Thinking about — or according to — Maurizio Lazzarato’s Videophilosophie.

Tag: experiment

Interactivity and the “Video Essay”

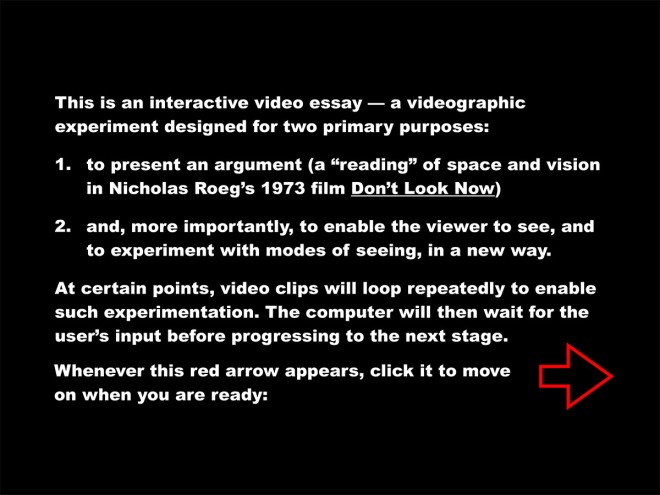

Recently, I posted a video essay exploring suture, space, and vision in a scene from Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973). Following my video essay hijab.key, which experimented with dirt-cheap DIY production (namely, using Apple’s Keynote presentation software instead of the much more expensive Adobe Premiere Pro or Final Cut Pro for video authoring), the more recent video, “Don’t Look Now: Paradoxes of Suture,” was also an experiment in using splitscreen techniques for deformative purposes, intended to allow the viewer to alternate between “close” (or focused) and “distant” (or scanning, scattered) viewing modes.

What I have begun to realize, however, is that these videos are pushing at the boundaries of what a “video essay” is or can be. And I think they are doing so in a way that goes beyond the more common dissatisfactions that many of us have with the term “video essay” — namely, the questionable implications of (and formal expectations invoked by) the term “essay,” which apparently fails to describe many videographic forms that are either more poetic in nature or that indeed try to do argumentative or scholarly work, but whose arguments are less linear or explicit than those of traditional essays. These are good reasons, I think, to prefer a term like “videographic criticism” (except that “criticism” is perhaps too narrow) or “videographic scholarship” over the more common “video essay.”

But these recent pieces raise issues that go beyond such concerns, I suggest. They challenge the “videographic” part of the equation as much as, or even more than, the “essayistic” part. Take my “Don’t Look Now” video, which as I stated is designed to give the viewer the opportunity to experiment with different ways or modes of looking. By dissecting a scene into its constituent shots and laying them out in a multiscreen format, I wanted to allow the viewer to approach the scene the way one looks at a page of comics; that is, the viewer is free to zoom into a particular panel (which in this case is a looping video clip) and become immersed in the spatiotemporal relations it describes, only then to zoom back out to regard a sequence, row, or page of such panels, before zooming back in to the next one, and so on. Thus, two segments in the recent video consist simply of fifteen looping shots, laid out side by side; they are intended to give the viewer time to experiment with this other, less linear mode of looking.

But the video format itself is linear, which raises problems for any such experiment. For example, how long should such a splitscreen configuration be allowed to run? Any answer will be arbitrary. What is the duration of a page of comics? The question is not nonsensical, as cartoonists can establish rhythms and pacings that will help to determine the psychological, structural, or empirical duration of the reading experience, but this will never be an absolute and determinate value, as it is of necessity in the medium of video. That is, the linear format of video forced me to make a decision about the length of these segments, and I chose, somewhat arbitrarily, to give the viewer first a brief (30 sec.) glance at the multiscreen composition, followed later (after a more explicitly argumentative section) by a longer look (2 min. at the end of the 9 minute video). But since the whole point was to enable a non-linear viewing experience (like the non-linear experience of reading comics), any decision involving such a linearization was bound to be unsatisfactory.

One viewer commented, for example:

“I think the theory is interesting but why the lengthy stretches of multi shot with audio? Irritating to the extent that they detract from your message.”

Two important aspects come together in this comment. For one thing, the video is seen as a vehicle for a message, an argument; in short, it is regarded as an “essay.” And since the essayistic impulse combines with the video medium to impose a linear form on something intended as a non-linear and less-than-argumentative experimental setup, it is all too understandable that the “lengthy stretches” were found “irritating” and beside the point. I responded:

“For me the theory [of suture] is less interesting than the reading/viewing technique enabled by the splitscreen. I wanted to give the viewer time to make his or her own connections/alternate readings. I realize that’s at odds with the linear course of an ‘essay,’ and the length of these sections is arbitrary. In the end I may try to switch to an interactive format that would allow the viewer to decide when to move on.”

It was dawning on me, in other words, that by transforming the Keynote presentation into a video essay (using screen recording software), I had indeed found an interesting alternative to expensive video authoring software (which might be particularly valuable for students and other people lacking in funding or institutional support); at the same time, however, I was unduly amputating the interactive affordances of the medium that I was working in. If I wanted to encourage a truly experimental form of vision, then I would need to take advantage of precisely these interactive capabilities.

Basically, a Keynote file (like a PowerPoint presentation) is already an interactive file. Usually the interactivity is restricted to the rudimentary “click-to-proceed-to-the-next-slide” variety, but more complex and interesting forms of interaction (or automation) can be programmed in as well. In this case, I set up the presentation in such a way as to time certain events (making the automatic move from one slide to another a more “cinematic” sequence, for example), while waiting for user input for others (for example, giving the user the time to experiment with the splitscreen setup for as long as they like before moving on). You can download the autoplaying Keynote file (124 MB) here (or by clicking on the icon below) to see for yourself.

Of course, only users of Apple computers will be able to view the Keynote file, which is a serious limitation; ideally, an interactive video essay (or whatever we decide to call it) will not only be platform agnostic but also accessible online. Interestingly, Keynote offers the option to export your slideshow to HTML. The export is a bit buggy (see “known bugs” below), but with some tinkering you can get some decent results. Click here to see a web-based version of the same interactive piece. (Again, however, note the “known bugs” below.)

In any case, this is just a first foray. Keynote is probably not the ultimate tool for this kind of work, and I am actively exploring alternatives at the moment. But it is interesting, to say the least, to test the limits of the software for the purposes of web authoring (hint: the limits are many, and there is constant need for workarounds). It might especially be of interest to those without any web design experience, or in cases where you want to quickly put together a prototype of an interactive “essay” — but ultimately, we will need to move on to more sophisticated tools and platforms.

I am interested, finally — and foremost — in getting some feedback on what is working and what’s not in this experiment. I am interested both in technical glitches and in suggestions for making the experience of interacting with the piece more effective and engaging. In addition to the Keynote file and the online version, you can also download the complete HTML package as a single .zip file (66 MB), which will likely run smoother on your machine and also allow you to dissect the HTML and Javascript if you’re so inclined.

However you access the piece, please leave a comment if you notice bugs or have any suggestions!

Known bugs, limitations, and workarounds:

- Keynote file only runs on Mac (workaround: access HTML version)

- Buggy browser support for HTML version:

- Horrible font rendering in Firefox (“Arial Black” rendered as serif font)

- Offline playback not supported in Google Chrome

- Best support on Apple Safari (Internet Explorer not tested)

- Haven’t yet found the sweet spot for video compression (loading times may be too long for smooth online playback)

Ancillary to Another Purpose

Michel Chion describes causal listening as a mode of attending to sounds in order to identify unique objects causing them; to identify classes of causes (e.g. human, mechanical, animal sources); or to at least ascribe to them a general etiological nature (e.g. “it sounds like something mechanical,” or “something digital,” etc.). “For lack of anything more specific, we identify indices, particularly temporal ones, that we try to draw upon to discern the nature of the cause” (Audio-Vision 27). Lacking any more concrete clues, we can, in this mode, trace the “causal history of a sound” even without knowing the sound’s cause.

As is already clear, there is a complex interplay between states of knowing and non-knowing in Chion’s description of listening modes, and this epistemological problematic is intimately tied to questions of visibility and invisibility. In other words, seeing images concomitant with sounds suggests to us causal relations, but these suggestions can be highly misleading – as they usually are in the case of the highly constructed soundscapes of filmic productions. This is why reduced listening – “the listening mode that focuses on the traits of the sound itself, independent of its cause and of its meaning” (29) – has often been associated with “acousmatic listening” (in which the putative causal relations are severed by listening blind, so to speak, i.e. without any accompanying images). As a form of phenomenological bracketing, acousmatic listening seeks to place us in a state of non-knowing with relation to causes and their visual cues, thus helping us to attend to “sound—verbal, played on an instrument, noises, or whatever—as itself the object […] instead of as a vehicle for something else” (29). In such a situation, we can focus on the sound’s “own qualities of timbre and texture, to its own personal vibration” (31) – or so it would seem.

Acousmatic listening is a path to reduced listening, perhaps, but only after an initial intensification of causal listening that occurs (that is, we try even harder to “see” the causes when we can’t simply look at them). In some respect, then, knowing the causes to begin with can actually help overcome this problem, allowing us to stop focusing on the question of causality so that we can more freely “explore what the sound is like in and of itself” (33).

I describe these complexities of Chion’s listening modes because they neatly summarize the complexities of my own experience of constructing, listening to, and experiencing a sound montage. This montage, which runs 2 minutes and 21 seconds in total, is constructed from found materials, all of which were collected on YouTube. The process of collection was guided by only very loose criteria – I was interested in finding sonic materials that are related in some way to changing human-technological relations. I thought of transitions from pre-industrial to industrial to digital environments and sought to find sounds that might evoke these (along with broader contrasts, real or imagined, between nature and culture, human and nonhuman, organic and technical).

The materials collected are: an amateur video of a “1953 VAC CASE tractor running a buzz saw” (http://youtu.be/wrGdgjoUJSg); an excerpt from the creation sequence in James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein (http://youtu.be/8H3dFh6GA-A); “Sounds of the 90’s – old computer and printer starting up,” which shows a desktop computer ca. 1993 booting Windows 95 (http://youtu.be/JpSfgusep7s); a full-album pirating of Brian Eno’s classic album Ambient 1 – Music for Airports from 1978, set against a static image of the album cover (http://youtu.be/5KGMo9yOaSU); “1 Hour of Ambient Sound From Forbidden Planet: The Great Krell Machine (1956 Mono)” (http://youtu.be/0nt7q5Rw-R8); and “Leslie S5T-R train horn & Doran-Cunningham 6-B Ship horn,” an amateur demonstration of these two industrial horns, installed in a car and blasted in an empty canyon (http://youtu.be/cjyUfV3W5zk).

The fact that these sound materials were culled from a video-sharing site had implications for the epistemological/phenomenological situation of listening. In the case of the tractor, the old computer, and the industrial horns, the amateur nature of the video emphasized a direct causal link; presumably, a viewer of the video “knows” exactly what is causing the sounds. The situation is more complicated in the other three sources. The Eno album is the only specifically musical source selected; and while it is recognizably “musical,” in that musical instruments are identifiable as causes of sounds, the ambient nature of the music is itself designed to problematize causal listening and to open the very notion of the sound object to include the chance sounds that accompany its audition. Nevertheless, finding the object on YouTube, where it is attributed to Eno as an album, and where the still video track of the album cover objectifies the sound as an encapsulated and specifically musical product, reinforces a different level of causal indexing. Similarly, the ambient sounds from Forbidden Planet might be extremely difficult to identify without the attribution and the still video image on YouTube; with them, a very general causal relation (it sounds like the rumble of a space ship, for example) is established – despite the fact that the real sound sources, the production processes involved in the studio film’s soundtrack, are obscured. The sounds from Frankenstein, from which all dialogue has been omitted, seem even more causally determinate: the video shows us lightning flashes and technical apparatuses emitting sounds. Especially in this case, but to varying degrees in all of them, knowing where these sounds come from makes it hard to put aside putative causal knowledge, to reduce the sounds phenomenally to their sonic textures, and not to slide farther into a form of listening that would seek to move beyond the “added value” of the sound/image relation and to locate the “real” sources of the sounds (as sound effects).

In putting together the sound montage, I was therefore concerned to blend the materials in such a way that would not only obscure these sources for an imagined listener, but that would open them up to a different sort of listening – a reduced listening that severed the indexical links articulating what I thought I knew or didn’t know about the sounds’ causes – for myself. For the reasons listed above, this was no easy task. Shuffling around the sounds still seemed like shuffling around the tractor, the thunder, the horns, etc. It proved helpful to randomly silence various tracks, fading them out and back in at a given point without any specific reason, sonically, focusing instead on the relations between the visual patterns described by the sounds on my computer screen. Especially the ambient sounds (Frankenstein, Forbidden Planet) proved easy to obscure, and the fact of severing their indexical ties to films and the themes they involved allowed for alternate hearings of the other sonic elements (horns, Windows 95 startup sound, etc.), which still retained their character of foreground objects but could be imagined in different settings, etc. (i.e. I was still caught in a form of causal listening, but I had begun imaginatively varying what the causes might be). For example, by varying the volume levels of these tracks, so that they became less distinct from one another, a clicking sound produced by turning on the old computer could be reimagined as starting a tape deck, especially as it preceded the commencement of the Eno music.

Getting past this level of reimagining causal relations, and moving on to a reduced form of listening, was no easy task, and I doubt that it can ever be achieved fully or in purified form. In any case, I began to discover the truth of Chion’s remark, that a prior knowledge of causal relations can actually help liberate the listener from causal listening; thus, the complications described above, stemming from the fact that I found my materials on a video-sharing site, actually helped me to get past the hyper-causal listening that accompanies a purely blind, acousmatic audition. I began hearing low electrical hums rather than identifiable causes, for example, but it remained difficult to get beyond an objectifying and visualizing form of hearing with respect to the buzz saw. The latter instrument was, however, opened up to alternative scenes: perhaps it was a construction crew on a street, and the spaceship was actually a subway beneath that street. Inchoate scenes began to open up as soon as a texture was discovered behind a cause. A dreamy, perhaps hallucinatory, possibly arthouse-style but maybe more ironic or even humorous, visual landscape lay just outside this increasingly material sonic envelope. It remained, therefore, to be seen just what could be heard in these sounds, especially when they were combined with alternate visual materials.

In the process of assembling the found-footage video montage – which I did not begin doing until I had finalized the soundtrack – I discovered an agency or set of agencies in these sounds; they directed my placement of video clips, suggesting that I pull them to the left, nudge them back a bit to the right, shift them elsewhere, or cut them out completely. A sort of dance ensued between the images and the sounds, imbuing both of them with new color, new meaning, and transformed causal and material relations. The final result, which I have titled “Ancillary to Another Purpose,” still embodies many of the thematic elements that I thought it might when I began constructing the soundtrack, but not at all in the same form I anticipated.

Finally, however the results of my experiment might be judged, I highly recommend this exercise – which I undertook in the context of Shambhavi Kaul’s class on “Editing for Film and Video” at Duke University – to anyone interested in gaining a better, more practical, and more embodied understanding of sound/image relations.