Above, you’ll find a video presentation of my talk, “Animation as Theme and Medium: Frankenstein and Visual Culture,” which I gave on April 20, 2013 at Dartmouth College — at the great Illustration, Comics, and Animation conference masterfully organized by Michael A. Chaney. Judging by the feedback I received at the time, my talk went over quite well — especially the visual presentation with which I illustrated my arguments (and particularly the “wall” of Frankenstein images you’ll see around 6:03, as well as the animated presentation of Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein series from about 12:52 onward).

(Note that a high-resolution video can be found by following the link to YouTube.)

Admittedly, the screencast video presentation is a weird medium. It tends to foreground things that, when presented live, serve as background images — images that are positioned above and behind a human speaker, talking and gesticulating, communicating (at least ideally) with an audience. In the screencast video, that speaker vanishes into the disembodied ether of a voiceover track, at times leaving images (like the title slide here) lingering on screen longer than might seem appropriate. Perhaps I haven’t yet mastered the medium and discovered a way to achieve the elegance we see in video essays, documentaries, and other related media; or perhaps the screencast video is simply doomed to be a forever awkward, weird, transitional, or incomplete medium.

In any case, the form is not everyone’s cup of tea, and an exemplar like this one is certainly pushing the limits at just over 18 minutes long. As a result, I have taken several steps to make sure that the video is as watchable and as useful as possible for anyone who might be interested in the arguments I make about Frankenstein, film, comics, animation, and visual culture. First, at the cosmetic level, I’ve added some music to deflect attention from my voice and to make the video a bit less “dry” than it otherwise might be (see below for music credits). Also, I have chosen to include the full text of the paper here, which you will find below; this way, you can skim, scan, and search, and “try before you buy” if you like, or decide what parts of the video you’d like to watch. Also, I offer a sort of “table of contents” to the video, with approximate times indicated for the various topics discussed:

0:00 — Introduction: Animation as Theme and Medium

1:30 — Animation as Framing Condition for Modern Visual Culture

4:28 — Frankenstein’s Monster as Iconic Emblem of Animation

5:30 — The Early Proliferation of the Monster’s Image

6:03 — The Plurimedial Explosion of Images and the Visual Serialization of the Monster (illustrated by the “wall” of images that many saw as the central visual attraction of the presentation itself)

7:40 — Frankenstein Films, Self-Reflexivity, and Animation

8:53 — Thomas Edison’s Frankenstein (1910)

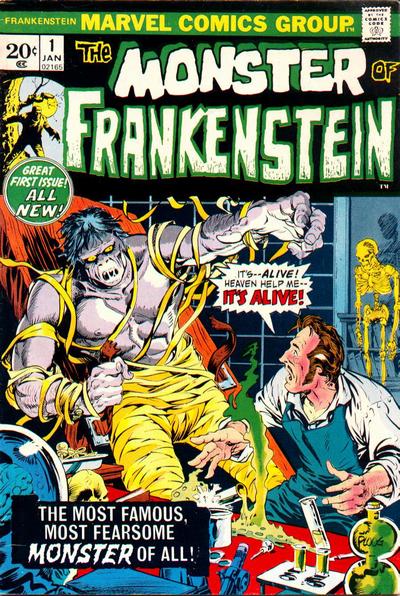

12:52 — Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein (1973 – 1975)

17:25 — Conclusion

The presentation draws on several previous works, including Chapter 3 of my dissertation (on Edison’s Frankenstein) and an article called “Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein: A Case Study in the Media of Serial Figures” — so be sure to check those out if anything is of interest to you here.

Here is the text of the talk:

Animation as Theme and Medium: Frankenstein and Visual Culture

Shane Denson – Dartmouth College, April 20, 2013

Long marginalized in critical discourses, animation seems to occupy an unprecedented position in our popular and visual cultures today. It has been argued, for instance, that in the age of digital cinema all film becomes animated film as photographic images’ indexical relations to the world are severed by processes of digital rendering. And not only film: comics, too, seem to be caught in the tractor beam of animation – partly as a result of general convergence trajectories and partly as a result of specific transmedia franchising efforts that place ever more superheroes in sleek new CGI outfits. Simultaneously, comics proper migrate from paper to digital formats and devices, bringing with them animation processes as elements of images and of presentation formats (like the “guided view” function on iPhone apps, which animate the transition from panel to panel). But if it’s true that the boundaries between animation and other forms of visual media have become problematic in the digital age, I want to suggest that this is not entirely new. My aim is therefore to open up a sort of media archaeological perspective that will allow us to look at animation as both a theme and a medium that plays a significant if non-obvious role throughout the modern era. Drawing on retellings of Frankenstein in film and comics, I argue that the tale’s serial proliferation reveals a hidden backstory to our current situation, one in which animation can be seen as the very framing condition for much of our modern popular visual culture.

By emphasizing modernity and popularity, the visual culture I’m talking about is connected explicitly to industrialization, which coincided with the institution of a conceptual wedge between art and technology – i.e. between the fine arts and the applied arts – such that aesthetic experience was figured as “disinterested” and opposed to the realms of practical technology and commercial culture. And out of the industrial-era reorganizations within the broad realm of technē flow a variety of fears and fantasies of technical animation (embodied in automata like the Mechanical Turk, and in narratives such as E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann” and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein). Such thematic concerns with “animation” – or the giving of life to inanimate matter – would have a lasting impact on (popular/visual) culture as the arts became increasingly technical, industrial, reproducible, and (in more senses than one) serialized; from Metropolis to Blade Runner and beyond, the dream of artificial life has been a staple of science-fiction film. But beyond the thematic level, a medial aspect or determination of “animation” is also involved: not only was the technical infrastructure of steam-driven printing presses, automata, and pre-cinematic devices uncanny in its liveliness and activity; also, at the dawn of the industrial age, the fine arts were framed in such a way as to marginalize animation as a possible medium. Lessing’s famous division of temporal and spatial arts (with poetry, drama, and narrative on the one side, sculpture, painting, and image on the other) preemptively banished a range of popular forms from the domain of serious art. But against these injunctions of aesthetic purity, post-industrial visual culture is characterized by a preponderance of images that spring to life as they are set in motion and animated by mechanical means. Film and comics, most centrally, would blur the boundaries between the static image and the temporal flow of narration. Generally and conceptually speaking, if not narrowly and technically, “animation” names these media’s affront to the division of the arts – their violation both of the division between temporal and spatial arts and of their separation from the merely technical and commercial domain of modern popular culture. This is another way of saying that animation, broadly conceived, is a sort of framing condition for modern visual culture, which can be seen in constant struggle with the image granted life or set in motion, alternately advancing toward and retreating from the conceptual and technological threat of visual kinesis that aesthetics as such was born in order to contain.

Seen in this way, modern visual culture’s ambivalent relation to animation is not altogether different from Frankenstein’s initial fascination with and sudden repulsion by the creature he brought to life. And it is the creature, of course, who provides the iconic emblem of animation as a monstrous threat. I want to argue that this image embodies both the thematic and the medial aspects of animation that I’ve been discussing, and it self-reflexively probes animation’s role in a visual culture that is both technological and remarkably autonomous in its ability to multiply images across various channels or media. Exhibiting a promiscuous, plurimedial sort of seriality, the monster’s image – as an image of animation – presents a special case for thinking the dynamic intermedial networks that constitute our visual culture. Cinema gives us the “classic” version of the monster’s image, but the figure’s visual proliferation has a serial history that predates the cinema and lives on in other forms as well. At the center of visual interest is the creation scene, which Shelley’s novel of 1818 treats only in a very cursory manner, but which gives rise immediately to a growing number of theatrical adaptations. Shelley herself saw a performance of Richard Brinsley Peake’s 1823 play Presumption; or the Fate of Frankenstein, and thus witnessed her tale escaping her authorial control much as the story’s monster had escaped its creator’s, prompting her famously in the introduction to the 1831 edition of her book to “bid [her] hideous progeny go forth and prosper.” The image on the frontispiece of the 1831 edition thus entered into a stream of visual images proliferating on theater stages, in political cartoons, and later in film, comics, and other media. Taken together, these images are not, I suggest, just illustrations of a story but themselves enactments of a media-technical interrogation of modern processes of animation and the self-replicating action of our visual culture. Essential to this view is a conception of the monster not so much as a developed character but as a flat, serialized figure that has escaped the novel and acquired a life of its own. As such, the monster is marked materially by a form of seriality that is intimately tied to the serial production processes of industrial culture and, more specifically, to the sequentiality and reproducibility of images in modern visual media such as film and comics. Appearing again and again in various media, the monster becomes what I call a serial figure, existing not within a series but in fact as a series – as the expanding set of stagings or instantiations across media. The monster thus evolves not within a uniform diegetic space, but between or across such spaces of narration and visualization. As a serial figure, the monster leads a sort of surplus existence outside of any one given telling, thus placing it in a perfect position to reflect on the manner – and the media – of its repeated stagings. Specifically, it explores modern visual culture’s challenge to the inert spatial image, its tendency to transgress the injunction against animation. The familiar cry – “It’s alive!” – thus refers as much to the media of sequential and temporal images as it does to the creature they depict.

Let’s start with Frankenstein films. There’s a sense in which it’s tempting to see film itself as a sort of Frankensteinian technology. Like Frankenstein selecting parts from corpses and infusing life into a composite body, filmmakers utilize the technical means of film to (re)animate the “dead” (or photographically preserved) traces of living organisms (actors) into new visual narrative compositions. In his discussion of Frankenstein films, William Nestrick writes: “The film is the animation of the machine, a continuous life created by the persistence of vision in combination with a machine casting light through individual photographs flashed separately upon the screen. Since ‘life’ in film is movement, the word that bridges the worlds of film and man is ‘animation’ – the basic principle by which motion is imparted to the picture” (294-95). It will be objected, however, that this invitingly simple analogy is too general in its scope; it overlooks historically specific transformations in the way such “animation” has been staged. Luckily, the long history of Frankenstein adaptations amply documents such changes and makes up for the missing nuance.

Take, for instance, Thomas Edison’s Frankenstein from 1910, which stands between the early, image-technology oriented “cinema of attractions” and the coming narrative-oriented classical Hollywood style that would take shape around 1917. In 1910, the medium was in transition, torn between lowbrow technological spectacle and an uncertain reorientation along the lines of the respectable theater. Accordingly, advertising for the film emphasized both the “photographic marvel” of the creation sequence and the story’s origin in “Mrs. Shelley’s […] work of art.” The film aimed to be both visual and technological spectacle and narrative high culture. And this multiple address relates directly to the uncertain significance of “animation” at this historical juncture.

The creation sequence’s so-called “marvel” consists of footage of a burning mannequin projected in reverse – a bit of cinematic magic that, in the context of early film, served to exhibit cinematic technology by focusing attention on the filmic images themselves rather than the objects they depict. Frankenstein’s reactions here channel the scopophilic pleasure of a “primitive” viewer, for whom he stands in as a proxy. Importantly, “animation” here is a self-reflexive topos which links the monster’s creation with the term “animated photography,” still common in 1910 as a description of film in general.

However, the final showdown ambivalently signals a change of course towards narrative integration. The Edison Company claims that the scene communicates the story’s moral that love conquers all. But since the monster was identified with filmic technology in the creation sequence, Frankenstein’s battle with the monster is also with the medium of film as an animating technology, especially since trick effects are essential to the staging of the conflict. The film’s narrative closure is therefore mixed with a self-reflexive countercurrent. The mirror functions here like the projection surface of the cinema screen. The similarity is not merely abstract but in fact visually perceptible due to the scene’s technical means of production: the images in the mirror are themselves flickering filmic images. The result is a film within the film, and Frankenstein is again a film viewer. His battle with the monster is a battle with the images and especially with the “primitive” type of reception that he exemplified in the creation sequence. But this time he is reformed, and instead of staring at the medial surface, he now acquires the ability to look through rather than at the mirror. So Frankenstein is finally in a position to devote his attentions to the reality of his environment – which means, for us, to the world of the diegesis.

In the context of the cinema’s transitional phase, the film’s narrative development is linked to a larger, non-diegetic narrative of filmic development: Frankenstein’s psychological maturation, which is consummated in the mirror scene, allegorizes a historical-normative process of cinematic maturation and of spectatorial progress towards a proto-classical relation to film. And significantly, this transitional trajectory coincided with the historical differentiation of film, or “animated photography,” according to which animation in the narrower sense came to be distinguished from, and subordinated to, a more respectable form of live-action filmmaking that favored drama and characterization over novelty gags and trick-film effects. The monster, a literal product of animation, charts this differentiation at the same moment people like Winsor McCay were popularizing techniques of animation in its narrower sense. Thus, the monster embodies the technology of the animated spectacle, and his marginalization reflexively indicates the framing function of animation in film and visual culture more generally, reminding us that live-action cinema is animation too, but in a normalized or naturalized form.

Now I want to jump ahead to a comic-book appropriation that offers a somewhat different perspective on animation as theme and medium owing to its reflexive engagement with the formal properties of graphic narrative. Here the monster is recalibrated for an interrogation of the specific means by which comics animate their tales – that is, the means by which discrete images both remain discrete and are subject to combinatory reframings that bring a graphic story to life. Marvel’s series The Monster of Frankenstein (later retitled The Frankenstein Monster) ran for 18 issues from January 1973 to September 1975. The first four issues retell the tale of Shelley’s novel, and they reproduce its nested frame structure: the monster’s own tale is at the center, embedded in Frankenstein’s account of events, which he recounts to the Arctic explorer Captain Walton while aboard his ship; Walton, in turn, records everything and passes it along in the form of letters to his sister back home, and these letters make up the novel Frankenstein. Now the Marvel series, in its re-telling, ingeniously adds an additional frame: Walton IV, the great-grandson of the novel’s captain, narrates the outermost tale, set a full century after the novel, thus laying the ground for the story’s continuation into the twentieth century from issue #5 onward.

With an eye to the monster’s place in visual culture more generally, what interests me above all about this is the way that these various framings and reframings are navigated visually, and the role that the technically animated creature plays in the process. Issue #2 features several exemplary moments that I’d like to focus on. The monster’s tale is prefaced visually with a close-up of the monster’s face, which functions as a gateway or border between external and internal narrative frames (between the cave setting in which the monster relates his tale to Frankenstein and the innermost frame of the related tale) (6, panel 5). The creature tells how he came to his senses, how he observed a blind man and his family, learned their language, and was eventually driven from human society. Finally, his narrative closes with a close-up of the creature’s yellow eye in a wavy-bordered panel that exists liminally between one narrative frame and another (18, panel 3): Spatially attached both to the (self-narrated) monster persecuted by a mob of angry villagers and to the (narrating) monster in the mountain cave, the eye stands between and links the two temporal frames of narration. From this intermediate position, the monster’s eye mirrors the reader’s eye as well, the eye that moves from one graphic frame or panel to the next in the temporal process of reading. Emerging from the page in close-up and protruding from the narrated world to enter the space of the reader, this eye is medially self-reflexive in a strong sense: it directs attention towards the processes of medial construction at the same time that it serves a constructive medial purpose, viz. the transition from one visual and narrative frame to another. And something similar is staged several pages later. Having discovered the corpse of his friend Clerval, the traumatized Frankenstein is arrested for murder, and his face is foregrounded with a blank eye staring at—or through—the reader in a panel that transitions back to the outermost narrative frame, aboard Walton IV’s ship in 1898 (25, panel 4), which suddenly rams an iceberg and begins to sink, bringing issue #2 to a cliffhanger close.

At the outset of the next issue, sailors scramble into lifeboats in the belief that the monster, thrown overboard in the crash, is dead. But when the monster, whose hand juts ominously out of the water, boards their boat and begins wreaking havoc, one of the sailors exclaims, “God help us! It’s still alive!” (3)—an intensification of the standard line in Frankenstein films, fully self-aware of its seriality. Sparing the captain, his cabin-boy, and his guide, the monster rows them to firm ice. There, the monster insists: “The story, man! You must tell me the rest of the story!” (5). Then, with his back turned, Walton IV prepares to continue the narrative, while the monster’s face, set in profile, literally replaces the gutter between two panels and forms the border between two spatiotemporal frames as well: the “here and now” that he shares with Walton IV and the “there and then” of Walton’s story (6, panels 1 and 2). Once again, the monster’s face and eyes mediate the threshold between narrative frames, between temporal settings, and between the act and the content of mediation.

In conclusion, then, Frankenstein’s monster functions variously, as we have seen in these examples from film and comics, to envision the dynamic workings of modern visual culture. The creature doubles with the medium in order to envision visuality itself in its modern, highly kinetic forms. It gives visible form, in other words, to the invisible framing condition of animation, exposing the mechanisms by which static images routinely transgress their spatial borders and assert a temporal dimension, and exploring the role of mediating technologies in the serialized proliferations of images that animate the modern visual landscape.

Finally, here are the music credits for the video (all songs licensed with Creative Commons licenses and made available via dig.ccmixter.org):

1.  Constructions normales (Je ne suis pas un remix) by vo1k1 is licensed under a Noncommercial Sampling Plus (the song begins at 0:00 in the video);

Constructions normales (Je ne suis pas un remix) by vo1k1 is licensed under a Noncommercial Sampling Plus (the song begins at 0:00 in the video);

2.  Sawmill by Gurdonark is licensed under a Attribution (3.0) (beginning ca. 4:04);

Sawmill by Gurdonark is licensed under a Attribution (3.0) (beginning ca. 4:04);

3. pling by jaspertine is licensed under a Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) (beginning ca. 7:03);

pling by jaspertine is licensed under a Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) (beginning ca. 7:03);

4.  Yiourgh by DoKashiteru is licensed under a Sampling Plus (beginning ca. 12:18);

Yiourgh by DoKashiteru is licensed under a Sampling Plus (beginning ca. 12:18);

5.  Prism in the Ether by Fireproof_Babies is licensed under a Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) (beginning ca. 16:17).

Prism in the Ether by Fireproof_Babies is licensed under a Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) (beginning ca. 16:17).