The following is the text of my short presentation on “Frankenstein, Film, and Chemistry,” which I delivered on October 18, 2019 at the “Chemistry and Film: Experiments in Living” joint symposium of the Stanford Departments of Chemistry and of Art & Art History.

“Frankenstein, Film, and Chemistry”

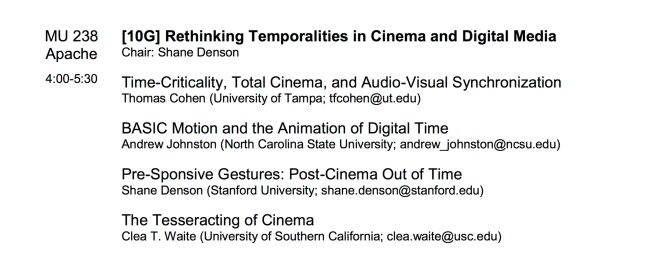

Shane Denson

It has been estimated, perhaps with a bit of exaggeration, that there are over 200 cinematic adaptations of Frankenstein. These films are sometimes more, sometimes less true to the letter and the spirit of Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel, but they are all, in the words of today’s symposium title, what might be called “experiments in living”—aesthetic, narrative, and technological experiments in giving, shaping, and controlling life.

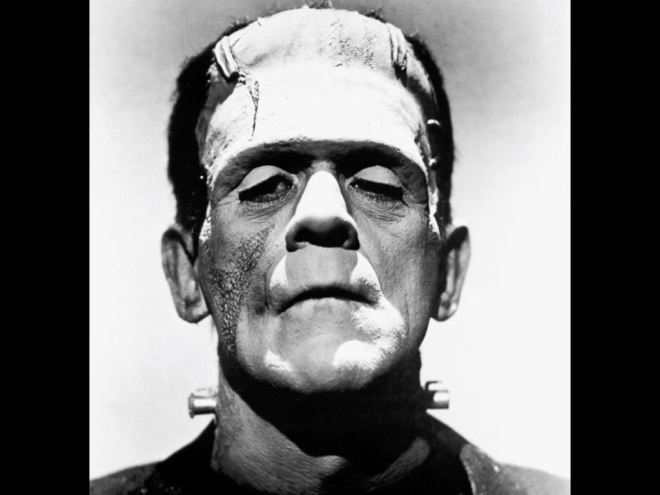

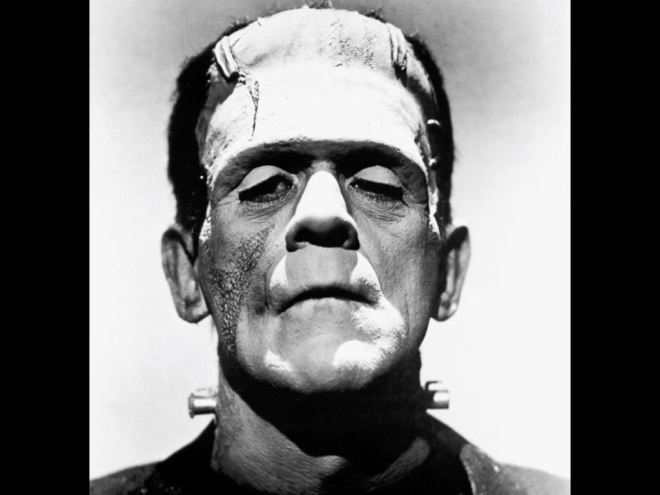

The most iconic versions of the tale (such as James Whale’s 1931 film starring Boris Karloff as the flat-headed monster with electrodes in his neck) generally frame these efforts as studies in electrical engineering rather than applied chemistry.

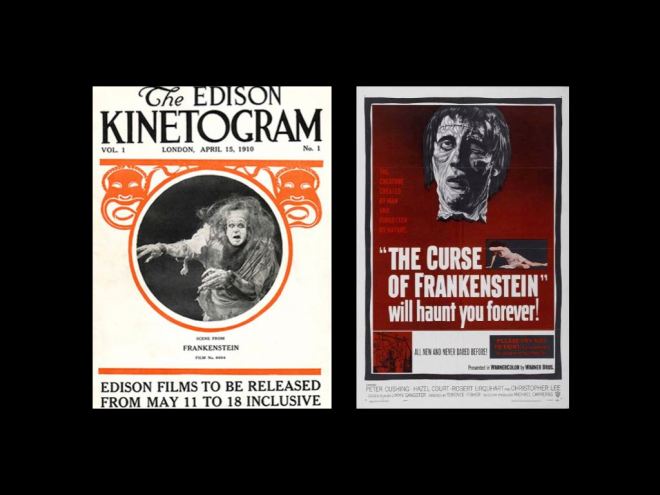

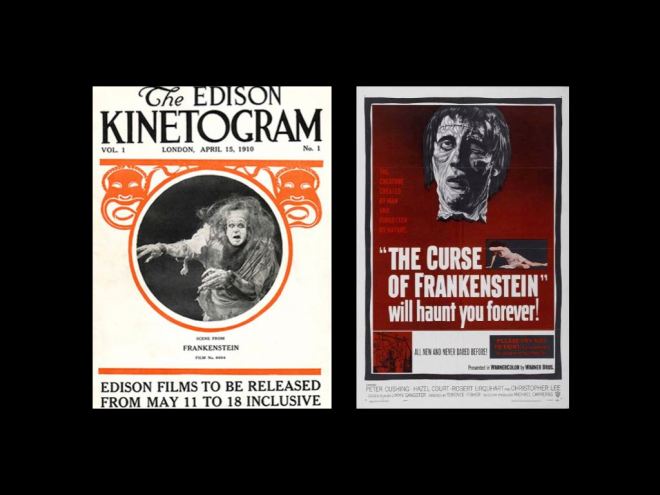

However, a minor strand of Frankenstein films, including Thomas Edison’s 1910 film and Hammer Studios’ 1957 Curse of Frankenstein, attend also to chemistry—picking up on Victor Frankenstein’s keen interest in alchemy, as suggested in Shelley’s novel, and focusing it towards the cinematic medium’s own photochemical processes. In this way, narrative and medial chemistries mix in self-reflexive spectacles that foreground the material processes of giving life to, or “animating,” moving images as much as the monsters they depict.

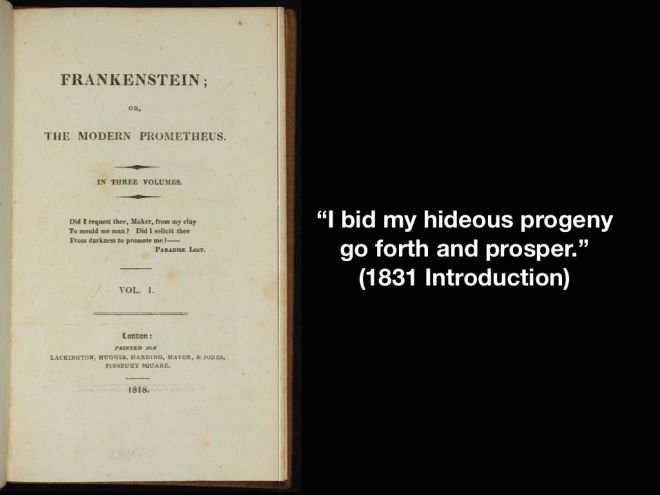

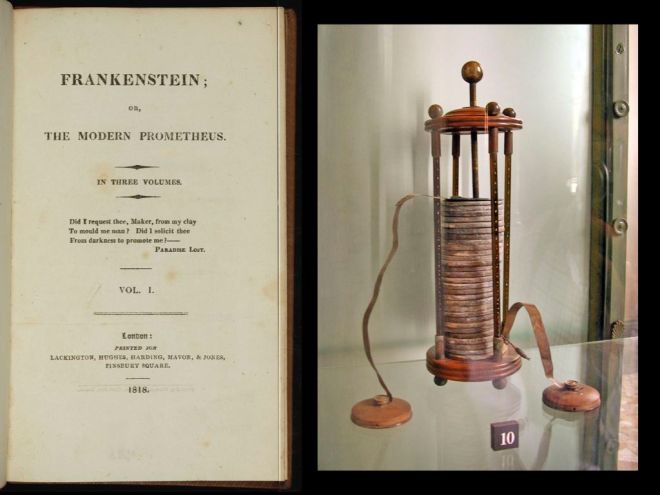

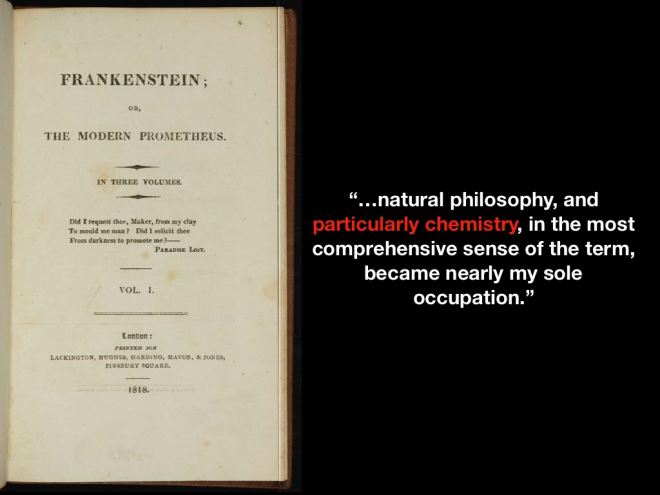

Both the self-reflexive impulse of these films and their focus on chemistry have their roots in Mary Shelley’s novel, first published in 1818. Most famously, with respect to self-reflexivity, Shelley established a relation between literary authorship and the book’s monstrous act of creation when, in the Introduction to the 1831 revised edition of the novel, she “bid [her] hideous progeny go forth and prosper.” Author and creator, medium and monster were thus linked around the question of life-giving and its legitimate means. But what were these means?

The novel devotes just a single paragraph to the creation scene, eliding any detailed description of “the instruments of life” employed, but suggestively indicating Frankenstein’s goal of “infus[ing] a spark of being” into the creature. Shelley’s 1831 Introduction returned to this scene, but it focused more on the author’s own act of creation during a dreary summer spent at Lake Geneva, where Shelley listened to ghost stories as well as reports of scientific advances, prior to having a waking dream that revealed to her the terrifying sight of the monster stirring to life.

The Introduction does add one other detail to the fictional act of creation, attributing it to “the working of some powerful engine.”

Furthermore, the author reports listening to conversations between Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley on “the nature of the principle of life,” paraphrasing or elaborating that “Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things.” Connecting the “spark of being” to galvanism, this would seem to be the source of the electrical interpretation of Frankensteinian creation.

However, it is important to note that the novel itself indicates that the young Frankenstein was obsessed with alchemical authors, and he later declares that “natural philosophy, and particularly chemistry, in the most comprehensive sense of the term, became nearly my sole occupation.” A recent article by Mary Fairclough argues convincingly that, for both Mary Shelley and the characters in her novel, electricity and chemistry were intimately entwined, and with them also questions of physiology.

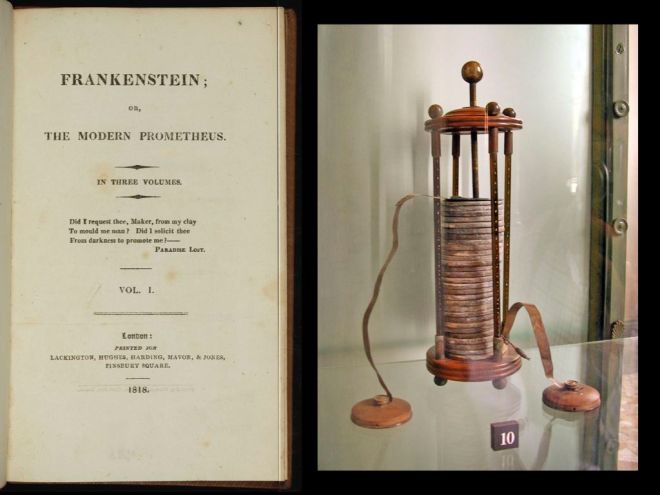

It is possible that the “powerful engine” envisioned by Shelley was a “battery” of “galvanic piles,” a device invented by Alessandro Volta to refute Galvani’s claim that he had discovered so-called “animal electricity.” The device, applied widely in early 19th-century chemistry, was alternately seen as demonstrating that chemical reactions produced electricity, or that electricity was responsible for producing said chemical reactions. In any case, life—and the physiological reactions of living and dead bodies to the operation of the galvanic pile—remained a crucial site of practical and theoretical concern around this intersection of chemistry and electricity.

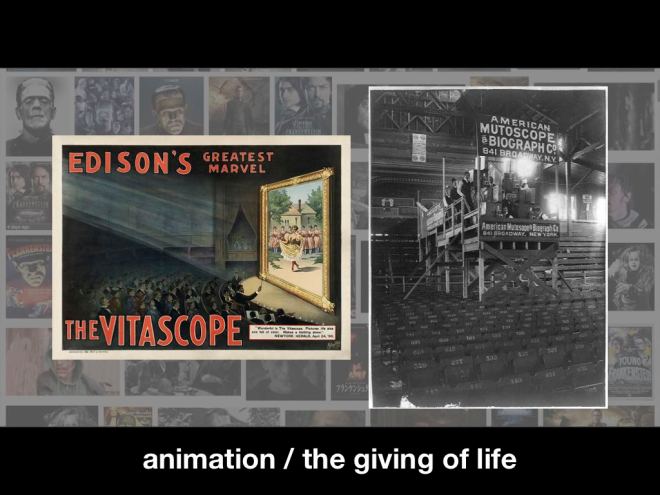

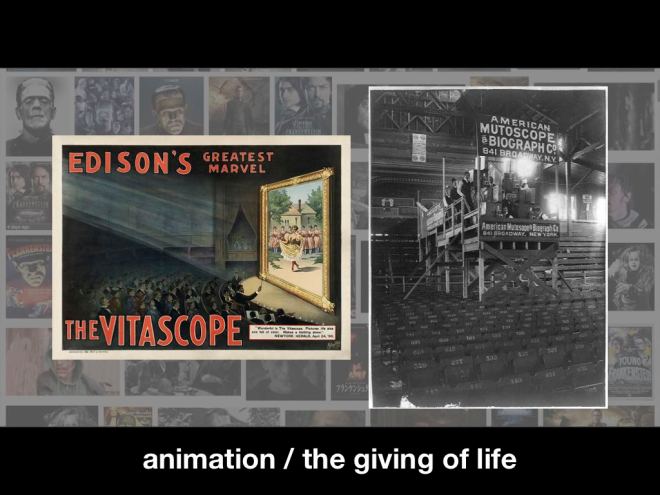

In the 20thcentury, the cinema would return again and again to Frankenstein, due in no small part to the fact that Shelley’s tale provided a seductive allegory for the life-giving powers of the medium of film itself. Like Frankenstein selecting parts from corpses and infusing life into a composite body, filmmakers utilized the technical means of film to (re)animate the “dead” (or photographically preserved) traces of living organisms (such as actors) into new visual narrative compositions. Discourses of animation, or the giving of life, were central to the early cinema’s understanding of itself, as is evidenced in the names of companies and devices such as Vitascope and Biograph. Given this overarching concern with the life-giving force of moving images, the Frankenstein tale provided an opportunity for reflecting on the changing conditions of animation, or the life of kinetic images. Seen in this light, a focus on electricity versus chemistry is less a matter of competing interpretations of Shelley’s narrative, and more a matter of cinema’s interpretation of its own media-historical situation at any given juncture.

Consider, for example, Thomas Edison’s Frankenstein from 1910, which stands between the early, image-technology oriented “cinema of attractions” and the coming narrative-oriented classical Hollywood style that would take shape around 1917. In 1910, the medium was in transition, torn between lowbrow technological spectacle and an uncertain reorientation along the lines of the respectable theater. Accordingly, advertising for the film emphasized both the “photographic marvel” of the creation sequence and the story’s origin in “Mrs. Shelley’s […] work of art.” The film aimed to be both visual and technological spectacle and narrative high culture. And this multiple address relates directly to the uncertain significance of “animation” at this historical juncture.

The creation sequence’s so-called “marvel” consists of footage of a burning mannequin projected in reverse—a bit of cinematic magic that, in the context of early film, served to exhibit cinematic technology by focusing attention on the filmic images themselves rather than the objects they depict. Frankenstein’s reactions here channel the scopophilic pleasure of a “primitive” viewer, for whom he stands in as a proxy. Importantly, “animation” here is a self-reflexive topos which links the monster’s creation with the term “animated photography,” still common in 1910 as a description of film in general. And the vaguely chemical or alchemical means of creation serve to link Frankenstein’s act to that of photochemical exposure and development processes—to the chemistry of film itself as the material basis of the images onscreen.

I have already noted how James Whale’s Frankenstein from 1931 changes course and places electricity at the center of creation, but this is again less about a specific reading of Shelley’s novel, and more about the cinema’s then-current means of animation. The film follows right on the heels of the massive transition from silent to sound cinema. And cinematic sound was widely associated with electricity, due to the revolution of vacuum-based amplification processes and the spread of radio in the 1920s. The noisy electrified lab where the monster is created gives objective form to the association, but it ironically gives birth to a mute, hyperphotographic monster—which is to say, a monster that didn’t quite live up to the electric promise of sound but instead reverted to the chemical base of filmic inscription. In any case, these media-historical aspects and associations faded from view as the Karloff monster was rendered an icon, or a visual cliché. After the sound transition faded from memory, only the narrative role of electricity as a life-giving force remained.

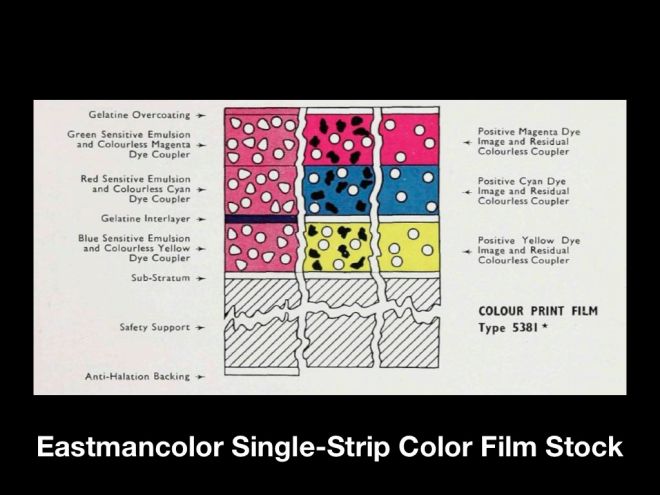

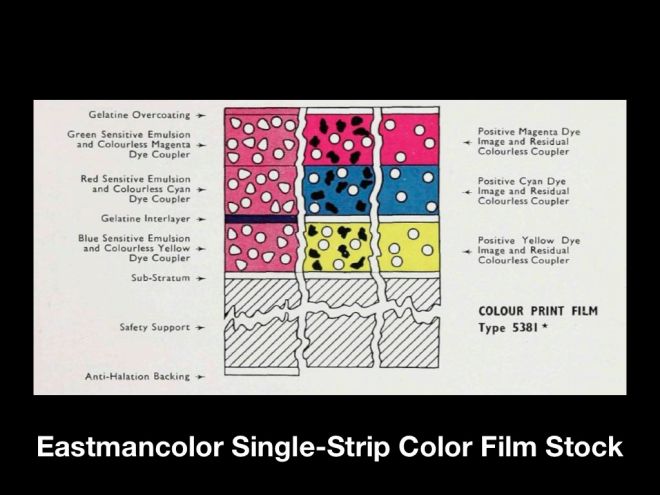

But there would be further opportunities for chemical reflection, most notably following the introduction of Eastmancolor, a cheaper alternative to the expensive and proprietary Technicolor process, which required studios to rent equipment and a technician to operate a special camera that recorded colors onto three separate strips of film. Eastmancolor, which recorded its images on a single strip of film, and thus allowed filmmakers to use standard black-and-white cameras for color shooting, was an innovation in terms both of chemistry and of economics. In terms of chemistry, the new color film superimposed three emulsion layers onto a single support, each responding to either blue, green, or red light. Each layer contains silver halide grains, gelatin as a binder, and what technicians at the time called a “color former,” a chemical that reacts with certain developing agents to produce a colored dye in the direct vicinity of exposed silver halide grains.

In terms of economics, this new process made color filmmaking available to lower budget productions, including B-movie exploitation films like I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (from 1957), which switched from black-and-white to color for the final, shocking scene. The result was a heightened “medium sensitivity” on the part of viewers, who were effectively confronted with the material difference between black-and-white and color film stocks—and made sensitive, on a visceral if not cognitive level, to the different sensitivities of their emulsions.

Also in 1957, the British Hammer Studios made creation itself a thoroughly chemical process in Curse of Frankenstein. Here, the camera positively dwells on lab equipment with bubbling liquids. Unlike the electric lab of Whale’s 1931 film, this is a thoroughly chemical lab—a perfect negative, in fact, to the darkroom lab in which the chemical processes of color film processing take place. Red, in particular, is a recurring color, associated with blood: the blood infused into the body of a monstrous corpse, and the blood spilled of innocent victims. But, ultimately, it would seem, a remark made by Jean-Luc Godard in reference to his own filmmaking rings true: Ne c’est pa du sang, c’est du rouge. It’s not blood, it’s red. Indeed, life is at stake, but the significance of red is unstable, wavering between the lifeblood of biology and the chemical emulsion of film’s own body.