When this post goes online, I’ll be participating in a panel discussion (together with Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Sean O’Sullivan, and Ruth Page, and moderated by Jason Mittell) on the topic of “seriality and media transformations” at the workshop on Popular Seriality going on at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg at the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. Each of the participants has been asked to prepare a five-minute statement to set the stage and get things rolling. This is what I’ll be saying:

Seriality and Media Transformation

Shane Denson

The topic of this panel, seriality and media transformation, names a constellation of processes that, as I see it, are perhaps not essentially or necessarily linked, but which are nevertheless bound together as a matter of historical fact. I’m tempted to say that seriality and media transformation are “structurally coupled” under conditions of modernity. My thoughts on this topic follow from research I’ve been conducting with Ruth Mayer, where we’ve been looking at popular figures like Frankenstein’s monster, Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, or Batman – what we call serial figures, which proliferate across a range of media (but in a fragmented, plurimedial way, not by way of the more coherent, and more recent, transmediality that Henry Jenkins describes in terms of “world building”). In the context of this research, where we look at the way these figures jump from one medium to another, perpetually re-creating themselves in the milieu of a new medium, we are concerned with a nexus between seriality and mediality – a nexus where series are not just the contents of specific media (film serials, radio series, TV series, and the like), but where seriality is constituted as a higher-order medium, one in which the relations between and the transformations of first-order media (media as we usually think of them) are put on display, made visible, and negotiated. To make a big claim – because what else can you do in five minutes? – I would claim that it is the very hallmark of modernity to forge and reforge such a nexus of seriality and mediality; in other words, the articulation of seriality as a higher-order medium of media change is a central device for measuring, and indeed for constituting, the progression or forward march of a future-oriented modernity.

So we have to regard the media-historical function of the nexus: Because series unfold over time, they are subject to any changes that their carrier media may undergo. Not just passive receivers, though, series actively trace these transformations as they enact their own temporal unfoldings: the self-historicization by which series mark new installments against the old and in some cases stage qualitative transformations of their internal norms (as when Lost suddenly shifts from using flashbacks to flashforwards) – such processes of serial self-renewal and innovation can also serve as indexes of media change, and as the means for updating the idea of modernity in the process. Modernity itself is all about the update, and more often than not the update in question is all about innovations in media and technologies of mediation. So I’m suggesting that serial forms, which are inherently concerned with perpetually updating themselves, are the “natural” forms in which modernity would seek to stage itself.

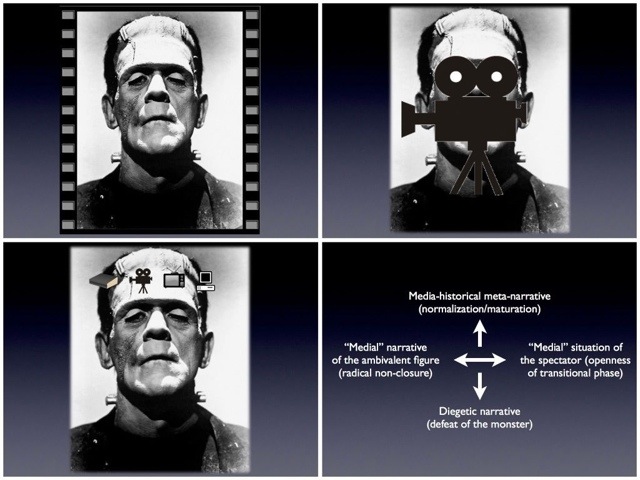

Of central importance here is the medial self-reflexivity that serial forms are in various respects capable of instantiating. I’ll just briefly consider the example of Frankenstein’s monster, conceived as a serial figure (or a figure of serialization). Originating in a highly self-reflexive novel about (among other things) the experiential deformations occasioned by industrialization, the monster was serially replicated on the increasingly mechanized theater stages of the nineteenth century, before it became subject, in 1910, of a highly self-reflexive film by the production company of Thomas Edison, the wizard of modern media-technological innovation himself. In the film, as in all the Frankenstein films that would follow in the course of the next century, animation is both a diegetic and a medial process. In 1910, the term “animated pictures” was still used to describe film in general and to distinguish it from the still pictures of photography, so the creation sequence instantiated a sort of “operational aesthetic” in which, against the background of the familiar figure, film could stage itself as a figure of modern media fascination. Importantly, this is at the outset of the cinema’s so-called transitional era, which would radically change the phenomenological and industrial functions of film. Nor is it an accident that the still iconic image of the monster, embodied by Boris Karloff, was established (in 1931) in the wake of the cinema’s sound transition. Robbed of speech, a mute icon served all the better to foreground the fact of sound and thus to stage the self-renewal of film, the updating of the medium’s modernity, against the background of the flat figure’s serialized history. The figure of the monster, which exists not in a series but as a series, which updates itself in color and widescreen formats, in 3-D and CGI, in comics, on TV, and in video games, increasingly becomes a medium itself: a second-order medium of media change, and of modernity as the trajectory of media-technical innovation, updating, and transformation.