The schedule has now been posted for the Illustration, Comics, and Animation Conference taking place this spring at Dartmouth College (April 19 – 21, 2013). There are quite a few interesting speakers and exciting topics on the roster, so I encourage readers to look at the complete conference schedule. But here I’d like to focus briefly on a few people who happen to be both involved in the conference and associated in one way or another with this blog and the various projects represented here.

First of all, two of my European colleagues will be presenting papers:

Daniel Stein, co-editor with me on Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives and fellow postdoctoral researcher in the Popular Seriality group, will be presenting a paper called “Animating Batman: Serial Storytelling, Cartoon Animation, and the Multiplicities of Contemporary Superhero Comics.” (Click the title for his abstract.)

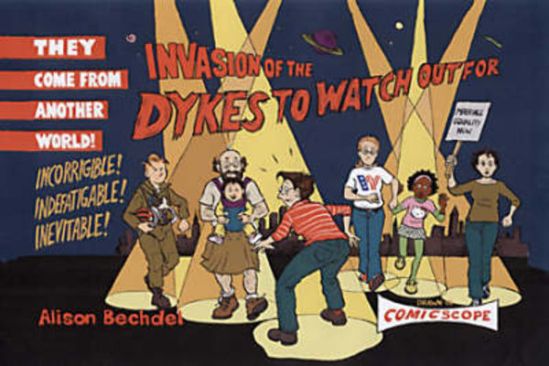

Lukas Etter, contributor to Transnational Perspectives (with a great chapter on Jason Lutes’s Berlin) and member of the research project “Seriality and Intermediality in Graphic Novels” (a Swiss project associated with the DFG research group on Popular Seriality), will present “Seria(s)lly Episodic: Gradual Formal Variations in Alison Bechdel’s Feminist Comic Strip Dykes to Watch Out For (1983-2008).” (Click title for abstract.)

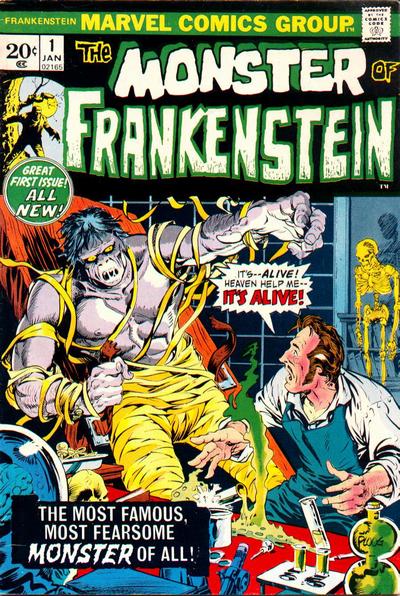

I will also be presenting a paper, titled “Animation as Theme and Medium: Frankenstein and Visual Culture.” (Again, click for the abstract.)

Finally, our American host and the conference’s organizer is Michael A. Chaney, Associate Professor of English at Dartmouth College, who is likewise a contributor to Transnational Perspectives (with an excellent chapter on “Transnationalism and Form in Visual Narratives of US Slavery”).

As it turns out, this will be the second time that all four of our paths cross — the first being at a comics studies workshop in Bern, Switzerland in October 2011. In this respect, and in addition to our cooperation on the volume, the upcoming conference marks the continuation of a very literal transnational exchange of ideas, which has brought together German, Swiss, and American (among other) perspectives on the study of comics and related media. I look forward to this and further such intersections and (national as well as medial) border-crossings!