Back in June, I posted a screencast video of “Frame, Sequence, Medium: Comics in Plurimedial and Transnational Perspective,” a presentation I gave at the German Association for American Studies 2011 annual conference in Regensburg. This got me thinking about making screencast versions of other talks I’ve given. Here is one for a talk entitled “Media Crisis, Serial Chains, and the Mediation of Change: Frankenstein on Film,” which I gave at the American Studies Association annual conference in San Antonio, Texas on November 19, 2010.

Shaviro’s Response

Following the great round of presentations and lively discussions, Steven Shaviro has now offered his concluding response, wrapping up the theme week on his book Post-Cinematic Affect at In Media Res. In related news, over at his blog The Pinocchio Theory, he’s also posted a text on “post-continuity,” framed by a response to Mattias Stork’s video essay “Chaos Cinema.” There’s still lots to think about here, and I’m sure the discussion is not over yet…

More Post-Cinematic Moments

Following Elena del Rio’s post on “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect” (to which I responded here), the theme week at in media res on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has continued with two great presentations: Paul Bowman’s “Post-Cinematic Effects” and now Adrian Ivakhiv’s “A Hair of the Dog that Bit Us.” Bowman’s presentation is framed by a clip from Old Boy, while Ivakhiv uses Grace Jones’s video “Corporate Cannibal.” Both of these, like del Rio’s presentation on Monday, raise some crucial questions for understanding our contemporary media moment. If you haven’t been following the presentations and discussions, check it out now. Following Patricia MacCormack’s presentation tomorrow, Steven Shaviro is scheduled to respond to all of these takes (and tangents) on his work on Friday.

Metabolic Images and Post-Cinematic Affect

Over at in media res, the theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has gotten underway with an intriguing post by Elena del Rio from the University of Alberta entitled “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect,” which I highly recommend reading/viewing. I wanted to post a short response there, but for some reason I am unable to log in to do so. So I’m posting my response here for the time being, but will post again at in media res when possible.

Over at in media res, the theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has gotten underway with an intriguing post by Elena del Rio from the University of Alberta entitled “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect,” which I highly recommend reading/viewing. I wanted to post a short response there, but for some reason I am unable to log in to do so. So I’m posting my response here for the time being, but will post again at in media res when possible.

(Note that the following draws on ideas that I develop at much greater length in Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, which I am currently revising for publication, and attempts to set them in relation to del Rio’s response to Shaviro’s notion of post-cinematic affect.)

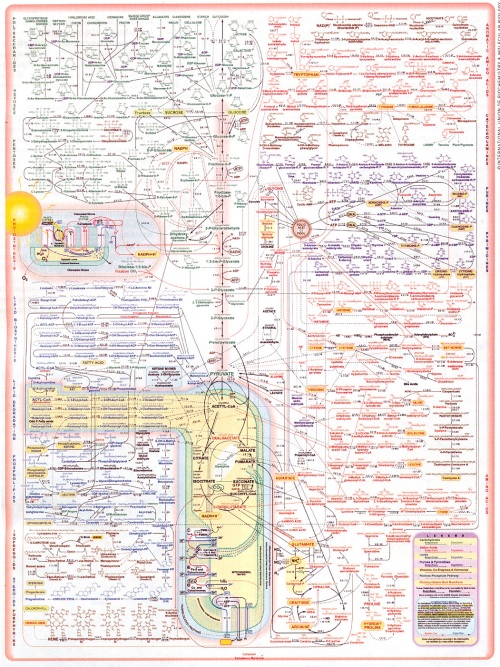

What Deleuze calls the “vital power that cannot be confined within species [or] environment” (quoted by Elena del Rio in her post at in media res) might profitably be thought in terms of “metabolism”—a process that is neither in my subjective control nor even confined to my body (as object) but which articulates organism and environment together from the perspective of a pre-individuated agency. Metabolism is affect without feeling or emotion—affect as the transformative power of “passion” that, as Brian Massumi reminds us, Spinoza identifies as that unknown power of embodiment that is neither wholly active nor wholly passive. Metabolic processes are the zero degree of transformative agency, at once intimately familiar and terrifyingly alien, conjoining inside/outside, me/not-me, life/death, old/novel, as the power of transitionality—marking not only biological processes but also global changes that encompass life and its environment. Mark Hansen usefully defines “medium” as “environment for life”; accordingly, metabolism is as much a process of media transformation as it is a process of bodily change. The shift from a cinematic to a post-cinematic environment is, as del Rio describes it, a metabolic process through and through: “Like an expired body that blends with the dirt to form new molecules and living organisms, the body of cinema continues to blend with other image/sound technologies in processes of composition/decomposition that breed images with new speeds and new distributions of intensities.” To the extent that metabolism is, as I claimed, inherently affective (“passionate,” in a Spinozan vein), del Rio is right that post-cinematic affect has to be thought apart from feeling, certainly apart from subjective emotion. Del Rio’s alternative approach, which (in accordance with Deleuze’s mode of questioning while thinking beyond the time-image) asks about the image, taking it as the starting point of inquiry, is helpful. The challenge, though, becomes one of grasping the image itself not as an objective entity or process but as a metabolic agency, one which is caught up in and defines the larger process of transformation that (dis)articulates subjects and objects, spectators and images, life and its environment in the transition to the post-cinematic. This metabolic image, I suggest, is the very image of change, and it speaks to a perspective that is the perspective of metabolism itself—an affect that is distributed across bodies and environments as the medium of transitionality. As del Rio rightly suggests, exhaustion—mental, physical, systemic—is not at odds with affect; rethinking affect as metabolism (or vice versa) might help explain why: exhaustion, from an ecological perspective, is itself an important, enabling moment in the processes of metabolic becoming.

Post-Cinematic Affect: Theme Week at In Media Res

This notice serves to advertise both a “medium” and its “message” (which, according to McLuhan is always another medium–and this is certainly true in this case). If you don’t already know the website In Media Res (the “medium” in question), you should definitely take a look. It’s an innovative and exciting project that works like this: each week, a group of people deal with a given media-related topic or theme (the “message,” so to speak) through the mixed media of a short video clip (30 sec. to 3 minutes in most cases) and a short textual accompaniment (between 300 and 350 words)–the medium’s message, itself media-oriented, is very literally composed of other media.

Now, the message has arrived that next week, the topic of discussion will be Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect, about which I recently posted. I quote here from Adrian Ivakhiv’s blog immanence:

Next week, the Media Commons project In Media Res will be hosting a theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect (which I wrote about here).

I’ll be guest curating the discussion on Wednesday, and Steven will be responding on Friday.

Here’s the full line up:

- Monday August 29: Elena Del Rio (University of Alberta, Canada)

- Tuesday August 30: Paul Bowman (Cardiff University, UK)

- Wednesday August 31: Adrian Ivakhiv (University of Vermont, USA)

- Thursday September 1: Patricia MacCormack (Anglia Ruskin University, UK)

- Friday September 2: Steven Shaviro (Wayne State University, USA)

To participate you will need to take a moment to register here.

This promises to be an exciting event, and it should be especially interesting to members of the Film & TV Reading Group. Mark your calendars!

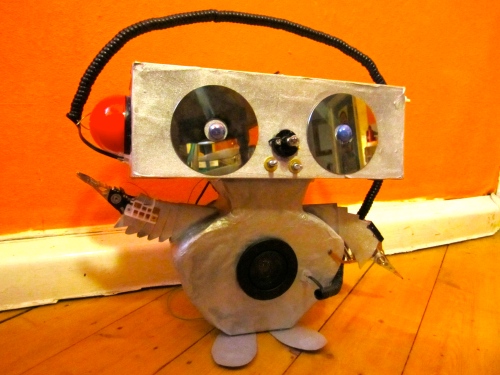

Media Art: Robotic Remediations

Real, working (self-built!) radio in retro-future robot look; mixed media: radio, dismantled hard drive, old-school telephone cable, papier-maché, cardboard, glass beads, hot glue, working light bulb and socket, 2 x AA batteries, Pokéball, silver spray paint.

Artist: Ari Denson (my 9-year-old son!)

UPDATE: Ari and his robot appeared in the newspaper (Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung) last week:

The newspaper article is online here.

Multistable Frames

Stephanie Hoppeler, Lukas Etter, and Gabriele Rippl (whose research project “Seriality and Intermediality in Graphic Novels” is associated with the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality–Aesthetics and Praxis”) have put together a workshop titled “Interdisciplinary Methodology: The Case of Comics Studies,” which will take place on October 14-15, 2011 in Bern. In the organizers’ own words:

“Our motivation for this event is to reduce what we see as a stark discrepancy between the popularity of Comics Studies on the one hand and the virtual lack of encompassing methodological reflection on the other.

We have planned one keynote speech for each of the two days: Dr. Thierry Groensteeen (freelance lecturer and curator; founder of www.citebd.org) will hold an introductory speech on Friday 14 October, and Dr. Roger Sabin (lecturer at Central St. Martins University of the Arts, London) will give a paper on Saturday 15 October. Each speech shall be followed by several thematic panels, in which researchers will present their papers and thereby introduce a broader discussion.

[Papers have been chosen that] include or stimulate reflection on the methodological issues Comics Studies and Intermediality Studies raise, as well as on possibilities to tackle these issues.”

One of those papers will be presented by yours truly. The paper develops the phenomenological approach to comics that was implicit in my paper at the DGfA conference this year in Regensburg, “Frame, Sequence, Medium: Comics in Plurimedial and Transnational Perspective” (screencast video here, in case you missed it). In particular, my talk in Bern will expand on the notion of the “multistable frame,” which I introduced as a way of talking about comics and their emergent serialities in the earlier paper. Here is the abstract for my presentation in Bern:

Multistable Frames: Notes Towards a (Post-)Phenomenological Approach to Comics

Shane Denson

“In the available accounts of the theories and methods of popular culture studies, phenomenology is conspicuously absent” (Carroll, Tafoya, and Nagel 1)—thus observe the editors of a volume meant to rectify that situation, published in the year 2000. But over a decade later their statement remains largely true. In the meantime, popular culture itself has changed, as have the studies devoted to it: new theories and methods have emerged, and different phenomena have come into view. Developments in and around comics and graphic novels are exemplary: comics themselves have been transformed through contact with digital media, their social status revised largely through the graphic novel, and they have come to exert an unprecedented influence on mainstream cinema and television. Today, comics cannot be ignored, neither in the broad field of popular culture nor in the more specialized realms of academic study: increasingly, comics are being researched with a great variety of methods by literary scholars, historians of art and culture, media theorists, and even philosophers. Looking back from this vantage point, we may find the absence of phenomenology among fin-de-millennium approaches to popular culture less surprising than the conspicuous absence of comics in a volume dedicated to Phenomenological Approaches to Popular Culture. Phenomenology and comics, or so it would seem, pass like ships in the night—and this despite the fact that the insights of some of the seminal works on comics, such as Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art and Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, were arrived at through methods and means of looking at comics that were implicitly phenomenological in nature. It remains, then, to make these methods explicit, and to transform phenomenological insights into a genuine methodology available for the study of comics. As a first step towards this goal, I propose rethinking Eisner’s and McCloud’s classic contributions through the lens of categories and concepts developed by American philosopher Don Ihde for the phenomenological study of “mediating technologies.” Adapted to the medium of comics, and applied specifically to the central figure of the frame that, in various forms (e.g. panels, speech balloons, pages as meta-panels), dominates Eisner’s and McCloud’s analyses of comics as a sequential art, Ihde’s phenomenological categories lend greater depth to our understanding of comics as an experiential domain, throwing phenomena like the achievement of “closure” (as McCloud puts it) between panels into sharper relief, but at the same time revealing the requisite negotiations between and amongst frames and the internal and external spaces they define as a highly complex process. The apparently simple act of reading comics, that is, is revealed as a highly complex process, one involving a non-linear dynamics that can be traced back to the recursive nestings and reversibilities of frames as phenomenal objects. Ultimately, the multistability of comics’ framings, as revealed in a phenomenological analysis, points towards the logic of flickering oscillations that Derrida has exposed under the rubric of the parergon, and hence to a postphenomenological approach that destabilizes any categorical difference between subjects (or readers) and objects (or comics). Nevertheless, a phenomenological methodology may prove to be the only route to understanding the irreducible experiential entanglements involved in our transactions with comics as a medium of the multistable frame.

Carroll, Michael T., Eddie Tafoya, and Chris Nagel. “Introduction: Being and Being Entertained: Phenomenology and the Study of Popular Culture.” Phenomenological Approaches to Popular Culture. Eds. Michael T. Carroll and Eddie Tafoya. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 2000. 1-18.

Derrida, Jacques. The Truth in Painting. Trans. by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1987.

Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art. Rev. ed. New York: Norton, 2008.

Ihde, Don. Technics and Praxis. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1979.

_____. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1990.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1993.

Just for fun: Kubrick / Scorsese mash-up

Dylan Trigg’s uncanny (film) phenomenology

Just a few days ago, I linked to Adrian Ivakhiv’s article “The Anthrobiogeomorphic Machine: Stalking the Zone of Cinema” in the most recent issue of Film-Philosophy. Another highlight in that issue comes from Dylan Trigg, a researcher at the Centre de Recherche en Epistémologie Appliquée in Paris, whose blog Side Effects I just recently discovered. Trigg’s paper, “The Return of the New Flesh: Body Memory in David Cronenberg and Merleau-Ponty,” can be found here; and here is the abstract:

Just a few days ago, I linked to Adrian Ivakhiv’s article “The Anthrobiogeomorphic Machine: Stalking the Zone of Cinema” in the most recent issue of Film-Philosophy. Another highlight in that issue comes from Dylan Trigg, a researcher at the Centre de Recherche en Epistémologie Appliquée in Paris, whose blog Side Effects I just recently discovered. Trigg’s paper, “The Return of the New Flesh: Body Memory in David Cronenberg and Merleau-Ponty,” can be found here; and here is the abstract:

From the “psychoplasmic” offspring in The Brood (1979) to the tattooed encodings in Eastern Promises (2007), David Cronenberg presents a compelling vision of embodiment, which challenges traditional accounts of personal identity and obliges us to ask how human beings persist through different times, places, and bodily states while retaining their sameness. Traditionally, the response to this question has emphasised the importance of cognitive memory in securing the continuity of consciousness. But what has been underplayed in this debate is the question of how the body can both reinforce and disrupt the grounds for our personal identity. Accordingly, by turning the notoriously “body conscious” work of Cronenberg, especially his seminal The Fly (1986), I intend to pursue the relation between identity and embodiment in the following way.

First, by augmenting John Locke’s account of personal identity with a specific appeal to the body, I will explore how Cronenberg’s treatment of embodiment as a site of independent experience challenges the idea we have that cognitive memory is the guarantor of personal identity. Cronenberg’s treatment of the “New Flesh” posits an account of the body that undermines the Cartesian and Lockean account of personal identity as being centred on the mind. In its place, I will argue that Cronenberg shows us how the body establishes a personality independently of the mind.

Second, through focusing explicitly on body memory, I will explore how we, as embodied subjects, relate to our bodies in a Cronenbergian world. Approaching this relation between memory and embodiment via the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty, I will argue that memory is at the heart of Cronenberg’s vision of body horror. I will conclude by suggesting that far from generating unity, Cronenberg’s vision of embodiment and identity is diseased (often literally) by a memory that cannot be assimilated by cognition. The result of this failure to assimilate body memory, is that memory itself occupies the role of the monster within.

As evidenced on his blog, Trigg is doing some really fascinating phenomenological work (for example, a great post here on “The Language of Hauntings”), and his book, The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny, is due out in 2012 (available now for pre-order). Here’s the publisher’s blurb for the book:

From the frozen landscapes of the Antarctic to the haunted houses of childhood, the memory of places we experience is fundamental to a sense of self. Drawing on influences as diverse as Merleau-Ponty, Freud, and J. G. Ballard, The Memory of Place charts the memorial landscape that is written into the body and its experience of the world.

Dylan Trigg’s The Memory of Place offers a lively and original intervention into contemporary debates within “place studies,” an interdisciplinary field at the intersection of philosophy, geography, architecture, urban design, and environmental studies. Through a series of provocative investigations, Trigg analyzes monuments in the representation of public memory; “transitional” contexts, such as airports and highway rest stops; and the “ruins” of both memory and place in sites such as Auschwitz. While developing these original analyses, Trigg engages in thoughtful and innovative ways with the philosophical and literary tradition, from Gaston Bachelard to Pierre Nora, H. P. Lovecraft to Martin Heidegger. Breathing a strange new life into phenomenology, The Memory of Place argues that the eerie disquiet of the uncanny is at the core of the remembering body, and thus of ourselves. The result is a compelling and novel rethinking of memory and place that should spark new conversations across the field of place studies.

Edward S. Casey, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Stony Brook University and widely recognized as the leading scholar on phenomenology of place, calls The Memory of Place “genuinely unique and a signal addition to phenomenological literature. It fills a significant gap, and it does so with eloquence and force.” He predicts that Trigg’s book will be “immediately recognized as a major original work in phenomenology.”

I highly recommend checking out Dylan Trigg’s blog and his article in Film-Philosophy, and I look forward to reading his wonderful-sounding book!

Adrian Ivakhiv’s ecocritical film-philosophy

Adrian Ivakhiv, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Vermont, maintains the excellent blog immanence, where he posts regularly on “the Form, Flesh, and Flow of the World : Ecoculture, Geophilosophy, Mediapolitics” (as he puts it in the blog’s byline).

Adrian Ivakhiv, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Vermont, maintains the excellent blog immanence, where he posts regularly on “the Form, Flesh, and Flow of the World : Ecoculture, Geophilosophy, Mediapolitics” (as he puts it in the blog’s byline).

Recently, he linked to a new article of his in the open-access online journal Film-Philosophy (published by the great Open Humanities Press), in a special issue on “Phenomenology and Psychoanalysis.” Here is the abstract of Ivakhiv’s paper, which is certainly worth reading in full:

The Anthrobiogeomorphic Machine: Stalking the Zone of Cinema

This article proposes an ecophilosophy of the cinema. It builds on Martin Heidegger’s articulation of art as ‘world-disclosing,’ and on a Whiteheadian and Deleuzian understanding of the universe as a lively and eventful place in which subjects and objects are persistently coming into being, jointly constituted in the process of their becoming. Accordingly, it proposes that cinema be considered a machine that produces or discloses worlds. These worlds are, at once, anthropomorphic, geomorphic, and biomorphic, with each of these registers mapping onto the ‘three ecologies,’ in Felix Guattari’s terms, that make up the relational ontology of the world: the social, the material, and the mental or perceptual. Through an analysis of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), I suggest that cinema ‘stalks’ the world, and that our appreciation of its potentials should similarly involve a kind of ‘stalking’ of its effects in the material, social, and perceptual dimensions of the world from which cinema emerges and to which it returns.

Keywords:

Film theory; film-worlds; ecocriticism; ecologies; Tarkovsky

Beyond this paper, Ivakhiv is working on a book called Ecologies of the Moving Image, which I very much anticipate reading. Indeed, in many respects, Ivakhiv seems a kindred spirit of sorts in his process-relational philosophical orientation and his endeavor to formulate a non-anthropocentric philosophy of film. With his notion that the cinema is one of the places “in which subjects and objects are persistently coming into being, jointly constituted in the process of their becoming,” Ivakhiv’s views seem largely apposite with my own film-theoretical project, which, as I summarized (in German) recently, seeks a “rapprochement between the conflicting human and nonhuman agencies inhabiting [Frankenstein] films” and the cinema in general. As I outline it in Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, this “rapprochement […] consists […] of a recognition of the mutual articulation of experience by human and nonhuman technical agencies, whereby the affective and embodied experience of anthropotechnical transitionality is not arrested and subjugated to human dominance, but approached experimentally as a joint production of our postnatural future” (24). Ivakhiv’s proposal “that cinema be considered a machine that produces or discloses worlds” seems, in my opinion, to point in the same – experimental and postphenomenological – direction.