Flyer for my “Frankenstein and Film” class, Spring 2017 at Stanford. Complete syllabus here.

Flyer for my “Frankenstein and Film” class, Spring 2017 at Stanford. Complete syllabus here.

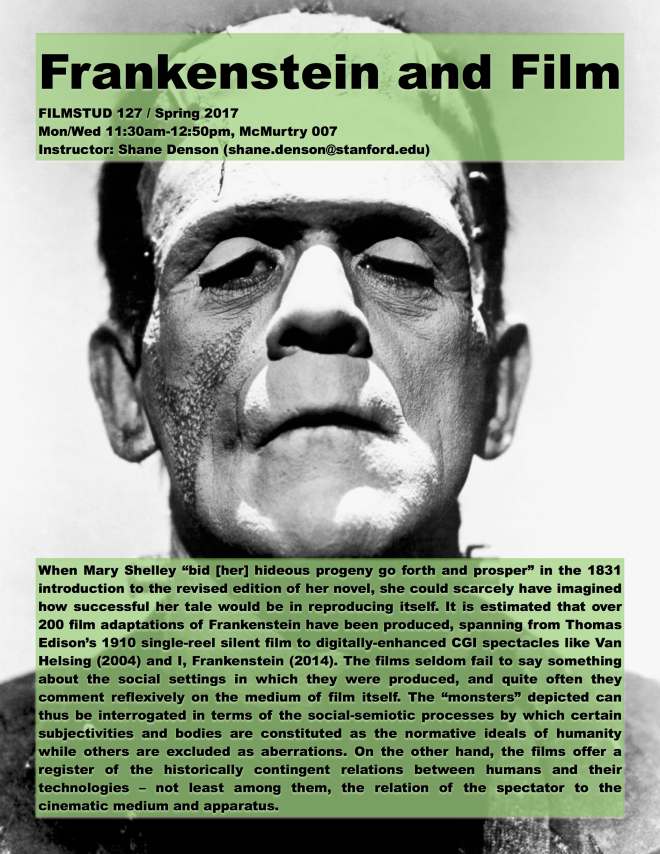

The latest issue of MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen/Reviews includes a nice review of my book Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface.

For those of you who read German, you can find the entire text of the review, by Anya Heise-von der Lippe (Tübingen/Berlin), here. For everyone else, here is a (rough) translation of the reviewer’s summary statement:

“Postnaturalism offers a philosophical approach and an engagement with fundamental ontological and phenomenological questions of human and nonhuman materiality, which is indispensable especially for a post-postmodernity characterized by resource scarcity, climate change, and species extinctions, as well as the threat of a return to essentialist positions in politics and popular culture. Adapting a phrase from Bruno Latour, Denson counters the latter with a postnatural position: “We have never been natural” (24). Furthermore, Denson’s detailed examination — at the level of content, reception, and production — of Frankenstein adaptations is an asset for the analytical and production-aesthetic [produktionsästhetische] investigation of a central text (or modern myth) and its many adaptations in a wide range of text-critical disciplines: from media studies to literary to cultural studies.”

(Again, the translation is rough. Tweaks are more than welcome! Especially if you have suggestions for produktionsästhetisch or for making that first sentence more readable, drop me a line in the comments below…)

Finally, make sure you check out the entire issue of MEDIENwissenschaft, which is chock full of great stuff. Of particular interest to readers of this blog, among other things: the “Perspectives” section contains a longer piece on seriality and television series’ interrelations by Tanja Weber and Christian Junklewitz.

Check out the full contents of the issue here.

The latest issue of Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, a special (English-language) issue on Serial Narratives edited by Kathleen Loock (a fellow member of the DFG research unit on “Popular Seriality”), includes a review of my book Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface.

The latest issue of Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, a special (English-language) issue on Serial Narratives edited by Kathleen Loock (a fellow member of the DFG research unit on “Popular Seriality”), includes a review of my book Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface.

The review, by Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich of the University of Kiel, is mostly positive, though hardly uncritical. You can read the entire review here, but my favorite part must be a certain characterization of the book that appears in the midst of exposing what Büscher-Ulbrich takes as “the book’s theoretical Achilles’ heel” (namely, my lack of engagement with overtly political revolutions and with “recent post-Marxist political ontologies and metaphysics” in particular). In this context, Büscher-Ulbrich nonetheless flatteringly praises my “extraordinary powers of theoretical synthesis” and claims that

“[Postnaturalism] is one of the rare enough scholarly monographs whose collected footnotes alone provide an excellent education.”

Now, I recognize that it’s not for everyone (I have been criticized before for including “an entire second essay within an essay”) — and while I’m not sure I’d recommend taking your kids out of school and making Postnaturalism the primary textbook for their homeschooling (though you might do worse…) — I’m glad to see the footnotes getting some attention here from a reader who can appreciate the value of a page of text “below the line.”

In any case, if Postnaturalism ever sees a second edition, I’ll certainly suggest this as a fitting blurb!

Check out the entire review:

And check out the entire special issue of LWU on Serial Narratives!

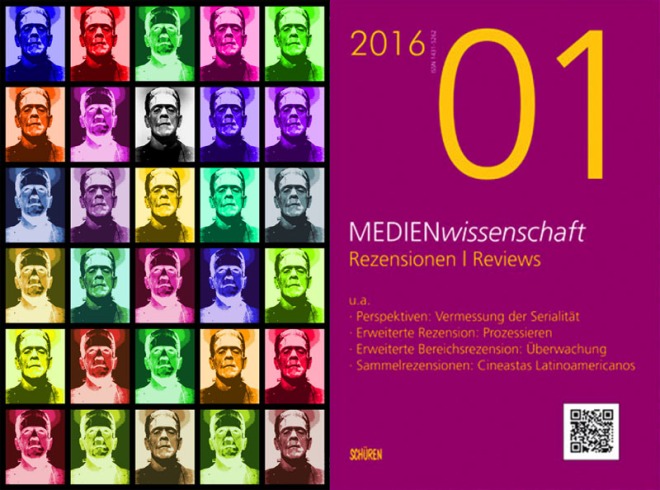

Some time ago, I posted that my book Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface had officially been made available by Columbia University Press, which serves as distributor in North and South America and Australasia. Shortly thereafter, massive restructuring of the CUP website led to the book’s temporary disappearance, but it is now back up here, and it has just appeared in CUP’s Spring 2015 Catalog (pictured above) as well.

If you’d like to preview the book, the best places to look are either at the Transcript-Verlag website (here; click “Excerpt” or “PDF” below the cover image) or the Google Books preview for the book (here).

Finally, it’s worth noting that you can get the book much cheaper than its official $60 price tag if you look for it on amazon or other outlets.

My book Postnaturalism has been out since July, but there was a slight delay with US distribution. Now, however, the book is officially available for order through Columbia University Press.

This is probably more important for university libraries, who might want to order directly from CUP (if your library doesn’t have a copy yet and you’re in any position to do so, please do consider requesting they order one). For everyone else, you can currently get a copy much cheaper through marketplace sellers on amazon.com (right now, around $38 for a new copy, rather than the $60 list price at CUP).

Finally, a preview of the book has gone up at Google Books. Check it out here.

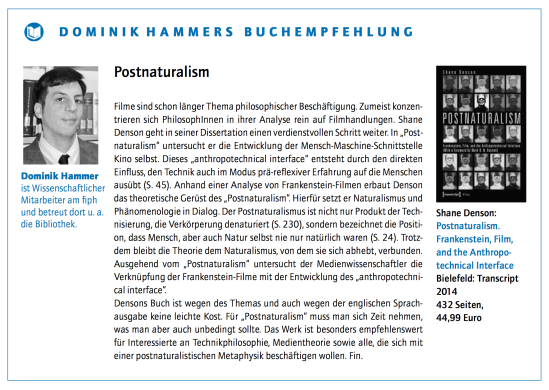

A short review of my book Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface has just appeared in fiph journal 24 (October 2014) — the journal of the Forschungsinstitut für Philosophie Hannover (the Research Institute for Philosophy Hannover, or “fiph” for short). The review, in German, was written by Dominik Hammer of the fiph, and it includes a brief summary and a nice endorsement of the book, part of which I translate here for those who don’t read German:

Postnaturalism is not only the product of a technicization that denatures embodiment (p. 230); rather, it designates the position that the human, but also nature itself, was never natural (p. 24). Nevertheless, the theory remains beholden to the naturalism from which it takes off and sets itself apart [sich abhebt]. Setting out from this “postnaturalism,” the media theorist investigates the connection between Frankenstein films and the development of the “anthropotechnical interface.”

Denson’s book […] is no light fare. For Postnaturalism you have to take your time, but it’s definitely worth it. The work is especially to be recommended for those interested in the philosophy of technology, media theory, and anyone who wants to engage with a postnaturalistic metaphysics.

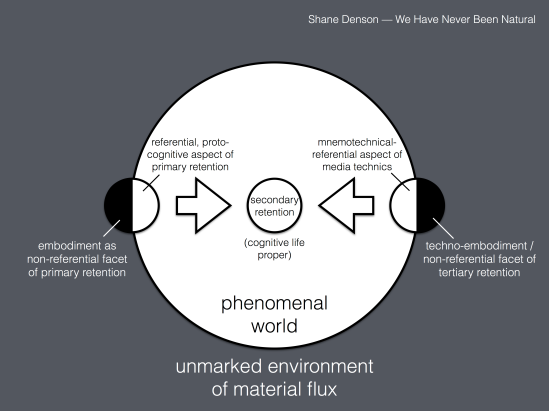

Both aesthetically and conceptually, the diagram above is imperfect in many ways. It is, necessarily, an oversimplification; I hope that it might nevertheless serve a positive purpose by giving visible form to an otherwise somewhat abstract argument. Developed for my talk at the upcoming “Philosophy After Nature” conference in Utrecht (you can find my abstract here), the diagram could also serve as an emblem for the argument I make in Chapter 6 of Postnaturalism. In that chapter, I look at (among other things) Mark Hansen’s concept of “the medium as an environment for life” (as introduced in his paper “Media Theory,” which appeared in Theory, Culture & Society); this concept, developed in conversation with Bernard Stiegler’s philosophy of technics, has been very important for my work, and grappling with it was central for me in the process of arguing that “we have never been natural.”

In the course of developing his concept, Hansen argues that there is an asymmetrical priority of human embodiment in the transductive relation between technics and the human. In Hansen’s engagement with Stiegler, this prerogative of embodiment is seen to be at odds, to a certain extent, with Stiegler’s argument about the synchronization or industrialization of experience through the action of recording technologies. The latter embody “tertiary retentions” of experience, beyond the primary and secondary retentions that Husserl theorized as the operations, respectively, of immediate temporal experience and of recollection or memory. According to Stiegler, in a complex argument that I will not try to summarize here, tertiary retention (technical recording) injects secondary retention (memory) into primary retention (the immediate experience of the “adherent present,” from which flows also the future) — effectively instituting a pre-formatted future on a mass scale (especially in the age of live television and real-time media).

Following an objection raised by Jean-Michel Salanskis, who sees a paradox or split in Husserl’s notion of primary retention — a split between the referential aspect that aligns primary retention with conscious experience, on the one hand, and a non-referential aspect that is wholly unconscious, on the other — Hansen argues that Stiegler’s argument diminishes the robust role of embodiment in the production of temporal experience. The synchronization envisioned by Stiegler is dependent, according to Hansen, on a bracketing of embodied agency; the “mnemotechnical constitution of time” prioritized by Stiegler is thus secondary to the “corporo-technical constitution of time” that Hansen identifies as an infra-empirical condition of experience. Hence the asymmetrical privileging of human embodiment in the medial transduction of human and technical agencies.

The diagram above summarizes my own intervention in the context of these debates. Rather than reinstituting the priority of the human within the anthropotechnical transduction, my suggestion is that we conceive tertiary retention (and media technics more generally) as similarly split between a referential (“mnemotechnical” or broadly representational) and a non-referential (materially embodied) aspect. With memory flanked on both sides by a non-discrete, smooth space of matter, cognitive life is then situated squarely in a realm staked out between robustly material agencies—between the subpersonal operation of the body, on the one hand, and the subphenomenal, infra-empirical material agency of technics on the other. As the diagram tries to indicate, a certain symmetry is restored in the anthropotechnical interface, which on this model describes the joint production of empirical reality — the distributed (human and nonhuman) agency by which the phenomenal realm is demarcated from out of the unmarked environment of material flux.

As I wrote here recently, I will be taking part in a roundtable discussion on media theory at this year’s FLOW Conference at the University of Texas (September 11-13, 2014). My panel — which will take place on Friday, September 12 at 1:45-3:00 pm (the full conference schedule is now online here) — consists of Drew Ayers (Northeastern University), Hunter Hargraves (Brown University), Philip Scepanski (Vassar College), Ted Friedman (Georgia State University), and myself.

In preparation for the panel, which is organized as a roundtable discussion rather than a series of paper presentations, each of us is asked to formulate a short position paper outlining our answer to an overarching discussion question. Clearly, the positions put forward in such papers are not intended to be definitive answers but provocations for further discussion. Below, I am posting my position paper, and I would be happy to receive any feedback on it that readers of the blog might care to offer.

Nonhuman Media Theories and their Human Relevance

Response to the FLOW 2014 roundtable discussion question “Theory: How Can Media Studies Make ‘The T Word’ More User-Friendly?”

Shane Denson (Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany / Duke University)

1. Theory Between the Human and the Nonhuman

Rejecting the excesses of deconstructive “high theory,” approaches like cultural studies promised to be more down-to-earth and “user-friendly.” While hardly non-theoretical, this was “theory with a human face”; against poststructuralism’s anti-humanistic tendencies, human interaction (direct or mediated) returned to the center of inquiry. Today, however, we are faced with (medial) realities that exceed or bypass human perspectives and interests: from the microtemporal scale of computation to the global scale of climate change, our world challenges us to think beyond the human and embrace the nonhuman as an irreducible element in our experience and agency. Without returning to the old high theory, it therefore behooves us to reconcile the human and the nonhuman. Actor-network theory, affect theory, media archaeology, “German media theory,” and ecological media theory all highlight the role of the nonhuman, while their political (and hence human) relevance asserts itself in the face of very palpable crises – e.g. ecological disaster, which makes our own extinction thinkable (and generates a great variety of media activity), but also the inhuman scale and scope of global surveillance apparatuses.

2. With Friends Like These…

The roundtable discussion question asks how theory can be made more “user-friendly”; but first we should ask what this term suggests for the study of media. Significantly, the term “user-friendly” itself originates in the context of media – specifically computer systems, interfaces, and software – as late as the 1970s or early 1980s. Its appearance in that context can be seen as a response to the rapidly increasing complexity of a type of media – digital computational media – that function algorithmically rather than indexically, in a register that, unlike cinema and other analogue media, is not tuned to the sense-ratios of human perception but is designed precisely to outstrip human faculties in terms of speed and efficiency. The idea of user-friendliness implies a layer of easy, ergonomic interface that would tame these burgeoning powers and put them in the user’s control, hence empowering rather than overwhelming. As consumers, we expect our media technologies to empower us thus: they should enable rather than obstruct our purposes. But should we expect this as students of media? Should we not instead question the ideology of transparency, and the disciplining of agency it involves? Hackers have long complained about the excesses of “user-obsequious” interfaces, about “menuitis” and the paradoxical disempowerment of users through the narrow bandwidth interfaces of WIMP systems (so-called because of their reliance on “windows, icons, menus/mice, pointers”). Such criticisms challenge us to rethink our role as users – both of media and of media theory – and to adopt a more experimental attitude towards media, which are capable of shaping as much as accommodating human interests.

3. Media as Mediators

The give and take between empowerment and disempowerment highlights the situational, relational, and ultimately transformational power of media. And while cultural studies countenanced such phenomena in terms of hegemony, subversion, and resistance, the very agency of the would-be “user” of media might be open to more radical destabilization – particularly against the background of media’s digital revision, which “discorrelates” media contents (images, sounds, etc.) from human perception and calls into question the validity of a stable human perspective. More generally, it makes sense to think about media in terms of agencies and affordances rather than mere channels between pre-existing subjects and objects – to see media, in Bruno Latour’s terms, not as mere “intermediaries” but as “mediators” that generate specific, historically contingent differences between subject and object, nature and culture, human and nonhuman. Recognizing this non-neutral, lively and unpredictable, dimension of media invites an experimental attitude that not only taps creative uses of contemporary media (as in media art) but also privileges a sort of hacktivist approach to media history as non-linear, non-teleological, and non-deterministic (as in media archaeology) – and that ultimately rethinks what media are.

4. Speculative Media Theory

By expanding the notion of mediation beyond the field of discrete media apparatuses, and beyond their communicative and representational functions, approaches like Latour’s actor-network theory gesture towards a nonhuman and ultimately speculative media theory concerned with an alterior realm, beyond the phenomenology of the human (as we know it). This sort of theory accords with the aims of speculative realism, a loose philosophical orientation defined primarily by its insistence on the need to break with “correlationism,” or the anthropocentric idea according to which being (or reality) is necessarily correlated with the categories of human thought, perception, and signification. Contemporary media in particular – including the machinic automatisms of facial recognition, acoustic fingerprinting, geotracking, and related systems, as well as the aesthetic deformations of what Steven Shaviro describes as “post-cinematic” moving images – similarly problematize the correlation of media with the forms (and norms) of human perception. More generally, a speculative and non-anthropocentric perspective equips us to think about the way in which media have always served not as neutral tools but, as Mark B. N. Hansen argues, as the very “environment for life” itself.

5. Media Theory for the End of the World

Perhaps most concretely, the appeal of this perspective lies in its appropriateness to an age of heightened awareness of ecological fragility. As we begin reimagining our era under the heading of the Anthropocene – as an age in which the large-scale environmental effects of human intervention are appallingly evident but in which the extinction of the human becomes thinkable as something more than a science-fiction fantasy – our media are caught up in a myriad of relations to the nonhuman world: they mediate between representational, metabolic, geological, and philosophical dimensions of an “environment for life” undergoing life-threatening climate change. Like never before, students of media are called upon to correlate content-level messages (such as representations of extinction events) with the material infrastructures of media (like their environmental situation and impact). The Anthropocene, in short, not only elicits but demands a nonhuman media theory.

My new book, Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, has been out for about a month now — in Germany, at least. The American, British, French, and Japanese iterations of amazon list the book as appearing next week, on August 22 (but available for pre-order), and it may be September by the time the American distributor, Columbia University Press, gets it listed on their website. Meanwhile, living somewhere between these worlds, I was able to get my hands on a physical copy of the book yesterday, and I’m very happy with the job Transcript Verlag did!

For more information about the book, as well as a preview that includes Mark Hansen’s foreword and my introduction, see here or click the image above (the preview can be accessed by clicking “PDF,” just beneath the cover image, on the publisher’s page). Also, if you are in any position to do so, please consider requesting a copy for your university library.

Thanks to everyone who helped me get this out there! And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper. I have an affection for it, for it is the offspring of happy days…

Readers of the blog will recognize this post’s title — “We have never been natural” — as the nutshell slogan for postnaturalism, as it is developed in my forthcoming book of the same title. Now that slogan is also the title of a talk I will be giving at the 2014 Society for European Philosophy and Forum for European Philosophy joint annual conference, “Philosophy After Nature,” which will take place September 3-5, 2014 in Utrecht, Netherlands.

In the talk, I try to get to the media-philosophical heart of postnaturalism and develop the core argument to the extent possible in a 20-minute presentation. Here is the abstract:

We Have Never Been Natural: Towards a Postnatural Philosophy of Media

Shane Denson (Leibniz Universität Hannover / Duke University)

In this presentation, I draw upon concepts and arguments put forward by Bernard Stiegler, Mark B. N. Hansen, Niklas Luhmann, and Bruno Latour and put them into conversation with one another in order to develop what I term a postnatural philosophy of media. Postnaturalism, as I define the term, does not signal the end of nature but a particular manner of rethinking it. Methodologically, postnaturalism marks an extension of rather than a break with (scientific and epistemological) naturalism and its insistence on material evolution as the basis of consciousness and all ideational, symbolic, or discursive realities. Substantively, however, this extension implies a rethinking of nature because technical agencies are seen as not only immanent to the natural but also crucially implicated in the transformative force of evolution. Accordingly, postnaturalism implies that “we have never been natural” (and neither has nature, for that matter). At the heart of this rethinking is what I call the “anthropotechnical interface”: a sub-phenomenal, infra-empirical stratum of materiality, which forms the site of radical transformation by means of the “unnatural selection” that results from the technical mediation of embodied life. This view, which can be developed with the help of Bernard Stiegler’s philosophy of technology, implies a special role for media; accordingly, as I argue, media serve as nothing less than the “originary correlators” of the phenomenal and the noumenal.

My argument for this (seemingly extravagant) claim involves an adaptation of Niklas Luhmann’s systems-theoretical conception of mediality, which (when subjected to a transformative rethinking that abstracts media beyond the system-immanent position to which they are relegated in Luhmann’s thought) provides a formal model for thinking media as the site of sub-phenomenological changes taking place at the very cusp between systemic enclosure and the unmarked environment from which any and all systems emerge. Expanding on Mark B. N. Hansen’s notion of media as the “environment for life” itself, my argument goes on to question the cognitive or mnemotechnical bias of Stiegler’s philosophy of technology while also reversing Hansen’s asymmetrical privileging of human embodiment in the transductive relation between organic and inorganic agencies. Ultimately, the postnatural philosophy of media that results from these encounters works to articulate together process-oriented and object-oriented perspectives; besides (and beyond) empirically determinate manifestations in the form of discrete apparatic entities, media play a wholly non-anthropic role in the production of the empirical, in the constitution and maintenance of its spatio-temporal foundations. As a matter of “distributed embodiment,” media play a literally central role in the transduction of materially intersecting entities, each with their own form of embodiment, their own manner of marking the boundary, embodying the membrane, between material flux and the emergent realm of discrete objects.

Bibliography:

Denson, Shane. Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface. With a foreword by Mark B. N. Hansen. Bielefeld: Transcript, forthcoming 2014.

Hansen, Mark. Embodying Technesis: Technology Beyond Writing. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2000.

_____. “Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 23.2-3 (2006): 297-306.

_____. New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

_____. “‘Realtime Synthesis’ and the Différance of the Body: Technocultural Studies in the Wake of Deconstruction.” Culture Machine 6 (2004). <http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/9/8>.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993.

Luhmann, Niklas. Art as a Social System. Trans. Eva M. Knodt. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000.

_____. Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1997.

_____. Social Systems. Trans. John Bednarz, Jr., with Dirk Baecker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995.

Stiegler, Bernard. Technics and Time 1: The Fault of Epimetheus. Trans. Richard Beardsworth and George Collins. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998.

_____. Technics and Time 2: Disorientation. Trans. Stephen Barker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2009.

_____. Technics and Time 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise. Trans. Stephen Barker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2011.