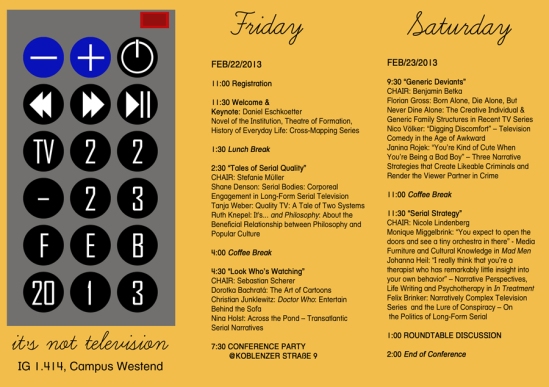

Below you’ll find the full text of the talk I delivered today at the “It’s Not Television” conference in Frankfurt. Unfortunately, I had to leave the conference early, so I didn’t have time to discuss the talk in any detail following the brief Q & A. I’m hoping, then, that some of those people who expressed an interest in discussing my ideas and proposals further might take the opportunity to comment here. And, of course, even if you weren’t there today, comments on this early-stage work are very welcome!

Serial Bodies: Corporeal Engagement in Long-Form Serial Television

Shane Denson

In this talk, I want to consider the possibility and the purpose of an “affective turn” in television studies. I’ll try to explain what such a “turn,” or refocusing of scholarly attention, might entail, and I’ll consider some of the grounds for making such a move.

First of all, the “affective turn” as I’m using the term describes developments going on in various disciplines, including philosophy and media and cultural theory, since about the 1990s. Following theorists such as Deleuze and Guattari, Steven Shaviro, and Brian Massumi, the “affect” in question here refers to a domain of pre-personal feelings, not subjective emotions but raw intensities that transpire below the threshold of consciousness, as functions and correlates of non-voluntary processes: for example, the not-quite-conscious sensations associated with visceral, proprioceptive, and endocrinological changes in one’s overall body-state. Thus, affects are diffuse material forces and sensations, whereas emotions are their more narrowly focused correlates; affects precede consciousness and envelop the mind, while emotions can be seen to involve the subjective “capture” of affect, the yoking of affect to consciousness, or the filtering and processing that takes place when pre-reflective affect becomes available to reflective conscious experience. Theory and criticism undertaken in the wake of an affective turn seek to uncover the material and cultural efficacy of affect prior to this filtering.

But why would television scholars want to make this turn towards a subterranean domain of pre-personal affect? Briefly, I want to propose that an affective turn would help to highlight the richly material parameters of the televisual experience, to focus attention on embodied interfaces and non-cognitive transfers, thus providing a counterpoint to the dominant celebration of cognitive effort in recent television studies. In other words, the context for an affect-oriented intervention is the tendency, widespread in popular and scholarly accounts alike of recent television, to intellectualize the medium, to focus on complex narrative structures in an effort to redeem TV from long-standing prejudices and stereotypes that cast the bulk of programming as culturally inferior trash produced for a passive, undiscriminating, and distracted mass audience. Foregrounding the emergence of a new televisual “quality,” many recent critical approaches have focused particularly on contemporary serial television’s demanding textual forms, which seek to engage viewers with complex puzzles and intricately orchestrated plot developments – thus breaking with the formulaic repetition characteristic of simple episodic programs and providing mental stimulation in exchange for viewers’ long-term investments of attention. As early as the 1980s, the advocacy group Viewers for Quality Television had defined “quality” in the following terms: “A quality series enlightens, enriches, challenges, involves and confronts. It dares to take risks, it’s honest and illuminating, it appeals to the intellect and touches the emotions. It requires concentration and attention, and it provokes thought.” In short, quality TV does what good literature is supposed to do, namely: to engage the viewer/reader and make him or her think. And popular criticism has continued to pursue this tack in the effort to make television respectable, e.g. by comparing newer series to the nineteenth century novel – The Wire, for example, has been called “a Balzac for our time”, thereby suggesting that this paradigmatically complex series distinguishes itself by a heady sort of appeal that rewards the sophisticated viewer. Steven Johnson has famously claimed that such complex television provides its viewers with what he calls a “cognitive workout.” And Jason Mittell, who has probably done more than any of these people to explore the mechanics of complexity, has noted the way complex series reward viewers who assume the role of “amateur narratologists.”

Clearly, the critical reappraisal of the medium and its implied viewer is not without foundation, as it speaks to very real changes in television programming in the wake of industrial, technological, and cultural shifts. Over the past ten years or so, there has indeed been an unprecedented flowering of programs that would seem to encourage active and intellectually engaged viewing. At the same time, though, graphic scenes of sex and violence proliferate across contemporary television series, including shows widely valued for their sophisticated cognitive demands. In particular, bodies are now routinely put on display, violated, tortured, dissected, and ripped apart in ways unimaginable on TV screens just a decade ago. I want to be clear that I don’t think this in any way invalidates theories and analyses that foreground the cognitive appeals of narratively complex TV. But this explosion of body images – including images of bodies exploding – does, I think, challenge such approaches to reconcile intellectual and more broadly affective and body-based appeals. By advocating an affective turn, a turn towards a diffuse, inarticulate field of pre-personal affect, I am not urging a turn away from consciousness or a regressive turn back to the view of an unrefined, unintellectual viewer. Instead, I am asking for more thought about how cognitive and affective appeals coexist today, and specifically about how they might be seen to work in tandem to maintain the momentum of contemporary television’s serial trajectories.

Seriality is the key word here: seriality is one of the things that’s illuminated particularly well by broadly cognitivist and narratological approaches, and it’s seriality, I think, that marks the real challenge for an affective turn in TV studies. Consider Brian Massumi’s definition of affect as “a suspension of action-reaction circuits and linear temporality in a sink of what might be called ‘passion,’ to distinguish it both from passivity and activity” (28). This conception, which Massumi associates with the thinking of Baruch Spinoza, accords also with Henri Bergson’s notion of affect as “that part or aspect of the inside of our bodies which mix with the image of external bodies” (Matter and Memory 60). And the Bergsonian image of the body as a “center of indetermination,” where affect is an intensity experienced in a state of “suspension,” outside of linear time and the empirical determinateness of forward-oriented action, corresponds to a major emphasis in film theory conducted in the wake of the affective turn – namely, a focus on privileged but fleeting moments, when narrative continuity breaks down and the images on the screen resonate materially, unthinkingly, or pre-reflectively with the viewer’s autoaffective sensations. Such moments figure prominently in what Linda Williams calls the “body genres” of melodrama, horror, and pornography – genres in which images on screen are mobilized to arouse pity, fear, or desire directly in the body of the viewer. In his now classic study, The Cinematic Body, Steven Shaviro explores extreme cases like the self-reflexive attunement between gory images of zombies dismembering and disgorging on-screen characters, on the one hand, and the embodied spectator affected viscerally by these images on the other. But these are moments of caesura, when narrative and discursive significance dissolves and gives way to an “abject” experience of material plenitude prior to its parceling out into subject-object roles and relations. These displaced or “utopic” moments, dilated experientially to allow for a poetic sort of tarrying alongside images, are of course already exceptional in narrative cinema, but they must seem even more clearly at odds with the vectors of serial continuation that pull television viewers from one episode to the next, engrossing them in a story-world and concerning them with the lives of its characters week after week, over the course of several seasons.

So if television studies is to make an affective turn, it will have to account for the medial differences between long-form serial television and closed-form film, and it will have to distinguish the role of affect in each. One place to start with this comparison might be the self-reflexive “operational aesthetic” that Jason Mittell, following Neil Harris’s work on P.T. Barnum, has attributed to contemporary serial television as one of its central mechanisms. For Mittell, the operational aesthetic is related to the cognitive operation of tracing and taking pleasure in the complexities of narrative twists. At stake is an enjoyment not only of the story told but also of the manner of its telling, and the operational aesthetic involves the viewer in what might be described as the recursive pleasure of recognizing a series’ own recognition of the complexity of its narration. But if television’s “narrative special effects,” as Mittell calls them, can be explained in terms of an operational aesthetic, it’s important to note that this mode of engagement has also been attributed to closed-form film to explain the appeal of special effects of the ordinary, primarily visual and non-narrative, sort. Tom Gunning has applied the term “operational aesthetic” to the body-gag spectacles of slapstick. In this view, Charlie Chaplin’s or Buster Keaton’s body gets implemented as a thing-like mechanism in a larger system of things, and the spectator takes pleasure in tracing the causal dynamics of the system, which is in a sense also the system of cinematic images itself; the cinema in turn reveals itself as a complex (Rube Goldberg-type) contraption for the transfer of material intensities from one body – Chaplin’s or Keaton’s – to another – my own, as the latter is affected physically and compelled to laugh. Similarly self-reflexive mechanisms are at work in sci-fi and horror films, where visual and visceral spectacles interrupt narrative flow and bedazzle or shock with an operational appeal to the body rather than the brain. Monumental explosions, monstrous sights flashed on the screen without warning, and show-stopping effects seek in part to bypass the brain and imprint themselves in the manner of the physiological Chockwirkung that Walter Benjamin took to be central to the filmic medium.

But is this corporeal sort of self-reflexivity, an operational aesthetic that arouses the body more than the brain, possible in long-form serial television? And, if so, can it be a central component of televisual seriality, a motor of serial development, or must it remain a mere side-show in a medium dependent upon the forward momentum of narrativity?

As I noted before, there is certainly no shortage of body spectacles on contemporary television, and they seem in many ways to function like the cinematic spectacles I’ve been describing. Procedural, or what might more properly be called operational, forensic shows likes CSI or Bones, for example, resemble science-fiction film in their showcasing of technological processes – processes that are anchored in diegetic techniques and technologies but that serve to foreground medial technologies of visualization. These displays serve, like the special effects of science-fiction film, more to impress the viewer than to advance the story. Significantly, such digressive forensic displays revolve around bodies and their imbrications with medial technologies: corpses are subjected to analytical methods that issue not in cognitive but in visual and media-technological spectacles, thus providing the spectator with an affectively potent – but narratively rather pointless – formula that gets repeated week after week. The technological probing of bodies onscreen thus speaks to and motivates a doubling of the viewing body’s own technological interface with the television screen – the material site of affective transfer, which is crucially at stake in these biotechnical displays. A show like Grey’s Anatomy similarly problematizes the integrity of bodies and sets them in relation to technologies, both medical and medial, in order to establish an affective circuit between bodies onscreen and off. Bodies in pain, bodies injured, impaled, injected, or incised, bones sawed, organs exposed and removed: all of these things have their place in a narrative, but they also maintain an excessive autonomy as images, establishing in this way a relay between an affective awareness of one’s own embodiment and an emotional engrossment in a melodramatic story.

And while these shows may tend toward the episodic or the formulaic, their employment of body spectacles might be seen to illuminate a range of contemporary television, including shows widely recognized as qualitatively complex. Premium cable shows like Nip/Tuck, Six Feet Under, Dexter, or Californication, for example, revolve around a variety of corporeal explorations. And a series like True Blood manages to combine all three of Linda Williams’s “body genres” into a hybrid mix of soft-porn, horror, and melodrama. The Walking Dead positively obsesses over its media-technological ability to generate graphic images of all states of bodily decay, thus offering a series of visual and visceral challenges to the viewer that run parallel to and punctuate the story’s unfolding. And even a starkly serialized and celebrated complex show like Breaking Bad activates these mechanisms when it visualizes a scene of bodily destruction like this one:

Here, there is a properly visual appeal, a showcasing of the image that involves the viewer by activating a sense of one’s own corporeal fragility – thus staging a deeply existential demonstration of physical vulnerability that culminates, and momentarily negates, all the narrative investment and development of character that has led up to this point. In other words, the affective force of this moment far exceeds its diegetic and medial temporality; with Massumi, we might say the image occasions “a suspension of action-reaction circuits and linear temporality in a sink of […] ‘passion’” or immersive involvement. But, I suggest, the scene demonstrates a synergistic or contrapuntal rather than strictly oppositional relation between narrative development and affective depth. The image of the exploded face retains a visual and affective singularity, an excess over and above the storyline in which it’s embedded, but its evocation of the viewer’s own delicate corporeality resonates as well with the series’ overall narrative focus on a protagonist whose body is under attack by cancer.

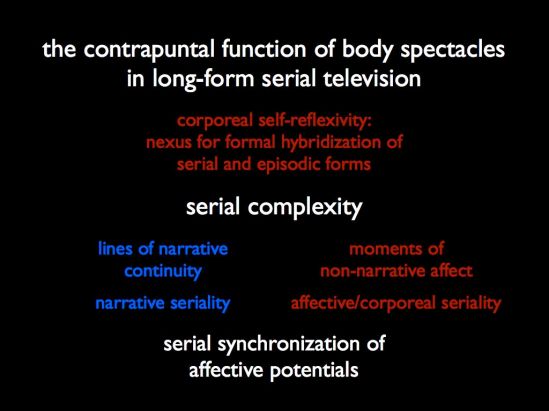

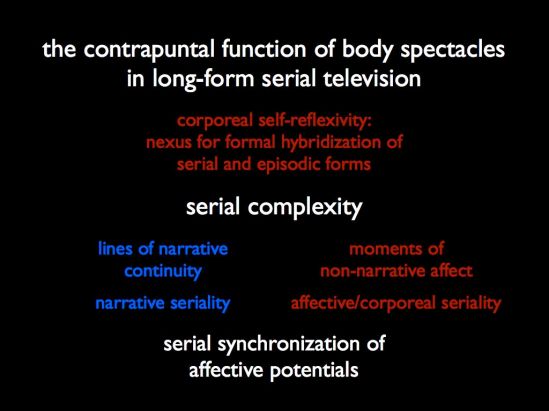

Finally, to generalize from these examples and wager a hypothesis about the contrapuntal function of such body spectacles in contemporary long-form serial television: I suggest that corporeal self-reflexivity, or the establishment of affective circuits by graphically opening up bodies for destructive, clinical, or sexual purposes, serves as a nexus for the formal hybridization of serial and episodic forms that Mittell makes central to his conception of narrative complexity. Not, of course, the nexus, but a nexus: in other words, a site where a certain sort of formal experimentation takes place, leading to an alternative form of “serially complex television” that activates an “operational aesthetic” for cognitive and corporeal means, in the process intensifying viewers’ investment in narrative developments by imbuing them with affective depth. I speak intentionally of “serial complexity” rather than “narrative complexity,” in order to account for the contrapuntal interplay between lines of narrative continuity on the one hand and moments of non-narrative affect on the other; by standing outside of series’ narrative temporalities, the latter moments punctuate continuity with discontinuity, but they also harbor the potential to establish an alternative seriality of their own, one that runs parallel to narrative development; this is an affective and corporeally registered seriality established through the repetition and variation of such poignant moments and images. Scenarios of the body-genre type serve then as fulcrum points for alternating between ongoing serial arcs and more episodically ritualistic engagements with affectively intense but narratively vacuous states of being: arousal by sexualized images, for example, or being moved to tears by highly melodramatic sequences (like the ritualized climaxes of Grey’s Anatomy, which employ music video techniques for a literally melodramatic presentation of bodily triumphs and defeats), or being shaken or disturbed by brutal violence and body horror (which can be occasioned by vampires, zombies, gladiators, serial-killers, or even health-care givers).

At stake, then, in television studies’ affective turn is the discovery of a broad, material site of serial complexity, of a nexus where shifts occur between serial and episodic forms or between repetition and variation, serially modulated through alternating appeals to cognitive effort and to bodily stimulation. By engineering self-reflexive feedback loops between onscreen body spectacles and the bodily sensitivities of offscreen viewers, contemporary series cement strong affective bonds between their viewers and the very form of complex seriality – with its shifting of gears and contrapuntal rhythms internalized at a deep, sub-cognitive level as the rhythms of one’s own body. Engagement with form thus becomes the embodiment of temporal vicissitudes that are as much those of the show as they are the flowing time of the spectator’s own affective life. At stake is a sort of serial synchronization of affective potentials, over and above (or perhaps deep below) the cognitive recognition of formal complexity. Such affective interfaces materially support and encourage mental engagements with narrative developments, but they do so by cultivating deep material resonances that, at the farthest extreme, institute a corporeal (perhaps endocrinological) need, a serially articulated demand for bodily replenishment or a weekly affective “fix.” The serialized probing of diegetic bodies is reflexively tied to a complex serialization of the viewer’s own body.