Over at his blog, Michael A. Chaney (professor of English and American Studies at Dartmouth College and director of the Illustration, Comics, and Animation conference there) has posted an interview he conducted with Daniel Stein, Christina Meyer, and myself on the topic of comics and our edited collection Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives. Michael is a wonderful interviewer and an all-around great guy, and it was a lot of fun talking to him about our work. So take a look: here.

Tag: Shane Denson

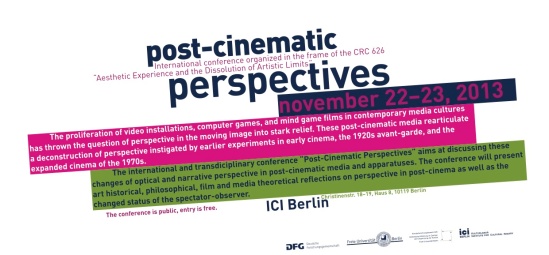

Post-Cinematic Perspectives

On November 22-23, 2013, I will be participating in the conference “Post-Cinematic Perspectives,” which is being organized by Lisa Åkervall and Chris Tedjasukmana at the Freie Universität Berlin. There’s a great line-up, as you’ll see on the conference program above. I look forward to seeing Steven Shaviro again (and hearing his talk on Spring Breakers), and to meeting all the other speakers. My talk, on the morning of the 23rd, is entitled “Nonhuman Perspectives and Discorrelated Images in Post-Cinema.” The conference is open to the public, and attendance is free.

Now Open Access: Bildstörung / Image Interference

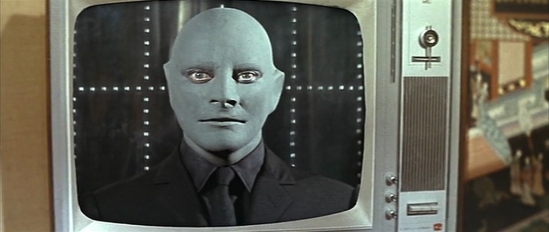

After appearing one year ago in Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft 7, the article “Bildstörung: Serielle Figuren und der Fernseher” [roughly, Image Interference: Serial Figures and the Television Set], co-authored by myself and Ruth Mayer, has now gone into open access and can be downloaded freely at the publisher’s website: here. In addition, the rest of the articles in this special issue devoted to “The Series” are now freely available here. I am very happy to be a part of this great collection, and I applaud ZfM‘s commitment to making their journals open access after an initial one-year print-only period.

Post-Cinematic Affect: Post-Continuity, the Irrational Camera, Thoughts on 3D

Last summer (2012), I participated in a roundtable discussion with Therese Grisham and Julia Leyda on the subject of “Post-Cinematic Affect: Post-Continuity, the Irrational Camera, Thoughts on 3D.” Drawing on Steven Shaviro’s book Post-Cinematic Affect, and looking at films such as District 9, Melancholia, and Hugo, the roundtable appeared in the multilingual online journal La Furia Umana (issue 14, 2012). For some reason, the LFU site has been down for a few weeks, and I have no information about whether or when it will be back up. Accordingly, I wanted to point out for anyone who is interested that you can still find a copy of the roundtable discussion here (as a PDF on my academia page). Enjoy!

Digital Film, Chaos Cinema, Post-Cinematic Affect: Thinking 21st Century Motion Pictures

Here’s the course description for a graduate-level course I’ll be teaching in the winter semester (October 2013 – February 2014) — a PDF of the full syllabus is embedded above:

Digital Film, Chaos Cinema, Post-Cinematic Affect: Thinking 21st Century Motion Pictures

Instructor: Shane Denson

Course Description:

In this seminar, we will try to come to terms with twenty-first century motion pictures by thinking through a variety of concepts and theoretical approaches designed to explain their relations and differences from the cinema of the previous century. We will consider the impact of digital technologies on film, think about the cultural contexts and aesthetic practices of contemporary motion pictures, and try to understand the experiential dimensions of spectatorship in today’s altered viewing conditions. In addition to preparing weekly readings, students will be expected to view a variety of films prior to each class meeting.

Course Themes and Objectives:

In this course, we set out from the apparent “chaos” that contemporary cinema often presents to us: the seemingly incoherent and unmotivated camerawork and editing, for example, by which many action films of the twenty-first century mark their departure from the “classical” norms of Hollywood-style narration and formal construction. From here, we seek to make sense more generally of cinema’s transformation in terms of new technologies and techniques (e.g. digital imaging processes, nonlinear editing, and attendant editing styles), in terms of new modes of cinematic distribution and reception (e.g. DVD, Blu-Ray, and streaming services, HD TVs, smartphones, and tablet computers, but also IMAX 3-D and similar transformations of the big screen), in terms of non-classical narrative styles (e.g. recursive, database-like, non-linear, and even non-sequitur forms of storytelling), and in terms of broader phenomenological and environmental shifts that inform our experience, our embodiment, and our subjectivity in the digital era.

Several key concepts will help to orient our thinking about twenty-first century cinema and its relation to earlier cinematic modes. The first is “chaos cinema,” a term which Matthias Stork popularized in a compelling set of video essays focused particularly on recent action cinema; beyond this context, however, Stork’s notion of “chaos” resonates with the feelings and fears of many critics and theorists in the face of digital-era cinema. This broader perception of chaos is sometimes traced back to the digital unmooring of images from the indexical referents to which photographic films remained tied; on this basis, the somewhat oxymoronic term “digital film” is often linked to an even more unsettling, because more basic, sense of chaos: according to some critics, the digital (and the moving images it produces and supports) is correlated with a sweeping transformation of human society and subjectivity itself. On the other hand, though, not all critics are similarly alarmed by digital-era chaos. David Bordwell’s concept of “intensified continuity” effectively denies the radical stylistic break announced in Stork’s analysis; Bordwell sees the newer films as perhaps faster and even more hectic than classical Hollywood fare, but basically constructed according to principles of classical continuity – just intensified. By way of contrast, Steven Shaviro’s notion of “post-continuity” – developed in the context of his analysis of “post-cinematic affect” – provides another view of contemporary moving image culture, one which links formal and aesthetic transformations not only with new technologies but also with broader social, cultural, and economic changes underway right now.

As we think through these and related concepts, we will engage a variety of recent movies from formal, phenomenological, affective, cultural, and environmental perspectives. We will seek to understand whether a radical change has taken place in recent cinema, to assess what its significance might be, and in this way begin to think through the implications of and for our viewing habits in the twenty-first century.

You can find more of my syllabi here: http://uni-hannover.academia.edu/ShaneDenson

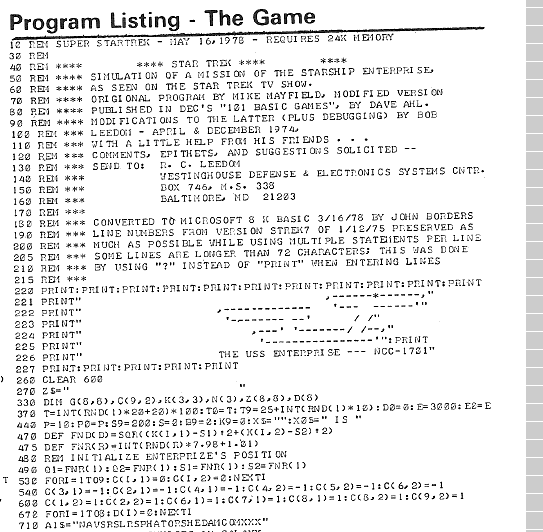

Super Star Trek and the Collective Serialization of the Digital

Here’s a sneak peek at something I’ve been working on for a jointly authored piece with Andreas Jahn-Sudmann (more details soon!):

[…] whereas the relatively recent example of bullet time emphasizes the incredible speed of our contemporary technical infrastructure, which threatens at every moment to outstrip our phenomenal capacities, earlier examples often mediated something of an inverse experience: a mismatch between the futurist fantasy and the much slower pace necessitated by the techno-material realities of the day.

The example of Super Star Trek (1978) illuminates this inverse sort of experience and casts a media-archaeological light on collective serialization, by way of the early history of gaming communities and their initially halting articulation into proto-transmedia worlds. Super Star Trek was not the first – and far from the last – computer game to be based on the Star Trek media franchise (which encompasses the canonical TV series and films, along with their spin-offs in comics, novels, board games, role-playing games, and the larger Trekkie subculture). Wikipedia lists over seventy-five Trek-themed commercial computer, console, and arcade games since 1971 (“History of Star Trek Games”) – and the list is almost surely incomplete. Nevertheless, Super Star Trek played a special role in the home computing revolution, as its source code’s inclusion in the 1978 edition of David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games was instrumental in making that book the first million-selling computer book.[i] The game would continue to exert a strong influence: it would go on to be packaged with new IBM PCs as part of the included GW-BASIC distribution, and it inspired countless ports, clones, and spin-offs in the 1980s and beyond.

A quick look at the game’s source code reveals that Super Star Trek didn’t just come out of nowhere, however: Here, the opening comment lines (“REM” indicates a non-executable “remark” in BASIC) mention not only the “Star Trek TV show” as an influence, but also a serial trajectory of inter-ludic programming, modification, debugging, and conversion (porting) that begins to outline a serialized collectivity of sorts. Beyond those participants mentioned by name (Mike Mayfield, David Ahl, Bob Leedom, and John Borders), a diffuse community is invoked – “with a little help from his friends…” – and, in fact, solicited: “comments, epithets, and suggestions” are to be sent personally to R. C. Leedom at Westinghouse Defense & Electronics. Reminiscent of a comic-book series’ “letters to the editor” page (cf. Kelleter and Stein 2012), this invitation promises, in conjunction with the listing of the game’s serial lineage, that readers’ opinions are valued, and that significant contributions will be rewarded (or at least honored with a hat-tip in the REM’s). Indeed, in these few preliminary lines, the program demonstrates its common ground with serialized production forms across media: since the nineteenth century, readers have written to the authors of ongoing series in order to praise or condemn – and ultimately to influence – the course of serial unfolding (cf. Hayward 1997, Looby 2004, Smith 1995, Thiesse 1980); authors dependent on the demands of a commercial marketplace were not at liberty simply to disregard their audience’s wishes, even if they were free to filter and select from among them. What we see, then, from an actor-network perspective, is that popular series therefore operate to create feedback loops in which authors and readers alike are involved in the production of serial forms (cf. Kelleter 2012a) – which therefore organize themselves as self-observing systems around which serialized forms of (para-)social interaction coalesce (cf. Kelleter 2012d, as well as the contributions to Kelleter 2012b).

The snippet of code above thus attests to the aspirations of a germinal community of hackers and gamers, which has tellingly chosen to align itself, in this case, with one of the most significant and quickly growing popular-culture fan communities of the time: viz. the Trekkie subculture, which can be seen to constitute a paradigmatic “seriality” in Anderson’s sense – a nation-like collective (complete with its own language) organized around the serialized consumption of serially structured media. And, indeed, the computing/gaming community had its own serialized media (and languages) through which it networked, including a plethora of computer-listings newsletters and magazines – such as David Ahl’s Creative Computing, where Super Star Trek had been published in 1974, before BASIC Computer Games made it more widely known; or People’s Computer Company, where Bob Leedom had mentioned his version before that; or the newsletter of the Digital Equipment Computer User Society, where Ahl had originally published a modified version of Mike Mayfield’s program. These publications served purposes very much like the comic-book and fanzine-type organs of other communities; here, however, it was code that was being published and discussed, thus serving as a platform for further involvement, tweaking, and feedback by countless others. Accordingly, behind the relatively linear story of development told in the REM’s above, there was actually a sprawling, non-linear form of para-ludic serialization at work in the development of Super Star Trek.[ii]

And yet we see something else here as well: despite the computing industry’s undeniable success in moving beyond specialized circles and involving ever larger groups of people in the activity of computing in the 1970s (and gaming must certainly be seen as central to achieving this success), the community described above was still operating with relatively crude means of collective serialization – more or less the same paper-bound forms of circulation that had served the textual and para-textual production of popular serialities since the nineteenth century. In many ways, this seems radically out of step with the space-age fantasy embodied in Super Star Trek: in order to play the game, one had to go through the painstaking (and mistake-prone) process of keying in the code by hand. If, afterwards, the program failed to run, the user would have to search for a misspelled command, a missing line, or some other bug in the system. And God forbid there was an error in the listing from which one was copying! Moreover, early versions of the game were designed for mainframe and minicomputers that, in many cases, were lacking a video terminal. The process of programming the game – or playing it, for that matter – was thus a slow process made even slower by interactions with punch-card interfaces. How, under these conditions, could one imagine oneself at the helm of the USS Enterprise? There was a mismatch, in other words, between the fantasy and the reality of early 1970s-era computing. But this discrepancy, with its own temporal and affective dynamics, was a framing condition for a form of collective serialization organized along very different lines from contemporary dreams of games’ seamless integration into transmedia worlds.

To begin with, it is quite significant that Super Star Trek’s functional equivalent of the “letters to the editor” page, where the ongoing serialization of the game is both documented and continued, is not printed in an instruction manual or other accompanying paraphernalia but embedded in the code itself. In contrast to the mostly invisible code executed in mainstream games today, Super Star Trek’s code was regarded as highly visible, the place where early gamers were most likely to read the solicitation to participate in a collective effort of development. Clearly, this is because they would have to read (and re-write) the code if they wished to play the game – while their success in actually getting it to work were more doubtful. Gameplay is here subordinated to coding, while the pleasures of both alike were those of an operational aesthetic: whether coding the game or playing it, mastery and control over the machine were at stake. Unlike the bullet time of The Matrix or Max Payne, which responds to an environment in which gamers (and others) are hard-pressed to keep up with the speed of computation, Super Star Trek speaks to a somewhat quainter, more humanistic dream of getting a computational (or intergalactic) jalopy up and running in the first place. In terms of temporal affectivities, patience is tested more so than quick reactions. If bullet time slowed down screen events while continuing to poll input devices as a means for players to cope with high-velocity challenges, the tasks of coding and playing Super Star Trek turn this situation around: it is not the computer but the human user who waits for – hopes for – a response. As a corollary, however, relatively quick progress was observable in the game’s inter-ludic development, which responded to rapid innovations in hardware and programming languages. This fact, which corresponded well with the basically humanistic optimism of the Star Trek fantasy (as opposed to the basically inhuman scenario of The Matrix), motivated further involvement in the series of inter-ludic developments (programming, modification, debugging, conversion…), which necessarily involved coder/tinkerers in the para-ludic exchanges upon which a gaming community was being built. […]

[i] A more complete story of the game’s history can be gleaned from several online sources which we draw on here: Maury Markowitz’s page devoted to the game, “Star Trek: To boldly go… and then spawn a million offshoots,” at his blog Games of Fame (http://gamesoffame.wordpress.com/star-trek/) features comments and correspondence with some of the key figures in the game’s development; Pete Turnbull also recounts the game’s history, including many of the details of its many ports to various systems (http://www.dunnington.u-net.com/public/startrek/); atariarchives.org hosts a complete scan of the 1978 edition of BASIC Computer Games, from which we reproduce an excerpt below (http://www.atariarchives.org/basicgames/); and a recent article in The Register, Tony Smith’s “Star Trek: The Original Computer Game,” features several screenshots and code snippets of various iterations (http://www.theregister.co.uk/Print/2013/05/03/antique_code_show_star_trek/).

[ii] A better sense of this can be had by taking a look at all the various iterations of the game – encompassing versions for a variety of flavors of BASIC and other languages as well – collected by Pete Turnbull (http://www.dunnington.u-net.com/public/startrek/).

Works Cited

Hayward, J. (1997) Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera. Lexington: UP of Kentucky.

Kelleter, F. (2012a) Populäre Serialität: Eine Einführung. In Kelleter F., ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 11-46.

Kelleter, F., ed. (2012b) Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Kelleter, F. (2012d) The Wire and Its Readers. In Kennedy, L. and Shapiro, S., eds. “The Wire”: Race, Class, and Genre. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, pp. 33-70.

Kelleter, F. and Stein, D. (2012) Autorisierungspraktiken seriellen Erzählens: Zur Gattungsentwicklung von Superheldencomics. In Kelleter, F., ed. Populäre Serialität: Narration – Evolution – Distinktion. Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 259-290.

Looby, C. (2004) Southworth and Seriality: The Hidden Hand in the New York Ledger. Nineteenth-Century Literature 59.2, pp. 179-211.

Smith, S. B. (1995) Serialization and the Nature of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In Price, K. M. and Smith, S. B., eds. Periodical Literature in Nineteenth-Century America. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, pp. 69-89.

Thiesse, A.-M. (1980) L’education sociale d’un romancier: le cas d’Eugène Sue. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 32-33, pp. 51-63.

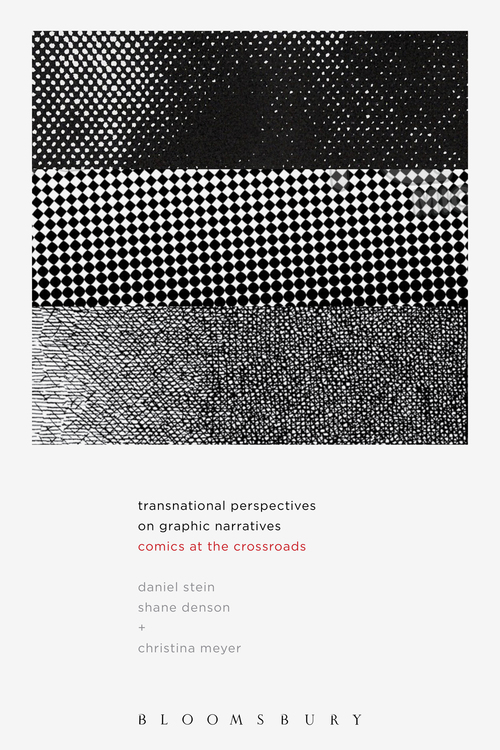

Transnational Comics Studies

Recently, I discovered an alternative cover concept — seen above — for Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads (which I co-edited along with Christina Meyer and Daniel Stein). I found this on the webpage of Daniel Benneworth-Gray, the designer who was also responsible for the final book cover. In the end, I have to say I like the final cover better, but I think this is a nice concept, and it gives me a kind of a parallel universe / Bizarro world / “What-if?” / retcon kinda feeling, which I think is quite appropriate for a book about comics.

Speaking of the book, Daniel Stein, Christina Meyer, and I will be doing just that: i.e. speaking about the book and the broader field of “Transnational Comics Studies” on October 9, at the Berliner Kolloquium zur Comicforschung. The meeting will take place at the Humboldt University in Berlin. I’ll post the exact time and place as soon as I know more.

Spectral Seriality: The Sights and Sounds of Count Dracula

Below you’ll find the talk that Ruth Mayer and I recently gave at the “Popular Seriality” conference in Göttingen (June 6-8, 2013). We will be expanding the paper for publication, so comments and criticisms are very welcome!

Spectral Seriality: The Sights and Sounds of Count Dracula

Shane Denson, Ruth Mayer – Leibniz Universität Hannover

1. Introduction

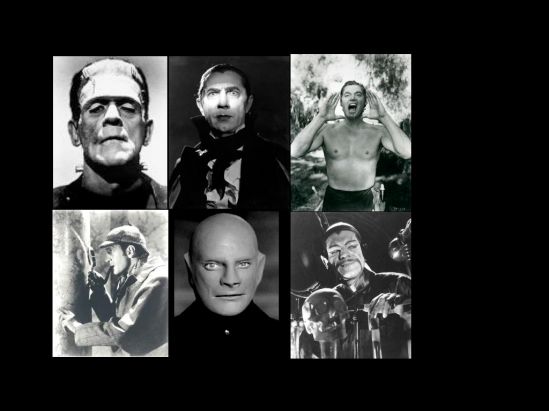

In this talk we will be looking at the medial logics and serial dynamics of iconic popular figures, taking Dracula as a paradigmatic example of a “spectral” logic that enables serial figures to proliferate across medial channels. By “serial figure,” we mean a type of stock character populating the popular-cultural imagination of modernity; a “flat” and recurring figure, subject to one or more media changes over the course of its career. We see serial figures as integral and ideologically powerful components of the political and economic order of modernity, which works expansively to increase commensurability and connectivity. Serial figures operate in this system as mediating instances between the familiar and the unknown, the ordinary and the unusual. It is thus not by accident that such figures are characteristically liminal, transitional, or border-crossing beings – straddling the divide between nature and technology like Frankenstein’s monster, between life and death like Dracula, human and animal like Tarzan, or oscillating between moral and ethnic positions like Sherlock Holmes, Fantômas, or Fu Manchu. These figures parasitically appropriate the media ensembles of a given period, taking up residence in them and making them their own; at the same time, serial figures are in a way themselves media of modernization, higher-order media that gather together and focus attention on media undergoing change. This is especially true with regard to the cultural and commercial logic of the “update,” according to which transformations and transitions in the modern media landscape are negotiated and sold as “innovations.” But characterized as they are by a reversible relation to media as both instrument and environment – as both (diegetic) object of interest and as the very horizon of perception, expression, or narration – serial figures lend themselves also to a retrospective view of media change as non-teleological, overdetermined by competing forces and yet haunted by a spirit of indeterminacy and a sense that “things could have been otherwise.”

In the following, we will first try to flesh out this picture and explain more precisely what a serial figure is, what it does, and how it operates. Our focus will be on the figure of Dracula, who perhaps more than any other serial figure brings into focus what we’re designating the “spectral” logic of serial proliferation: that is, a ghostly and flickering relation to presence, or the present, which characterizes the medial historicity of the serial figure and propels its ongoing transformations as it moves between old and new media – from text, to film, to radio, TV, and toward the digital. Seen in this light, it is the spectrality of the figure, the fact that it’s neither (completely) here nor there, that keeps the figure alive – or, more precisely, undead – never quite exhausted by a single, definitive instantiation but always at least potentially available for yet another serial iteration.

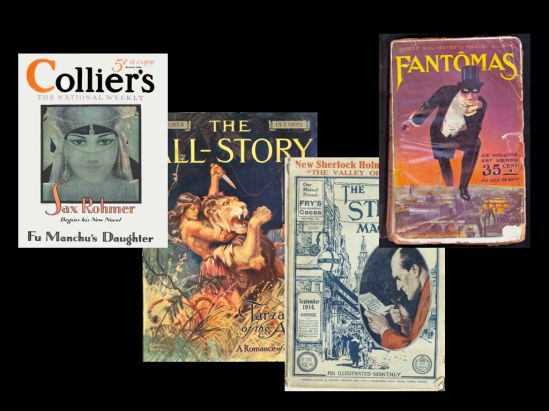

2. Serial Framings & the Spectral Integrity of the Icon

A serial figure is a figure that needs no explanation, no introduction, and no elaborate framing – it is familiar, even if one has never dealt explicitly with the figure. The serial figure is distinguished here from the series character, which is developed in an ongoing narrative (for example, a soap opera, a serial novel, or a saga). Serial figures – as Umberto Eco once wrote of Superman – undergo a “virtual beginning” with each new staging, “ignoring where the preceding event left off.” Series characters grow and develop a more or less linear biography, while serial figures are characterized by repetitions, revisions, and even the occasional “reboot” of their entire history. Serial figures and series characters must, however, be understood as ideal-typical figurations; often, they blend into one another in the course of their narrative unfolding. Indeed, serial figures quite often derive from series characters: many (like Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Fu Manchu, Fantômas) were first introduced in the continuing narratives of serialized magazine productions, then further developed in novel series, before eventually mutating into serial figures proper as they jumped across various medial channels (Denson/Mayer 2012a/b).

Serial figures have an extreme affinity to modern media, and they seem positively to thrive on media changes. Though many classical serial figures were established in literary texts, they all jumped very quickly to other media, mutated, fanned out, proliferated, and reproduced without losing their distinctive forms, features, trademark equipment or gear. As a result, they are particularly good at introducing the cultural or medial “new,” and thus at mediating novelty against the background of a figure’s familiarity – serial figures both foreground or exoticize and familiarize the foreign or unknown. This marking and familiarization is achieved not only narratively, but also formally – by way of serial iteration. Serial figures are not developed linearly from A to B; rather, their careers unfold along branching paths, across nodes, loops, and resonances, by way of a “concrescent” or compounding, sedimenting rather than sequential form of seriality.

Even before the comics superheroes of the 1930s took up and adapted many of their characteristics, serial figures presented themselves as both long-familiar and strangely new, at once timeless and hypermodern, universal and particular alike. For a long time, however, the serial figures of the turn of the century have been read almost exclusively in terms of the atavistic, the primitive, the unconscious – in any case, not the modern. This approach culminated in the 1960s in the reception history of Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism. For Dracula, Frye’s impact registers in the assumption of a “majestic immutability” informing the representation of the vampire through the ages, as Nina Auerbach delineated in her cultural history of the vampire (1995: 130; cf. Douglas 1966). This assumption then gave way, in the wake of intellectual history and Foucault’s “archaeology of knowledge,” to a more historically and medially specific approach, as exemplified by Nina Auerbach’s own take on vampires as “personifications of their age” (3): instead of transhistorical continuities, scholarship now foregrounded historical breaks and radical revisions.

But cultural contextualization alone is not enough to get a handle on the cultural careers of serial figures. We have to pay attention both to their iconicity and variability, and towards this end we have to focus on the serial figure’s mediality – or, more generally: its formal framing. To understand the constructive force of such framing, one should not stretch the frame too far. If you look not at Tarzan, but at primate-human hybrids in the history of Western culture, not at Dracula but the vampire from Byron to True Blood, not Frankenstein’s monster but man-machine configurations since the early modern era – you run the risk of overlooking the specific medial dynamics of popular seriality, a dynamics of modern and hence mass and technical media. Connected to the inherent reproducibility of modern media, this properly serial dynamic draws on an awareness of something being re-told, activating a dialectics of recognition and astonishment, of departures from and re-anchorings of previously staged narratives and images. The more concrete the anchor points and cross-references in a serial sequence, the more clearly does this logic manifest itself. And only with regard to this logic can we recognize the political-ideological and medial-material “work” of the serial figure, its anchoring in a specific world-historical era.

Dracula himself is very much a product of the late colonial era, and the threat he poses is accordingly “dynamic, totalizing.” Earlier monsters operated “on the margins of society, hidden away in their towers,” while modern creatures of horror are figures of expansion and spread. “The modern monsters,” writes Franco Moretti with a view particularly toward Dracula, “threaten to live for ever and to conquer the world. For this reason they must be killed” (Moretti 1982: 68). Dracula, not the generic vampire, comes from Transylvania, and thus from the border region between East and West; a region which does not yet demarcate horror and superstition at the time of the figure’s inception but “the vexed ‘Eastern Question’ that so obsessed British foreign policy in the 1880s and 90s” (Arata 1990: 627; see also Richards 1993: 56-64; Gibson 2006). In our minds, Dracula always has pointed teeth, he always wears a cape, always sleeps in a coffin, and he concentrates on female victims, even if he got along during various stretches of his serial career without some of these habits and accoutrements. In its iconicity, the figure of Dracula mobilizes a whole army of basic conceptual oppositions, pitting them against one other, but without the prospect of resolution: East meets West, the predator threatens civilized humanity, masculine agency preys on the female victim – and, of course, life and death entwine in the vampire’s uncanny body. None of these pairs of terms remains unproblematic or stable in the course of the figure’s long career, but all of them reappear again and again in various guises and constellations. In his serial specificity, Dracula thus stands out among vampires – he no longer embodies the sensibility of the early Victorian period, nor yet has he assumed that of our late televisual postmodernity. There is a diffuse – indeed spectral – integrity to the figure across its various medial instantiations; its iconic appearance will always by superimposed upon any and all possible concrete manifestations, even if (and perhaps especially if) the figure now appears in a different form.

3. Dracula’s Medial Dialectics

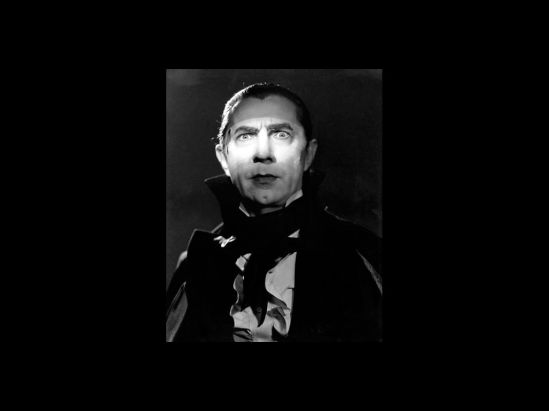

The figure’s iconic form has been fixed for us above all by Bela Lugosi’s portrayal of the Count in Tod Browning’s 1931 film version, to which we will return shortly, but first we turn briefly to Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel from which the figure first sprang to … uhh … “life.” The source text helps us to see the presence of a further conceptual pair at work in the serial unfolding of the figure: for the novel is marked, in a way that problematically straddles its diegetic “inside” and its medial “exterior,” by an unsettled tension between the diversification of media and an effort to commensurabilize or contain them. This tension is energized by the spirit of a transitional phase in which the medium of the novel – still the master medium of entertainment in the late Victorian era – starts to cede its territory to the technical mass media that shaped entertainment in the twentieth century. As we shall see, the unresolved tension between the specificity and generality of mediation is also generative of the sights and sounds of Count Dracula as he proliferates serially across the century’s audiovisual channels.

More than perhaps any other serial figure, Dracula reveals the active and creative power of technical media already at his literary point of departure. In Thomas Elsaesser’s estimation, which follows Friedrich Kittler’s seminal reading in Aufschreibesysteme, “[Dracula] may be the only original and authentic myth that the age of mechanical reproduction has produced” (2011: 111). Kittler read Dracula as “that perennially misjudged heroic epic of the final victory of technological media over the blood-sucking despots of old Europe” (Kittler, 1999: 86). And Kittler was not the only critic to read the novel as the document of a media struggle, in which an alliance built on modern media of communication is pitted against an ancient and totalitarian power (see also Wicke 1992; Richards 1993). While we very much agree that Dracula should be read as a novel about mediatization and media change, however, we are not so sure about its actual position within this battle – its sympathies, as it were. Technical media may prove superior in the battle of forces that the novel both depicts and takes part in. But the alliances or opposing camps within this battle are far less clear-cut than one might think. This may have to do with the fact that the triumph of the technical media of entertainment was about to deal a fatal blow to the very medium of the novel. The very particular novel at hand, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, does not openly militate against the media system of the twentieth century, we argue. But it is by no means as celebratory of its own format’s impending replacement as is often assumed.

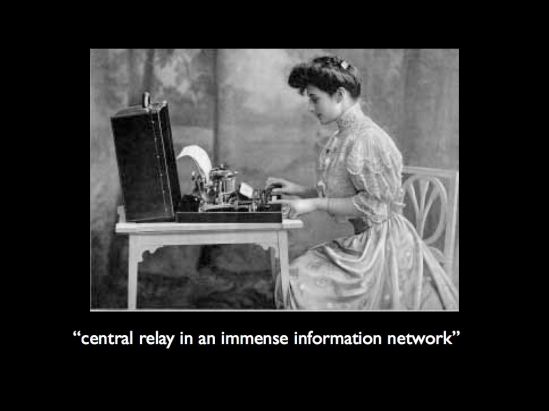

In line with this reconsideration of alliances and tensions, we contend that Dracula serves not so much as an outdated antecedent to the mass-media cultures of modernity, but as an integral element – perhaps even a basic principle – of them. Already at the point of his literary inception, Dracula embodies a principle of diffusion, of intermedial spectrality, according to which one material form is translatable into another: the humanoid, the wolf, bat, and fog. This allows him for a time to elude his pursuers, but they too are acquainted with a plurality of media forms: shorthand notation, the telegraph, the phonograph, and the typewriter play instrumental roles in this counter-project. Mina Harker, as Dracula’s most important opponent and the driving engine of the international alliance of vampire hunters in the metropolis, is a skilled typist, and she manages to render the fractured records of journals, newspapers, phonograph cylinders, and stenographic notes into the uniform medium of typewritten text, reproduced in triplicate; Mina becomes what Kittler called the “central relay in an immense information network” (Discourse Networks 354). In doing so, however, Mina also cleanses the new technological media of communication of their ‘rawness’ and authenticity: “I have copied out the words on my typewriter, and none other need to now hear your heart beat, as I did” (199), she reassures Dr. Seward after having reviewed his phonograph cylinders. Simultaneously, and interestingly, she defuses what could be considered the most powerful forcefield of the late Victorian novel, obliterating the traces of feeling, the trembling and the terror, the horrible events’ profound impact on the ‘soul.’ At the very end of the novel, her husband, Jonathan Harker, summarizes in frustration that “in all the mass of material of which the record is composed, there is hardly one authentic document; nothing but a mass of type-writing […]. We could hardly ask anyone, even did we wish to, to accept these as proofs of so wild a story” (335).

Fortunately, the version of the events that the book ultimately renders is not Mina’s purified, streamlined, typewritten collection of data, but Bram Stoker’s lurid and sprawling ‘imperial gothic’ (Brantlinger 1995). With this, the novel counters the “modern” ideal of totalizing data processing with another, older, aesthetics of totality – collating voices, perspectives, and media in order to achieve an impression of synchronicity and homogeneity. Dracula thus displays its tacit predilection for the media system of the nineteenth century and its unacknowledged skepticism vis-à-vis the technical media of the upcoming age. But the novel is fighting a losing battle on behalf of its own format. At the novel’s end, Dracula will be defeated while Mina has just given birth to a son, who shall bear all the first names of the league of vampire hunters. But, alas, in the story’s longer run, the powers of reproduction are afforded to the vampire rather than the Victorian lady. What distinguishes Mina in the novel – her interiority, her reflection, her robust presence – disqualifies her for a serial career and confines her to the bounds of the book. Dracula, in contrast, who is hardly ever ‘there’ in the novel, transgresses its boundaries and lives on, by virtue of his capacity to defer closure and synchronicity.

Rooted diegetically in the serial infection process by which the curse of the undead spreads, Dracula’s power far exceeds the text’s limits, formally and materially resisting the closure of the work. Dracula taunts his pursuers: “My revenge is just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side. Your girls that you all love are mine already; and through them you and others shall yet be mine […]” (273). In his flickering dispersion he seems to project various options for a future vampiric existence, tentatively envisioning nodes and links to future versions of himself. In that respect, the novel functions – against its own best interest and almost as if being operated by an alien force – as the ideal starting point for the figure’s serial proliferation.

Dracula’s spectral quality resides in his uncanny ability to navigate not only (diegetic) time and space but also to spread diffusely through the very real experiential timespaces that rub against one another in modernity, in the oppositional trajectories of medial particularization and convergent totalization. Transcending the novel – which is itself a site of convergent mediality wherein distinctions are effaced in the effort to correlate, coordinate, and ultimately thus to entomb the shape-shifting villain – Dracula emerges as a higher-order medium, thus acting simultaneously as a parasitic harbinger and a host of media transformation. The meta-medium of the serial figure accentuates the insufficient totality or completeness of the book as compared to audiovisual media – the media of silent and sound film, radio, and television into which the Count will successively and temporarily descend, before he inevitably pulls up stakes (so to speak) and moves on. In this interplay of first-order and second-order media, or between medial specificity and comparability, the sights and sounds of Dracula become the sights and sounds of media change itself.

4. The Icon as Transitional Medium

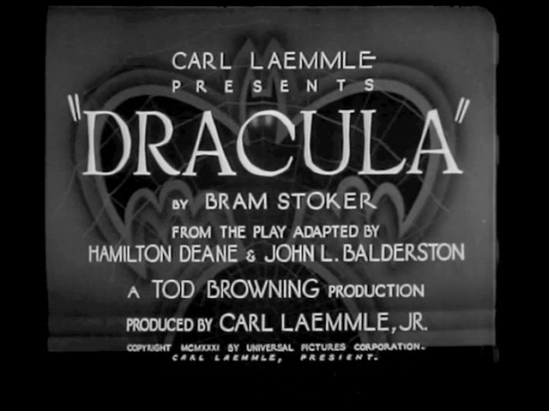

The transitional interplay of medial figure and ground is nowhere so tightly focused as in Tod Browning’s classic film from 1931 – particularly in the iconic image it bequeaths to us of Count Dracula. The film’s title card already evidences the plurimedial seriality that the figure had amassed over the previous three decades: “Carl Laemmle presents Dracula by Bram Stoker” – not as a direct adaptation of the novel, but “from the play adapted by Hamilton Deane & John L. Balderston,” which in fact refers to two plays: first a London-based production from 1924 and then a 1927 Broadway play based on it, and starring Bela Lugosi. Not mentioned here are Stoker’s own theatrical production, performed only once (prior to the novel’s publication) for the purpose of securing a copyright, Friedrich Murnau’s unauthorized adaptation Nosferatu from 1922, or any of the print editions, adaptations, abridgments, and serializations that had appeared since 1897. But what’s about to appear on screen will in any case overshadow all of those past interpretations, including the original novel, and it will continue to color our perception of any future instantiation for decades to come. Significantly, Browning’s film kicks off the horror-film cycle of the 1930s, including a series of Universal Studios productions featuring the Count: after Dracula (1931) comes Dracula’s Daughter (1936), then Son of Dracula (1943), the monster mash-ups House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), and finally Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), in which Lugosi reprises his role one last time. The figure, like the horror film, changes markedly over the course of this series, though, so it’s easy to lose sight of the originary medial functionality of Lugosi’s icon, which is born in the wake of the transition from silent to sound film. By film historian Donald Crafton’s reckoning, this transition was coming to its end by the time Dracula appeared in February 1931, but as Robert Spadoni has argued, the film harnessed a lingering experience of the first sounds moviegoers had heard emitted from the screen – an uncanny or “ghostly” experience resulting from the incomplete phenomenal coordination of sound and image. The Count gave a body to this recently bygone (but unforgotten, “undead”) experience, around which the horror genre itself was initially fashioned.

In this context, Browning’s film re-enacts the novel’s battle between medial particularization and generalization – abstracting it, though, from Mina’s and Stoker’s divergent efforts to coordinate medial fragments into a coherent textual whole, and transferring it to a probing of the cinema’s recent efforts to coordinate sight and sound into a coherent audiovisual whole. Dracula’s body is the central site of the struggle, the medial stakes of which are made clear in the film’s first ten minutes or so, leading up to the Count’s appearance and first encounter with his guest. The non-diegetic music with which the film opens will cease after the opening credits, and it will not reappear again until the closing credits. But the opening scene, set inside a noisy horse-drawn coach traveling through Transylvania, locates us more or less unproblematically in the sound-era of cinema, as onscreen characters converse and produce audible dialogue. Soon, though, as we move deeper into the wilds of Transylvania, this will stop and give way to an eerie silence. When the sun sets and our traveler Renfield (here playing the role of the novel’s Harker) sets out for Borgo Pass, a series of images show the Count’s distant castle, first from the outside, then its interior, bringing us swiftly to his coffin. There is no sound at all, until the interminable silence is broken by the sound of coffins opening, creaking, bumping, then rats squeaking, wolves barking, howling, as the camera moves in to reveal Dracula, who has silently appeared. The background of silence contrasts palpably with the use of non-diegetic music during the credits. This might be called a non-diegetic silence, as it foregrounds the images as silent, setting the stage for an uncanny sound, very different from the normalized sound of dialogue that precedes it. The silence has, of course, a diegetic aspect, but it is also double in a way, standing out as the spectral presence of a material and medial absence. (By way of contrast, a “regular” (diegetic) silence might conventionally be marked with the sound of crickets chirping.) Renfield’s carriage arriving now at Borgo Pass brings with it – and takes with it again just as quickly – the normalized (i.e. synchronized) sound we saw in the opening sequences, again foregrounding the uncanny silence of Dracula, who awaits Renfield ominously in his own carriage. Renfield’s somewhat fearful words to the silent count – “The coach from Count Dracula?” – seem awkwardly obtrusive against the background of silence, and the aural register itself alternates as ground and figure with the image of the tight-lipped count. Visually, Dracula’s bulging eyes accentuate this interplay, as they themselves describe a partially autonomous figure against the ground of his face – thereby singling out vision and visuality and setting them in a volatile and oscillating relation with sound and the sonic, before the Count’s coach heads off with its passenger toward the castle.

Along the way, Renfield discovers that a bat has silently replaced the driver, and upon arrival he confirms that the driver is missing, while the castle door creaks open – autonomously and ostentatiously. Renfield enters, bats squeak, armadillos rustle. Dracula descends the staircase silently behind the frightened Renfield’s back. “I am Dracula.” Renfield explains hastily he thought he was in the wrong place. Awkwardly, Dracula replies, “I bid you welcome.” Wolves howl in the background. “Listen to them! Children of the night. What music they make.” This self-reflexive foregrounding of sound, captured for the purposes of the uncanny, reimagines the Jazz Singer’s famous “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” It will reverberate again in Tarzan’s yell, and – somewhat paradoxically – also in the muteness of Frankenstein’s monster, all of which stand in a self-reflexive relation to the sound-film transition.

The interplay of silence/sound, noise/speech, visual/sonic continues in London: there we hear the noisy metropolis, the scream of a first offscreen victim, and the music of the opera house, all of which are contrasted with the silence of the house at night, where a bat waits noiselessly at the window, enters without a sound, and where an offscreen transformation allows Dracula to appear just as noiselessly at Lucy’s bedside. This is followed by the screams of the madhouse and its raving lunatics, including Renfield, contrasted with the concentrated silence of Seward and the other doctors, and of van Helsing before he announces that they’re dealing with the undead, Nosferatu. Dracula communicates with Renfield without speech, seemingly with his eyes – which, in the iconic image, are highlighted with precise rays of light, producing an effect much like the bulging eyes earlier, again making vision/the visual the carrier of (a weird, for us indecipherable sort of) information, while sound is alienated from the image and rendered as incomprehensible noise – thus “denaturing” the recently naturalized, modern system of communication via synchronized sound and vision. It is significant that sound is produced, if not as dialogue, only by objects and nonhuman animals, never by the count’s body in humanoid form, which is perfectly and uncannily silent both in motion and at rest. Later, the count’s invisibility in the cigar-case mirror, first noticed by van Helsing, further problematizes sound/image relations, as Dracula is audible while not (mediately) visible. The fact that he “casts no reflection in the mirror” in fact mirrors or translates the fact that his body also emits no sound. Thus, sound and vision are dissociated from one another, both of them operating as channels of significance and its deformation in a joint effort to undo the habitualization of synchronized sound and reveal an experience of disjointedness and material excess at its base. This excess, this spectral materiality, refuses to be contained completely by the new medium of sound film. The latter is shown to be “haunted” by a stubborn spirit of medial transitionality, embodied by Dracula, which resists containment in a neat medial package just as the Count could not be contained in the novel.

The film reinstates, in this way, the excess that Mina, in the novel, had erased in her transcription of Seward’s cylinders. But it does so in a way that sits uneasily with Stoker’s own attempt to restore a novelistic “spirit” to his apparently dying medium. For the film transfers the mechanism of phonography, the technical capture of the aural real, from the level of content to that of the medium, which it self-reflexively foregrounds; accordingly, the material excess of breath (literally, “spirit”) and heartbeat that Mina erased from the cylinders are restored and channeled towards the nervous, embodied reactions of the spectator confronted with the early horror film.

As in the novel, then, but for very different purposes, Dracula again thrives on, marks, and carries forth an unsettling spirit of medial transitionality: whereas Stoker sought to counter the impending changes to the media landscape of the nineteenth century, Browning allows the figure to extend the scope of the cinema’s sound transition – and with it the vampire’s own power. Problematizing the coordination of sound and image, Dracula’s uncanny image continually reinstates the distinction between sonic and visual registers, thus thwarting the medial coherence of the talkie, obstructing the normalization of a generalized audiovisual mediality. Rather than be contained by the medium of the sound film, Dracula himself becomes the medium in which the particular streams of sound and image can appear, juxtaposed and disjoined, forever at battle. Browning’s film thus continues the trajectory of serialization that the Count embarked upon when he escaped and transcended Mina’s and Stoker’s textualizing efforts in 1897. And though the medial self-reflexivity of the icon will fade from view as the sound transition recedes further into the past and the figure further establishes its place in popular culture, it is the icon’s spectral instrumentalization of the unsettled relations between medial particularity and generality that in part ensures its ongoing serial power.

Imagining Media Change — Photos from the Symposium

Here are some images from our symposium “Imagining Media Change,” which took place on June 13, 2013:

Above, Ruth Mayer opening the symposium with some nice words of welcome.

Jussi Parikka talking about “Cultural Techniques of Cognitive Capitalism: On Change and Recurrence” in his wonderful opening keynote.

Jussi Parikka talking about “Cultural Techniques of Cognitive Capitalism: On Change and Recurrence” in his wonderful opening keynote.

Florian Groß delivering his talk “The Only Constant is Change: American Television and Media Change Revisited” — with examples from Mad Men.

Florian Groß delivering his talk “The Only Constant is Change: American Television and Media Change Revisited” — with examples from Mad Men.

Bettina Soller on hypertext and fanfic in her talk “How We Imagined Electronic Literature and Who Died: Looking at Fan Fiction to See What Became of the Future of Writing”.

Bettina Soller on hypertext and fanfic in her talk “How We Imagined Electronic Literature and Who Died: Looking at Fan Fiction to See What Became of the Future of Writing”.

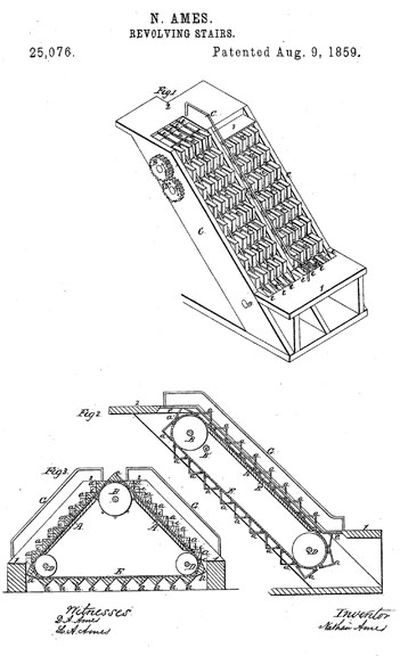

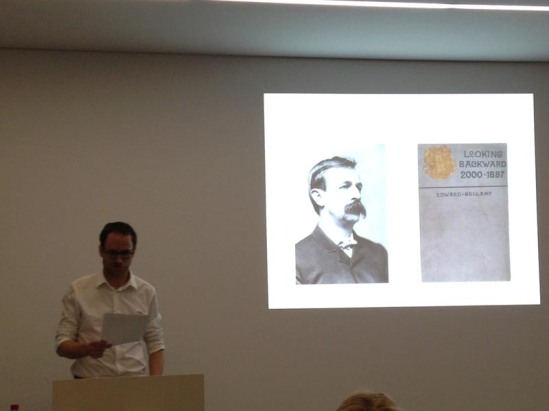

Me, Shane Denson, on escalators and “On NOT Imagining Media Change”.

Me, Shane Denson, on escalators and “On NOT Imagining Media Change”.

Wanda Strauven delivering the second keynote, “Pretend (&) Play: Children as Media Archaeologists” — a lively talk with great examples!

Wanda Strauven delivering the second keynote, “Pretend (&) Play: Children as Media Archaeologists” — a lively talk with great examples!

Christina Meyer talking about the Yellow Kid and “Technology – Economy – Mediality: Nineteenth Century American Newspaper Comics”.

Christina Meyer talking about the Yellow Kid and “Technology – Economy – Mediality: Nineteenth Century American Newspaper Comics”.

Ilka Brasch talking about early film serials and “Facilitating Media Change: The Operational Aesthetic as a Receptive Mode”.

Ilka Brasch talking about early film serials and “Facilitating Media Change: The Operational Aesthetic as a Receptive Mode”.

Alexander Starre wrapping up the symposium with an excellent talk on “Evolving Technologies, Enduring Media: Material Irony in Octave Uzanne’s ‘The End of Books’”.

Alexander Starre wrapping up the symposium with an excellent talk on “Evolving Technologies, Enduring Media: Material Irony in Octave Uzanne’s ‘The End of Books’”.

And finally, here are a few more random pictures:

Shane Denson, “On NOT Imagining Media Change”

Abstract for Shane Denson’s talk at the symposium “Imagining Media Change” (June 13, 2013, Leibniz Universität Hannover):

On NOT Imagining Media Change

Shane Denson

There are many ways in which we imagine media change and technological transformation; foremost among them, in the modern era, are popular and commercial visions of the future – from science-fiction narratives to advertisements for the latest gadget guaranteed to change your life. However, if we suppose that human agencies are inextricably tied to, and in part enabled by, the material infrastructure of a media-technological environment, then our imaginations – as they are focused, reflected, or courted in representational media – must be seen to lag behind infrastructural shifts, which would sweep our imagining subjectivities along with them. If, that is, our capacity to imagine media change is itself mediated through a changing media-technological environment, then certain aspects of media change must be categorically immune to imagination.

In this presentation, I will focus on this phenomenon of NOT imagining media change. I will outline a theoretical model according to which media change pertains not only to empirically determinate transformations in media-technical apparatuses and systems, but more broadly to the environmental substrate of discursive and phenomenological subjectivities. I will argue that a pre-reflective “anthropotechnical interface,” based in proprioceptive and visceral sensibilities, constitutes the primary site of media change. Accordingly, the embodied parameters of our imaginative faculties are themselves subject to radical transformation, such that both spectacular and unobtrusive changes in the media environment can occasion deep changes in our experiential frameworks – changes that elude representation and imagination.