personally to R. C. Leedom at Westinghouse Defense & Electronics. Reminiscent of a comic-book series’ “letters to the editor” page (cf. Kelleter and Stein 2012), this invitation promises, in conjunction with the listing of the game’s serial lineage, that readers’ opinions are valued, and that significant contributions will be rewarded (or at least honored with a hat-tip in the REM’s). Indeed, in these few preliminary lines, the program demonstrates its common ground with serialized production forms across media: since the nineteenth century, readers have written to the authors of ongoing series in order to praise or condemn – and ultimately to influence – the course of serial unfolding (cf. Hayward 1997, Looby 2004, Smith 1995, Thiesse 1980); authors dependent on the demands of a commercial marketplace were not at liberty simply to disregard their audience’s wishes, even if they were free to filter and select from among them. What we see, then, from an actor-network perspective, is that popular series therefore operate to create feedback loops in which authors and readers alike are involved in the production of serial forms (cf. Kelleter 2012a) – which therefore organize themselves as self-observing systems around which serialized forms of (para-)social interaction coalesce (cf. Kelleter 2012d, as well as the contributions to Kelleter 2012b).

The snippet of code above thus attests to the aspirations of a germinal community of hackers and gamers, which has tellingly chosen to align itself, in this case, with one of the most significant and quickly growing popular-culture fan communities of the time: viz. the Trekkie subculture, which can be seen to constitute a paradigmatic “seriality” in Anderson’s sense – a nation-like collective (complete with its own language) organized around the serialized consumption of serially structured media. And, indeed, the computing/gaming community had its own serialized media (and languages) through which it networked, including a plethora of computer-listings newsletters and magazines – such as David Ahl’s Creative Computing, where Super Star Trek had been published in 1974, before BASIC Computer Games made it more widely known; or People’s Computer Company, where Bob Leedom had mentioned his version before that; or the newsletter of the Digital Equipment Computer User Society, where Ahl had originally published a modified version of Mike Mayfield’s program. These publications served purposes very much like the comic-book and fanzine-type organs of other communities; here, however, it was code that was being published and discussed, thus serving as a platform for further involvement, tweaking, and feedback by countless others. Accordingly, behind the relatively linear story of development told in the REM’s above, there was actually a sprawling, non-linear form of para-ludic serialization at work in the development of Super Star Trek.[ii]

And yet we see something else here as well: despite the computing industry’s undeniable success in moving beyond specialized circles and involving ever larger groups of people in the activity of computing in the 1970s (and gaming must certainly be seen as central to achieving this success), the community described above was still operating with relatively crude means of collective serialization – more or less the same paper-bound forms of circulation that had served the textual and para-textual production of popular serialities since the nineteenth century. In many ways, this seems radically out of step with the space-age fantasy embodied in Super Star Trek: in order to play the game, one had to go through the painstaking (and mistake-prone) process of keying in the code by hand. If, afterwards, the program failed to run, the user would have to search for a misspelled command, a missing line, or some other bug in the system. And God forbid there was an error in the listing from which one was copying! Moreover, early versions of the game were designed for mainframe and minicomputers that, in many cases, were lacking a video terminal. The process of programming the game – or playing it, for that matter – was thus a slow process made even slower by interactions with punch-card interfaces. How, under these conditions, could one imagine oneself at the helm of the USS Enterprise? There was a mismatch, in other words, between the fantasy and the reality of early 1970s-era computing. But this discrepancy, with its own temporal and affective dynamics, was a framing condition for a form of collective serialization organized along very different lines from contemporary dreams of games’ seamless integration into transmedia worlds.

To begin with, it is quite significant that Super Star Trek’s functional equivalent of the “letters to the editor” page, where the ongoing serialization of the game is both documented and continued, is not printed in an instruction manual or other accompanying paraphernalia but embedded in the code itself. In contrast to the mostly invisible code executed in mainstream games today, Super Star Trek’s code was regarded as highly visible, the place where early gamers were most likely to read the solicitation to participate in a collective effort of development. Clearly, this is because they would have to read (and re-write) the code if they wished to play the game – while their success in actually getting it to work were more doubtful. Gameplay is here subordinated to coding, while the pleasures of both alike were those of an operational aesthetic: whether coding the game or playing it, mastery and control over the machine were at stake. Unlike the bullet time of The Matrix or Max Payne, which responds to an environment in which gamers (and others) are hard-pressed to keep up with the speed of computation, Super Star Trek speaks to a somewhat quainter, more humanistic dream of getting a computational (or intergalactic) jalopy up and running in the first place. In terms of temporal affectivities, patience is tested more so than quick reactions. If bullet time slowed down screen events while continuing to poll input devices as a means for players to cope with high-velocity challenges, the tasks of coding and playing Super Star Trek turn this situation around: it is not the computer but the human user who waits for – hopes for – a response. As a corollary, however, relatively quick progress was observable in the game’s inter-ludic development, which responded to rapid innovations in hardware and programming languages. This fact, which corresponded well with the basically humanistic optimism of the Star Trek fantasy (as opposed to the basically inhuman scenario of The Matrix), motivated further involvement in the series of inter-ludic developments (programming, modification, debugging, conversion…), which necessarily involved coder/tinkerers in the para-ludic exchanges upon which a gaming community was being built. […]

[i] A more complete story of the game’s history can be gleaned from several online sources which we draw on here: Maury Markowitz’s page devoted to the game, “Star Trek: To boldly go… and then spawn a million offshoots,” at his blog Games of Fame (http://gamesoffame.wordpress.com/star-trek/) features comments and correspondence with some of the key figures in the game’s development; Pete Turnbull also recounts the game’s history, including many of the details of its many ports to various systems (http://www.dunnington.u-net.com/public/startrek/); atariarchives.org hosts a complete scan of the 1978 edition of BASIC Computer Games, from which we reproduce an excerpt below (http://www.atariarchives.org/basicgames/); and a recent article in The Register, Tony Smith’s “Star Trek: The Original Computer Game,” features several screenshots and code snippets of various iterations (http://www.theregister.co.uk/Print/2013/05/03/antique_code_show_star_trek/).

[ii] A better sense of this can be had by taking a look at all the various iterations of the game – encompassing versions for a variety of flavors of BASIC and other languages as well – collected by Pete Turnbull (http://www.dunnington.u-net.com/public/startrek/).

Works Cited

Hayward, J. (1997) Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera. Lexington: UP of Kentucky.

Kelleter, F. (2012a) Populäre Serialität: Eine Einführung. In Kelleter F., ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 11-46.

Kelleter, F., ed. (2012b) Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Kelleter, F. (2012d) The Wire and Its Readers. In Kennedy, L. and Shapiro, S., eds. “The Wire”: Race, Class, and Genre. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, pp. 33-70.

Kelleter, F. and Stein, D. (2012) Autorisierungspraktiken seriellen Erzählens: Zur Gattungsentwicklung von Superheldencomics. In Kelleter, F., ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 259-290.

Looby, C. (2004) Southworth and Seriality: The Hidden Hand in the New York Ledger. Nineteenth-Century Literature 59.2, pp. 179-211.

Smith, S. B. (1995) Serialization and the Nature of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In Price, K. M. and Smith, S. B., eds. Periodical Literature in Nineteenth-Century America. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, pp. 69-89.

Thiesse, A.-M. (1980) L’education sociale d’un romancier: le cas d’Eugène Sue. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 32-33, pp. 51-63.